Where remarkable success is concerned, specialization matters. Warren Buffett started buying stocks when he was 11. Bill Gates started programming when he was 13. Tiger Woods was 2 when his father began teaching him to play golf.

Elite performers, in any field, tend to spend significantly more time on deliberate, focused practice than non-elite performers. Clearly, the earlier in life you start focusing on one thing (and by extension, the sooner you narrow your focus to one thing), the better.

Or not.

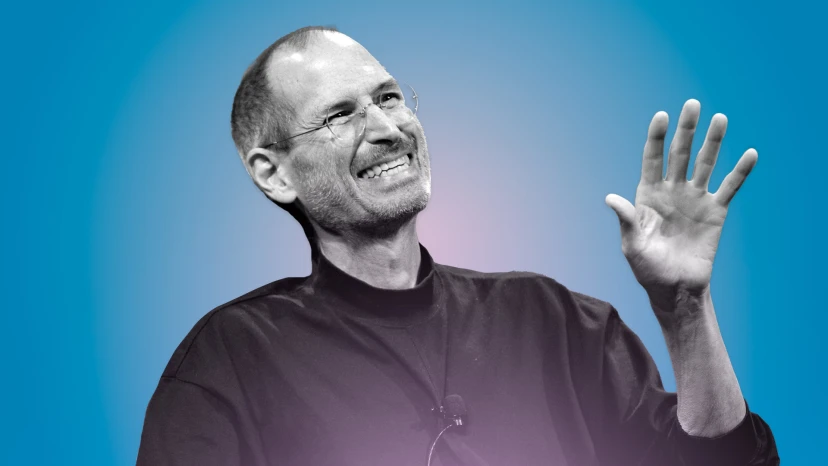

While Steve Jobs co-founded Apple when he was 21, before that he had attended and dropped out of college, traveled to India, and worked for Atari.

Hold that thought.

The “Positive Manifold”

Granted, we all know people who are extremely smart in one area and surprisingly not smart in others. (I’ve pushed the reset button on a ground-fault outlet for my vascular surgeon neighbor three times in the past six months; despite repeated explanations, he never understands why his toaster suddenly doesn’t work.)

But that’s more myth than reality. Smart people may not understand how things work outside their area of expertise, but that doesn’t mean they can’t learn. In fact, science says they’re more likely to be able to learn: Psychologists call it the “positive manifold,” the theory that different cognitive abilities tend to be correlated.

In simple terms, take one intelligence test and do well, and you’ll likely do well on others. But then there’s this: The positive manifold phenomenon shows that different abilities — not just intelligence, but abilities — tend to go together.

Best of all, knowledge and skills attained in one pursuit tend to be transferrable to other pursuits.

Transferrable Skills

In athletic terms, broader backgrounds tend to lead to later success. A study published in 2020 in the Journal of Sports Sciences found that athletes with more diverse athletic backgrounds appear to gain skills more quickly than those with less diverse athletic backgrounds over the same amount of practice time. Evidently, sampling various sports — and trying to improve in each — helps you better learn how to learn.

That’s also true for career success. As journalist David Epstein writes in his 2019 book Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World:

One study showed that early career specializers jumped out to an earnings lead after college, but that later specializers made up for the head start by finding work that better fit their skills and personalities.

Maybe that’s because generalists can take advantage of the positive manifold effect. Like Jobs and the calligraphy class he took in college; as he explained in his 2005 commencement address at Stanford:

I learned about serif and san serif typefaces, about varying the amount of space between different letter combinations, about what makes great typography great. It was beautiful, historical, artistically subtle in a way that science can’t capture, and I found it fascinating.

Jobs didn’t plan to go into the hand-lettered invitation business. But immersing himself in the art of calligraphy boosted his creative muscles and spilled over into other areas. As he’s quoted in the 2011 book I, Steve: Steve Jobs in His Own Words:

A lot of people in our industry haven’t had very diverse experiences. So they don’t have enough dots to connect and they end up with very linear solutions without a broad perspective on the problem.

The broader one’s understanding of the human experience, the better design we will have.

Fortunately, you can gain, and benefit, from new experiences — at any age.

Transferable Attributes

Take starting a business.

A study of 2.7 million startups found that the average age of the founder of the most successful tech startups is 45, that a 50-year-old startup founder is almost three times as likely to found a successful startup as a 25-year-old founder, and that a 60-year-old startup founder is at least three times more likely to found a successful startup than a 30-year-old startup founder.

And is nearly twice as likely to found a startup that winds up in the top 0.1 percent of all companies.

That’s the positive manifold in action: what you learn about work, and people, and life, and about yourself. Knowledge and skill in one area tends to be transferable to other areas. The more you know about different things, the more you can apply those things to other areas of your life.

Which could also make you happier. According to the authors of a study published in Nature Neuroscience, new and diverse experiences are linked to greater happiness. A study published in Journal of Consumer Research found that filling longer time periods with more varied activities makes the time feel more stimulating, which increases happiness. On the flip side, filling shorter time periods with varied activities makes the time feel less productive, which decreases happiness.

Which fits nicely into the positive manifold phenomenon. Spend a couple of hours doing a bunch of different stuff, and you probably won’t learn much. Spend a couple of hours focusing on building your skill and knowledge in a specific area, and you’ll definitely improve.

And feel happier as a result, because improving is always fun — and rewarding.

So go ahead. Learn a new language: You’ll improve your memory, increase your ability to focus, and gain broader cultural awareness. Learn to program: You’ll improve your logic, problem solving, and systems thinking skills. Learn to play an instrument: You’ll improve your memory, motor coordination, and pattern recognition skills.

You’ll better learn how to learn, which is knowledge you can apply to whatever interests you next.

Because success, for most of us, is a winding path with occasional crossroads, not a single destination. And so is happiness. And fulfillment.

And so is a life well lived, on your terms.

Stay ahead with the latest updates!

Join The Podium Media on WhatsApp for real-time news alerts, breaking stories, and exclusive content delivered straight to your phone. Don’t miss a headline — subscribe now!

Chat with Us on WhatsApp