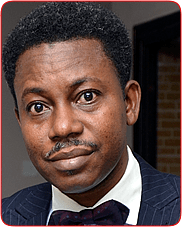

Each time shared or spent with former Minister of Works and Housing, Mr. Babatunde Raji Fashola, is almost equivalent to a session in any higher institution of learning. This is because quite often, the takeaways are both incalculable and worth the time given. In this encounter with Olawale Olaleye, Fashola, who is breaking off from active public service after 21 unbroken years, shares some of his untold stories, the usually misunderstood development issues, the obnoxious culture of owning negative statistics about Nigeria and projects into the foreseeable future. Excerpts:

It’s been a long time coming. From being Chief of Staff, governor, and later minister, you were in public service for about 21 unbroken years. Did you choose this break, or is it an accident you have to deal with?

Well, I don’t know what you mean by choosing a break. As a minister, I served at the pleasure of the president. And when the tenure of the president ends, the term of the minister automatically too is over.

But when you look at it, I think all the elements converged together: First, I had done 21 unbroken years in public service in a career I didn’t plan. It just happened overnight. 16th of August 2002, I resumed as Chief of Staff, from there I became governor, from there Minister and, the coincidence then was that I was now sixty years old.

So, if I had been a regular public officer, that was the year to go. It was also the year it turned 35 years after I left school. So, either way, by public service rule, it was just auspicious that my 21 years in service coincided with my 35 years out of school and also coincided with the 60th anniversary of my birth.

What are you currently doing with your time, which you seem to have plenty?

I have plenty of time to do one thing, which is to sleep, and I am getting about eight hours of sleep now, since August. I was never an early sleeper even when I was in active law practice, but since August 16, 2002, when I became a public servant, I was averaging three to four hours of sleep a day for the last 21 years.

That takes its toll on your body. I am sleeping a lot more and I am also learning to eat and enjoy food. Before now, food was just fuel. ‘Eat and move’. Of course, I also have time to plan around sports, exercise, and recreation, and also reintegrate myself back into my old societies, clubs, social events, and family, especially my immediate family.

There was a perception – true or false – that BRF the governor was different from BRF the Minister. Do you agree, and what are the distinguishing elements?

Clearly, being a governor and being a minister of the republic are two different responsibilities. On the one hand, a state like Lagos is only one out of 36, and when you become a minister you are responsible for all of the 36 states. So, it’s the responsibility of the state multiplied in 36 places. So, it’s a larger responsibility.

Secondly, at the state level, you are the chief executive. As minister, you are not the chief executive of the government. You are the chief executive officer of your ministry. Even then, the accounting officer of the ministry is your Permanent Secretary.

And then you are subject to some layers of consent or authorisation and there is a larger diversity of people to deal with, which you must respect, and must accommodate to be successful. So, I don’t know what those perceptions of the difference are but those are some of the dynamics of the difference between operation at the state and operation at the national level.

Talking about your days as governor, what did you think stood you out and earned you the sort of admiration you got from the people?

I don’t know what it is but the only thing I can say is that I took my job seriously and I worked with a team and many players in that team had their presence and character.

Whether it was our Commissioner for Finance or Budget, or Health, or Environment, Home Affairs and Culture or Sport or whatever, the Commissioners – each one of them – could have been governor and they had their presence.

But we worked as a team where we depended on each other and coordinated activities together. Perhaps, it was the presence of more leaders, rather than one leader that allowed us to reach many more hearts, if you like.

Taking into account how you came into office, you could pass for an accidental governor. How did you pick up so well and so fast, in the discharge of your duties?

I had been part of that government as Chief of Staff in the Governor’s Office. There were a lot of things I learned, closely working with a very hardworking governor at the time, Governor Tinubu, who also worked long hours at his work – worked us very hard.

So, that was a learning curve. I think it helped to make me the kind of governor I became because I was already in that space. And that is instructive for leadership preparation. The journey of leadership is perhaps similar to steps, rather than an elevator. You cannot go from zero to 60 floors within seconds. There are various steps by which you learn a lot of things.

Looking back and knowing that your principal then is very street-smart, would you say he probably had you in mind or had penciled you in as one of the likely persons to succeed him?

There was no such thing on the radar. There was nothing. I wasn’t actively involved in his politics. The person who should have succeeded him was Yemi Cardoso. Because we were all looking at a point and thinking that Yemi Cardoso was to run with him for a second term.

Your first appointment as Minister landed you three huge ministries – all rolled into one. This was a debate on its own and it also earned you the appellation: “Super Minister’’. But some people thought you were overloaded and as such, didn’t live up to expectations. Were you really overwhelmed?

When you look at, first of all, the fact that as a minister you are responsible for all 36 states, even if it was one ministry, that is enough work. But that wasn’t the problem with the perception of the public, because we didn’t have sufficient understanding of the mechanics of governance.

What was left in the power ministry? Traditionally, the ministry of Works and that of Housing had always been largely run together, so, there was nothing special in those two being together – traditionally from Alhaji Femi Okunnu’s time. So, the question to ask is: ‘What was the mandate of the Power Ministry?’

The ministry of power before 2013, when the privatisation was completed, would have been a real overload, because it had over 50 thousand staff before privatisation. All of what are now DisCos, GenCos, and TCN, were all assets and staff of the Ministry of Power.

But by 2015, when I became Minister of Power, the assets had been privatised since 2013, the staff strength of the ministry reduced from over 50,000 to less than 1000 – seven hundred and seventy-six.

More importantly, people perhaps didn’t bother to read what the Power Sector Reform Act provided for. It provided that the minister was essentially a policy adviser. He no longer has responsibility for the generation, transmission, or distribution of electricity.

The Ministry had become a Policy Ministry, and the Minister’s role was largely policy formulation because the agency that’s responsible for sanctioning and coordinating performance is the Regulator, the Nigerian Electricity Regulatory Commission (NERC). Just like the CBN of the Banking sector, NCC in the TELECOMS and National Broadcasting Corporation in the broadcast industry. It was essentially a policy Ministry.

That’s why some of the first things I did was to write an Energy Mix Policy for the country, to write a Mini-Grid Policy for the country, and to write a couple of other policies for the Energy Sector. So there wasn’t overwork.

Of course, it was my interest to interface with the stakeholders in the sector. That led to me visiting about 28 power plants around the country. I visited all eleven headquarters of the DisCos and some of their Regional operations.

I visited the National Control Centre in Osogbo. I had regular monthly meetings with all the operators in the industry in Nigeria, just to understand what the challenges were, because even if I was to make policy recommendations, I needed to know what the operators, for whom the policy was going to be made, wanted.

I can say this now, whatever people may say, one thing you could not take away was that, in those four years that I managed the ministry, there was progress and predictability about energy supply.

Breaking down the ministries each, how would you rate performance in the two others: Works and Housing?

There is a housing project in Abuja that started around the same time I was a minister. It’s a private sector project. As I speak to you today, they haven’t finished it. But in that period, a government that was supposed to be ‘inefficient’, completed housing estates in 35 states under the National Housing Programme. We completed housing projects through the Federal Housing Authority, some of which were commissioned before I left. We financed housing and built houses and completed some through the Federal Mortgage Bank.

In total, the national housing programme delivered about five thousand housing units or thereabouts. There were about six thousand housing units with the Federal Mortgage Bank, under the Ministerial Housing Programme. And I think to the extent that we delivered, it shows that the government could deliver housing at the federal level.

But my understanding was clear, that the bigger supply is going to be felt by what the state governments do. Because that’s where the control of land is. That’s where the need is greatest. Many of the states also delivered. And, if you want to see the full picture, you need to aggregate what the states and the federal government did to assess performance and impact. We are proud that some people got housing.

You served under a president that many Nigerians welcomed into office with staggering goodwill but left almost accursed. How do you feel when they talk about him in such derisive sense?

Since 1999, I have observed that we seem to love our presidents most after they leave office and just when they are coming in, but not while they are on the job. Those are things that I think should be the subject of research.

And if we have become displeased with them by the time that they are leaving office, the time has come for us to look in the mirror and ask ourselves: what do we want from them? Are we asking them to give us what is the irresponsibility? Are we assessing them fairly? And that is why I delivered a lecture titled: “What can the president do for me?”

Are you not worried that some members of this government that even the former president helped to install, are coming out to blame him for the woes of the country?

I think it has become traditionally African, perhaps, to find somebody to blame for a problem. And that’s the way I see it. So, I am not worried. I think that some members of our team also blamed the previous administration for some of the challenges that we faced. And, I remember that President Buhari then consistently used to have President Jonathan over, while some lower members of his own administration were blaming Jonathan’s administration.

It just tells you that the presidents don’t share those beliefs. They see leadership as a continuum, and so they get on with it.

It is not news that you are not serving in this government because you had actually served a notice. Not just that, you also said you didn’t need a title to serve. Are you, therefore, serving in any capacity – advisory or otherwise?

Of course, service to one’s country is an immense privilege, and it takes many forms. I am doing what I think is right and sensible to do to support my country and our government in the way that works best for me.

Public service is a different kettle of fish and politics is an Island on its own. While you are arguably a good administrator, some people say you have consciously stayed away from politics. Why is that?

What is consciously staying away from politics? When we were having the merger of the parties, the first meeting of governors, where the then merger was announced, I hosted it at Lagos House, Marina.

Also, I was head of strategy, appointed by the party in that merger process. I was head of manifesto drafting, later I was assigned responsibility for fundraising. So, if I am not politically active, what do you call these? Those are party appointments. I don’t cross lines. Having been elected governor, I can’t go and take the work of the chairman of the party, which is their responsibility.

Some of the things that some people consider as being politically active appear to me as interference or an overreaching of role. In other jurisdictions, you won’t see them going to take over the role of the party chairman. That’s not your job.

Anytime that my party has called me to come and do something, I have done it dutifully and happily. And, of course, some of the things that are described as politics, I don’t believe that they are politics.

So, I don’t lend my support to some of those things, because the undertaking of politics is a noble cause for societal improvement and development. Nobody can fairly say that I have not been politically active and supportive of the party.

Are you considering a return to practice as a lawyer, more so, being a Senior Advocate of Nigeria?

I am not considering anything now. But I haven’t ruled anything out. Right now, I am just resting and I am enjoying my rest. Going back to law practice means going back to work. I have to get back in the mood to want to work.

As I have told you, I have lived on three to four hours of sleep daily for the past 21 years. This is just how many months of resting. I haven’t even integrated myself into society; I haven’t done one year yet.

Let’s have some ‘Nigerian Public Discourse’. What informed the writing of this book and what is it all about?

It is about many things. But I think that you will find that it intends to stimulate intellectual rigour, to our discussionsabout developmental issues. I alluded to how some people think the Ministry of Power overburdened me.

A ministry of less than 1000 staff. That was mere policymaking. There was nothing left of it. It was a shell. But people didn’t understand it that way. And of course, people didn’t know that electricity had been privatised. So, they were still looking up to the federal government to give them electricity.

People don’t consciously see solar power as electricity. They are still looking for electricity on the grid. They don’t see generators as electricity and it’s important to take account of all of that and decide on which one we want to keep and which one we don’t want to keep.

Another objective is to invest in, perhaps, a generation younger than mine with a resolve to challenge some of the things that are said as if they were dogma, when in fact they have no intellectual, logical, or factual basis.

When you say ‘Nigerian public discourse’, how are the issues you are interrogating connected to the ordinary Nigerian?

Okay, so, let us look at the census for example. How many are we? Some people say we are 210 million, 230 million. It’s just whatever numbers you put out. That can’t be a basis to plan. If the census figures are wrong, planning will be wrong! If planning is wrong, implementation will be sub-optimal. If the implementation is sub-optimal, quality of life will be sub-optimal. That is how it affects people.

If two people are coming to my house, and I go and prepare for twenty, I have taken resources from another place to prepare for a non-event. That’s a waste! If twenty people are going to come, and I assume only that there are two, and twenty come, that’s a shortage.

This applies to the number of schools, hospital beds, classrooms, desks and chairs, energy per capita, water supply per capita, and how many people need water. So, we need to have near-accurate figures.

Then, we set ourselves impossible tasks by our hyperbole, exaggerations, negative exaggerations. Some say we have a 17 million housing deficit. Do you know what one million is? So, how many millions are we going to build, before we can have sufficient housing? That is not a rational way to address housing. It looks impossible. So, when a nation begins to set impossible tasks, it is depressing. It diminishes hope!

Then we say we are the poverty capital of the world, who says that? And we just own all of the negative statistics. That’s not the environment in which to raise people. We just have to come out and say, this thing doesn’t make sense. Not just because we want to say so, but because, as a matter of fact, it doesn’t make sense, compared to other jurisdictions.

Ultimately, what do you intend to achieve with the book at the end of the day?

The first is to promote intellectual rigour. If we think better, we will act better and will be in a better place. Also to destroy some of the hyperbole and myths that have gained almost legendary validation when there is no substance in them.

To debunk those things and hopefully inspire another generation after me to say, “No, this is not us. On the contrary, this is who we are. A better people, who can solve our problems because we know this is not factual”

This is your first book. Are there more in the works, including perhaps, a memoir?

Well, what I can promise now is that there will be a sequel to this. A memoir is a further ‘down the road’ thing.

At over 60, what does the future hold for you?

There are so many things that I am thinking of doing. One, of course, is mentoring people. I have been involved in a couple of local and international speaking engagements, and there is a possibility for more of that to happen.

I might teach if I find what interests me, but it would be around governance and public service, policy. Part of the future is to be healthy and also be moderate in my disposition now and enjoy my space away from public service as much as I can.

ThisDay