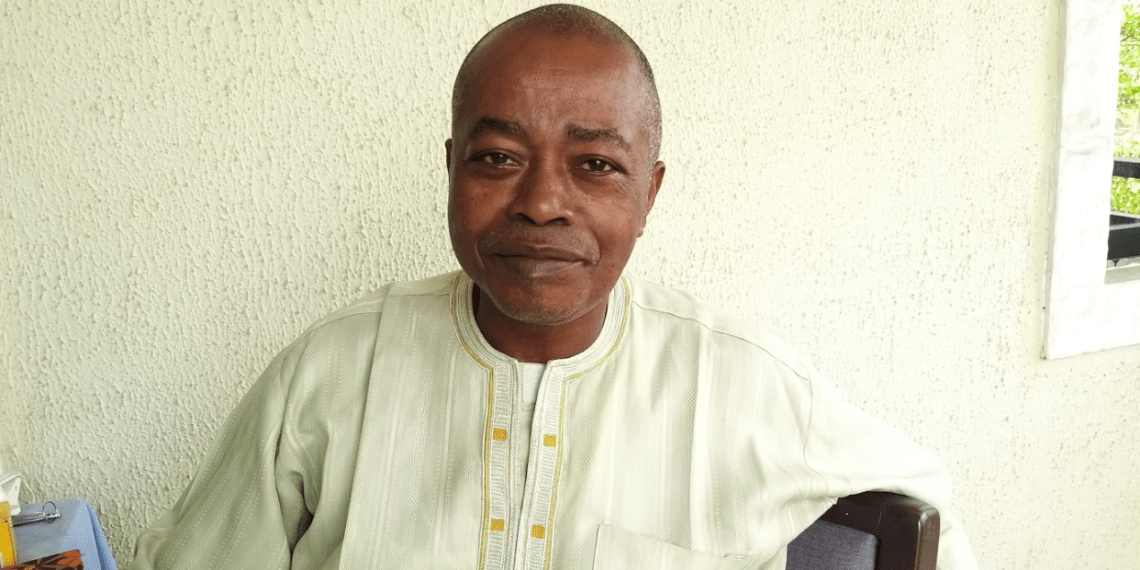

PT: How many years did you spend flying airplanes before you went into airline management?

OKON: I started, let’s say. 1976 because when I was flying for Mobil, it was corporate aviation, still a commercial flight. And then I did that until 1983. So, as you rise in the rank, you need to be given responsibilities. So I became a captain and within the year or the year after that, I became a fleet captain. A fleet Captain is a managerial position.

PT: It appears most Nigerian pilots have their roots in the defunct Nigeria Airways?

OKON: Yes, most of us came from Nigeria Airways. Say 90 per cent of us. There were a few others who came from outside, they trained themselves in the United States or in the UK and then came to join us.

PT: An aviation career wasn’t something common while you were growing up?

OKON: I didn’t start wanting to be a pilot, I wanted to be a captain in a ship. My uncle was a customs officer, he was on transfer from Calabar to Lagos. We went by boat. Somewhere along the journey, it was a three-day journey, the captain invited me as a little boy to the cockpit and I was taken in by the job he was doing as a captain in a ship and the powers that he had. Everybody respected him, and I said I was going to be a captain. So that was the beginning.

And then, during the Nigerian civil war, I was within the Biafra region and in the village. I lived in Calabar and then we moved to the village. First, we moved to Oron and then to the village. And the jet fighters would come and bomb, when they come, we will scamper to hide. That was a very humiliating experience. I said to myself, one day I’m going to be a fighter pilot. Nobody is going to be pushing me around anymore, I’m going to be the one in control of the situation. But I admired the work they were doing…

PT: Even with the pains of…

OKON: …You could see, one person had control, harassing everyone else and I didn’t like being harassed. Even if I was going to be involved in such a situation, I should be the one harassing others.

I thought that the person who flew the airplane at that time was an engineer. So I said I was going to be an aeronautical engineer. When I finished my last year in school, I applied to different universities abroad. I was given admission to Iowa Institute of Technology to study aeronautical engineering. During the war, my parents had no such money, the government was not in a position to send me abroad to go and study aeronautical engineering. So I applied to other institutions in Nigeria. I wrote to the Ministry of Transport, which was in charge of flying.

No, let’s go back a little bit. I was good at debating and I won a book, Careers in Nigeria. It was written by, I can’t remember clearly, E.C.N. Okang. That was my prize for winning the debate in St Patrick School, Calabar – first prize in a debate. So, in that book, I could see that the pilot was earning the highest salary.

So, I wrote to the Ministry of Transport that I wanted to be a pilot because that suited my ambition, with my experience in the war. And also the financial reward was better than anything else.

PT: What is thrilling about flying?

OKON: It is, oh! …You’ll get addicted to it.

There are some things that drive us. We want to seem to control things, to be in charge. You know adrenaline starts pumping and you get this feeling of power, you are put in charge of this airplane, you think you know how it flies. You have all these men behind you and you are to bring them up and down safely. So that drives you. You want to do it, and want to do it well.

PT: Do pilots get emotionally attached to a particular aircraft?

OKON: Your training takes that out of you. It doesn’t matter the aeroplane.

OKON: For me, that airplane was the Gulfstream II. It was a presidential jet at that time, I knew that airplane inside out. It had power. It was a small airplane, but the Gulfstream II could do things that the big jets couldn’t do.

PT: But that is a smaller plane?

OKON: Yes, but it could do things, and the way we used it. It was during the wars in southern Africa. The liberation of southern Africa. It started with Angola, Southern Rhodesia, and then Mozambique…

PT: So you flew that way too?

OKON: Yes, We were involved. You see Nigeria during the Murtala Mohammed regime and (Olusegun) Obasanjo regime, we were very aggressive. We had Africa as the centerpiece of our foreign policy. So, we had apartheid in South Africa, we had the Portuguese messing up Angola and Mozambique and Nigeria wanted them all free.

PT: But you were not flying for the military?

OKON: We were not. The military was not developed to that stage, so the government had an airplane, and a cabinet office flying unit. So I was attached to the flying unit of the government, even though I was paid by Nigeria Airways. The government had a fleet and a whole department.

The Gulfstream II was reliable. It would take us higher and faster than any other airplane. We were able to go to 43,000 feet – 43,000 feet was in the upper stratosphere. Most of the jets we’re operating, the commercial jets, maybe a one-hour flight, they’ll go to 27,000 feet, (and) 28,000 feet. But this one, we were able to go 41,000 feet, (and) 43,000 feet.

I have flown Obasanjo so many times. The Gulfstream II was more of a workhorse. It was used by the number two man, and to go on long missions. There is something the F28 couldn’t do. It did not have the range, and didn’t have the height to go into enemy territory. All of southern Africa was enemy territory, so we needed to sit far above any gunship or anything that would disturb us. So we’ll take off from Lagos and perch at 41,000 feet or 43,000 feet, depending on whether you are going east or west, and just stay there. You could afford not to talk to anybody until you were ready to go down. South Africa was definitely bad. Ian Smith in Southern Rhodesia had declared independence or unilateral decision of independence, this was enemy territory. Nigeria was funding all these freedom fighters, training them and we were taking our external affairs minister or somebody else there.

PT: Apart from dignitaries, were you flying cash down that way?

OKON: Of course, they were carrying cash.

PT: No arms?

OKON: No, it was too small to carry arms. If they did, they didn’t tell me.

PT: Apart from personal fulfillment and, let’s say, monetary gains…

OKON: … (Cuts in) Okay, let me tell you this since you’ve mentioned monetary fulfillment. You get well-paid as a pilot, but what people don’t know is that a pilot will gladly fly for free if you don’t pay him. If you want to starve a pilot, just tell him you can’t fly again. You’re grounded. He doesn’t want to hear the word grounded. A pilot loves it when he is flying. Sex is the nearest thing to the feeling you have when flying. You feel good, you feel fulfilled.

PT: Some people think the ADC Airlines’ licence was withdrawn after the 29 October 2006 crash near Abuja while others think it was about recapitalisation, that the airline was unable to recapitalise?

OKON: I had left the airline like 10 years before then. So I may not be able to speak directly. But after that, they did come back and they flew for a while. I left in 1998. The first one (the crash) was in 1996. I was (still) the CEO in 1996. I left in 1998.

PT: Did the first crash contribute to your leaving?

OKON: No! Because after that we built up the company again, and took it to great heights. The Pope (John Paul II) came (to Nigeria) in 1998. We carried the Pope. We were adjudged the best airline in Nigeria. And shortly after that I left.

PT: You were a shareholder in ADC?

OKON: I’m a major shareholder, even now.

PT: Were you pushed out? Was there some kind of power play?

OKON: Can I refuse to answer that question?

PT: Has the company been dissolved?

OKON: I cannot answer that because I have been out of the board.

PT: But you are a shareholder?

OKON: All I can say is that I haven’t got returns for a while. It’s in comatose, right now.

PT: After ADC, you started Fresh Airline. How far did it go?

OKON: We went very far. It was a very comfortable and quiet business for me – a retirement business for me. I had one customer, one airplane. But Fresh Airlines stopped operating when they complicated things. My one customer was the Central Bank of Nigeria. So I was carrying bullion for the Central Bank. It was quiet and simple. But when the government came in with multiple regulations, we could not fly, we couldn’t have an airline.

PT: After the limelight, you decide to…

OKON: …When I left ADC, I decided to go away from aviation completely. I was a major shareholder in ADC and I didn’t want to run anything in conflict with ADC. So I went away from aviation completely. I went into farming. In fact, I already had some farms.

PT: Before you went into Fresh Airline?

OKON: Yes, I wanted to do Agric-aviation. Special-purpose, mapping. There were special areas that were not attended to, and agricultural aviation was one of them.

But our government and regulations have been so one-track-minded. You see when Nigeria Airways was there, Nigeria Airways represented everything. If you think aviation, you’ll be thinking Nigeria Airways, as if the airline was aviation.

So when the government was drafting regulations for the industry, they had only Nigeria Airways in mind. They did not think that the aviation economy can come from several sectors.

When I left Nigeria Airways, for instance, I did not go into commercial aviation straight away. I was in the training arm of aviation. In fact, what does ADC stand for? ADC stands for Aviation Development Company. But a precursor to the Aviation Development Company was the Air Crew Development Centre. I used the Air Crew Development Centre, it was registered, to do some training. I train pilots, I run a flying club. I had a flying club in Kirikiri, Lagos. We went to Magbon. We did some training in Magbon. Magbon is on the west side of Lagos, and from there, I transitioned to Ibadan – Ibadan flying club. Took over that flying club and ran it for like a year. I left Nigeria Airways and did all that training before my partners joined me, before I got these other guys and then we said let’s call it Aviation Development Company. So not just aircrew development, we were going to do aviation development, cargo. We were going to do other aspects of aviation. So we started with cargo and training. We just expanded on the training I was doing before. We were so successful in the training that the governments of other countries came to me that I should come and train some pilots for their airline and we did that. We made a lot of money. We stayed there for about three years, made a lot of money. That was the initial capital we used to come into mainstream flying.

Mainstream flying is very expensive. To get the license is even very tedious. When the government came to make rules like an airline should have a minimum of two airplanes, now I think they say three or four – that is a stupid rule! If your aviation business requires one crop duster to do dusting, why should you have two?

(To be continued)

Premium Times