Basically, I grew up being an artist from childhood, in Uyo, which was then part of South Eastern State. (This was one of the states carved out in May 1967 from the old Eastern Region; the others being East Central State and Rivers State. South Eastern State was later renamed Cross River State, and on 23 September 1987, Akwa Ibom State was carved out of it, with Uyo as its capital).

I was born there to Sampson and Iquo Ekpuk.

Even before I could learn to read and write, I could represent what I saw around me, better than my peers.

Back in the day, you only went to school to learn how to write with paper; the first instrument of writing was the small blackboard (called slate). That was what children carried around.

In my own case, it was neither paper nor slate (rather), it was sand.

I think I can vaguely remember what my father had told me: that I used to draw all over the ground outside our house, on the sand, using a broomstick or my fingers. It was when I got to a primary school that I was bought a drawing book.

As it were, the sand was not just my playground, it was also my first canvas. I went crawling on my knees and drawing on the sand. (Giggles). So, you see, my knees used to be dark. Thankfully, not anymore. (Giggles).

This was just as the Nigeria-Biafra war was waning (circa 1969/70) and Nigeria was winning.

We lived on the main road…Oron Road… in Uyo. My dad had his tailoring shop in front, while we lived at the back.

Across the street from that road was a relief agency. Every day, the place was filled with people who lined up to collect food from the operatives. Every day. Soldiers also used to parade people who seemed to be prisoners of war on the street.

One of those days, I was drawing, as usual, on the sand. Then a soldier came over and asked me what I was drawing. I was said to have told him, ‘this is Gowon, this is Ojukwu.’

Apparently livid, the soldier was said to have asked me, who my father was. I took him to my father’s shop. This incident almost got my dad into trouble. The soldier called him a ‘sabo’ – shortened from a saboteur. Why? Because I (had the effrontery to draw Gowon, Nigeria’s Head of State, an archenemy, alongside Biafra’s Commander-in-Chief).

That was like drawing a line in the sand.

One of the soldiers saved my father that day. He told the other soldiers that he knew my dad and that he was a good man, and not a saboteur, and he should be left alone.

The first money I ever earned was also while drawing, as a child, and it also had to do with soldiers.

I was a child of war and so my drawings at the time revolved around soldiers.

This time, it was at Uyo Itam village (also in Akwa Ibom State) where my mum came from.

I was in my maternal grandfather’s compound.

Soldiers used to come to the house to consult him as he was a native healer. One day, a truckload of soldiers came to the compound, and I was drawing – on the sand – and they decided to throw me pennies.

I attended two primary schools.

The first was Offot Jubilee Primary School, Aka-Offot, Uyo. The other was John Kirk Memorial School, Etinan (named after Scottish surgeon Sir John Kirk who accompanied David Livingstone, fellow Scot, missionary and explorer, on most of his African expeditions).

It so happened that I went and lived in Etinan (about twenty-six kilometres, south of Uyo) with a married cousin, whom I admired so much. By the way, I used to be called esenowo in that Etinan. It meant stranger because I was a town boy who came and was just learning the village ways. For instance, when I went with my cousins to fetch water from the stream, I would carry my own bucket on the side of my head, and before getting home, the entire thing would have poured away. (Long laughter).

In 1972, I won an award for Etinan Division, and for John Kirk Memorial School, in the South Eastern State Festival of Arts and Craft. That was my first prize, for drawing, and I was in Primary Two. It was a certificate (of achievement).

My first tutor was a sign-writer from Anang, called Nna. H3 had his shop about three houses away from ours in Uyo. I loved what he did, and I always hung out with him. We were kindred spirits, so to say.

For that competition at Etinan, my mum handed me over to him for tutelage, as we were given topics to work on, to draw a fisherman, farmer (and the like).

I would say that my mother was (my earliest influencer). She was an artist in her own right, but she channelled hers into being a seamstress, designing clothes. So, really, when I began to show interest in art, she gave me all the encouragement I needed.

(Remarkably), because my skill was higher than anybody else’s, I was the one called upon by the biology and civic teachers to draw diagrams (used for instructions) on the board for the Primary Six class.

I was quite well-known as ‘the artist’.

For secondary education, I attended St Finbarr’s College (Akoka, Lagos, founded in 1956, by the legendary Rev Fr D. J. Slattery).

It so happened that my mother died, and my dad became a bachelor (all over again), and his youngest sibling, Ime Ekpuk, then living in Lagos, decided to bring my sister and I to live with him in Surulere. His wife was working at St Finbarr’s, and that was the (connection).

In terms of attainment in arts, nothing remarkable happened to me at St. Finbarr’s. I took fine arts in school certificate examination…(it was at least one subject) I could close my eyes and pass.

I went back home at the request of my dad.

I got admission into the School of Basic Studies in Awi, Akamkpa, Cross River State (established in 1977). My father sought to have better monitoring of my performance by his friend who was the school’s principal. I sense he felt that I had become more of a Lagos boy and had not paid too much attention to my education (giggles).

The School of Basic Studies was a preparatory school for entry into university. (Usually if one passed here, you got a direct entry into the university). It was through here that I passed my JAMB (Joint Admission Matriculation Board) examination and got admission in 1984 to study fine and applied arts at the University of Ife. I graduated in 1987, just as the university got a new name – Obafemi Awolowo University (in honour of one of its founding fathers, after his death on 9 May 1987).

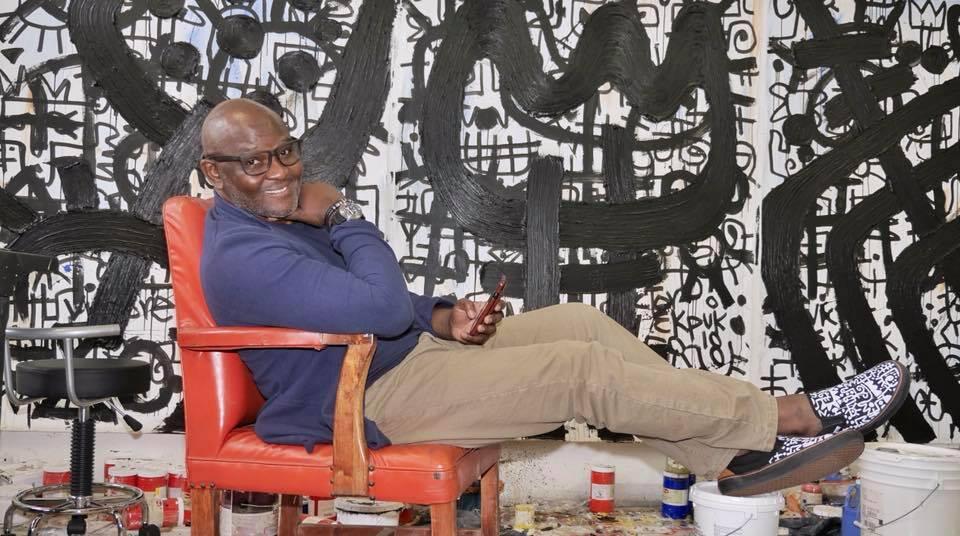

It was at Ife that I began to formulate my style. I do not have a name for that style. I am not one to be about names. I just know that is the vocabulary that I use (to express my artistic creativity).

But, it was from the tutelage at Ife that I found the need to explore traditional African art forms as a way to express myself, because that was how we were taught to specifically look: if it was good for Picasso, then it should be good for us.

(My teachers included) Profs Agbo Folarin (sculpture and drawing), Moyo Okediji, Rowland Abiodun (painting), Babatunde Lawal (graphic arts), and John Ojo (art history). Bolaji Campbell (now professor of African and African Diasporan Art at the Rhode Island School of Design, USA) was a graduate student around that time and he also taught me.

Prof Agbo Folarin, who has passed on, indeed opened my eyes to the possibilities of the power of lines, which is the basis of my work.

It was the first time (through his teaching) that I realised that I do not have to shade forms to express volume; that I could just thicken the lines rather than shade them.

He was also a kind man. If you had any problem and you went to him, he would spend time to help you, as if it was not a university where you were expected to go and find (ways around solving your problems).

Should I have gone to university to train with the skills I had? Yes. I believe that I got a lot from training in the university that I probably would not have got otherwise. Yes, I could draw. But the idea of conceptualising things and the idea of knowing that my artistic background, the cultural aesthetics for which I was born into was important as a form of identity, was instilled in me at the university. However, I did not think that I needed any extra training so I have not gone for any post-graduate training. If I wanted to have it as a backup to have a salaried teaching job, I could have considered it; because they (the academic institution) would ask for a second (or even third) degree). The only other education I had to do, after school was learning the business side of marketing my skills.

It was at Ife that, for the first time, I saw the work of Obiora Udechukwu. He did not teach me, but I saw a book of poems that he illustrated for Christopher Okigbo when I was already taken by the idea of drawing lines, and I was blown away by his lines.

Udechukwu used nsibidi in his works and his illustrations got my attention. I (knew that) this was from my place, and I began to look closely. (Nsibidi is an ancient system of graphic communication indigenous to the Ejagham peoples of southeastern Nigeria and southwestern Cameroon in the Cross River region. It is also used by neighbouring Ibibio, Efik, and Igbo peoples). I went back home and asked questions. I read books and research studies on the (art form).

So, yes, the illustration of Obiora Udechukwu pointed me in (my) direction. (It enabled me to) make sense of the tutelage at Ife. It was the (proverbial) light bulb….

I also became a book cover illustrator during my national youth service at the Africana First Publishers (an educational publishing firm) in Onitsha. I illustrated a whole volume of an English Language textbook, Intensive English, at Africana. And, at the weekends, I would travel to Enugu to hustle, and Fourth Dimension Publishers (owned by late Arthur Nwankwo) was one of the outfits I did book covers for. The late Nsikak Essien (master experimental artist) used to accommodate me in his house in Enugu.

It was while serving at Africana that I got employed (in 1989) as an illustrator by the Daily Times of Nigeria (DTN) when Dr Yemi Ogunbiyi was the managing director.

My friends from the university – Yomi Ola, Wole Lagunju and Kayode Tejumola – had already been employed at (DTN). At Daily Times, we were called ‘Ogunbiyi Boys’. (Dr Ogunbiyi too was once a lecturer in the Department of Dramatic Arts at Ife although his and Ekpuk’s paths did not cross there: he joined The Guardian Newspapers in 1983, a year before Ekpuk became a student at Ife).

When I initially started at Daily Times, cartooning was the thing. This caused me an identity crisis; having to decide exactly what I was supposed to be doing. While everyone else was about cartooning, I was more of an illustrator, even though I could do cartoons. I stuck to illustrations. I enjoyed doing a lot of caricatures of politicians. It was like payback time.

I was in the Daily Times for about eight years.

I fell in love with the woman who is now my wife (Marion Johnston, from California, USA) who was then working at the United States embassy, and when she was posted to the Republic of Benin, I had to join her there, because I did not want to be shuttling between the two countries. That was why I left Daily Times: it was love. (We have moved around a couple of places, including in the United States of America, where our son, Idaresit, was born in 1999 and where we are now based although my wife is currently working out of Kinsasha, the capital of the Democratic Republic of Congo).

My commissioned works include The Face, the largest stainless steel outdoor sculpture in the Republic of Bahrain, standing at about seventeen feet by fourteen feet in front of Bank ABC, in the Diplomatic Area, Kingdom of Bahrain. The bank’s CEO, Dr Khaled Kawan had gone to see the exhibition of another artist in New York, saw some of my works in the same space, and asked that I should be listed among those to be considered for the project. The rest, as they say, is history.

In terms of drawing, I was commissioned by Penguin Books (in 2018) to do the illustration for the reissue of Chinua Achebe’s books – Things Fall Apart, Arrow of God and No Longer At Ease – in commemoration of the 60th anniversary edition of the trilogy. I also did the cover of A Man of the People also by Achebe for Penguin.

I have a monograph of over four hundred pages, edited by Prof Toyin Falola, and with contributions from thirteen scholars, including Prof dele jegede (who was art editor of the Daily Times of Nigeria from 1974 to 1977, and had popular weekly cartoons in the equally vastly popular Sunday Times).

I am grateful that my parents did not discourage me from pursuing my passion for what I loved doing. It is important that I make that point. Every job that I have done has been art-related – illustrator, graphic artist, designer, sculpture…and it is because they encouraged me all the way. All the way.

I should add that it also came with a lot of work. It was not just that I had the talent, I have been putting a lot of work into everything. I have seen people who are super-talented but who were not able to put the (required) work to turn their talent into business to bring them (good) income).

I call my son, a ‘closet artist.’ On his own, he can draw, but he is not focused on making it a career. He is looking at making his own money elsewhere. He is free to follow his passion, just as I did, and made my name, Victor Ekpuk, a global brand.

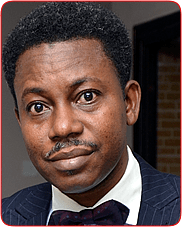

Photo: Courtesy of Victor Ekpuk

Update: The road where Ekpuk lived as a child has been corrected from Ikot Ekpene Road to Oron Road and “people lined up to collect food from soldiers” changed to “people lined up to collect food from operatives”

Credit: mytori.ng