Another week, another set of sobering economic numbers. Last Thursday, the Office for National Statistics published its latest quarterly estimate of the number of 16- to 24-year-olds who are so-called Neets – people not in education, employment or training. As usual, experts have warned that figures extracted from the UK’s flawed labour force survey should be taken with a pinch of salt. But there was still universal agreement about the huge issues the figures highlighted, and the hundreds of thousands of young people, 946,000, if the stats are to be believed, who are living on the UK’s social and economic edge.

The government has announced its latest review of all this, led by the New Labour veteran Alan Milburn, who will apparently focus on the relevance of disability and mental health. This week, moreover, Rachel Reeves is reportedly going to make the predicament of Neets one of the big themes of her budget. As ever, mood music is being provided by parts of the media that tend to specialise in the kind of condescension and generational loathing recently crystallised by a Daily Mail headline that might easily have been coughed out by ChatGPT: “Sicknote youths to dodge clampdown: Pledge to stop benefits for the workshy won’t include those with anxiety”.

The day the Neet figures came out, I had a half-hour conversation with Roman Dibden, the Manchester-based chief executive of a brilliant employment charity called Rise Up, which works with people aged between 16 and 30. What he talked about was filled with a sense of raw humanity. It began with his own life – he dropped out of school when he was 14, then spent the eight months that followed his 16th birthday unemployed, experiences that echo those of the young people he and his colleagues help. This year, the charity has assisted 120 people into work.

He often sees young people who have been unemployed for a lengthy period pivoting into what officialdom calls “economic inactivity” – moving on to sickness and disability benefits as either poor mental or physical health begin to dominate their lives – or withdrawing from the reach of the state altogether, a way of living that now defines about 44% of Neets. Inevitably, he talked about the long shadow of the Covid lockdowns, and the sense that their consequences for millions of young lives amount to a generational debt that has yet to be settled. “We’re talking about the Covid generation,” he told me. “A lot of it’s about anxiety, and confidence. And things that other people take for granted: the way that you walk into a room, the eye contact – they’ve not developed those things. And that’s a huge barrier.”

But so too, he said, is the sheer impossibility of navigating a benefits system and job market that are both full of trapdoors and dead ends. “Our young people have often just faced endless rejections,” he told me. “They’re disillusioned. And at the jobcentre it feels more like a monitoring exercise, so they feel under pressure. They’ll be applying for 150 or 200 jobs, to absolutely no avail – and they feel shit, frankly.” When they get to engage with employers, he said, the experience can be awful: “We get people telling us that with, say, certain parts of the banking industry, they’re doing interviews with an AI bot.”

Even if young people manage to make it into employment, they seem to run an ever-increasing chance of being tipped back out. About 170,000 jobs have been lost from UK company payrolls since last summer, and recently published analysis by the Guardian suggests that nearly half of those losses hit people under 25, presumably because of the age-old thinking summed up in the dreaded phrase, “last in, first out”. In that context, Reeves’s decision last year to increase employers’ national insurance contributions and thereby discourage hiring was an epic mistake.

After last year’s plan for a “youth guarantee” – which promises 18- to 21-year-olds in England access to an apprenticeship, training, education opportunities, or help to find a job – the idea is obligatory “work placements” for young people who have been on universal credit for 18 months or more without “earning or learning”. Outwardly, these should be undeniable steps in the right direction, but the latter comes with a grimly familiar bit of Whitehall boilerplate: “Those who do not take up the offer could face being stripped of their benefits.” Much the same logic ran through some of the abandoned welfare reforms that Reeves now says will be re-attempted – and clearly, the whip-crack of benefits “conditionality” will only make young lives more precarious and insecure, while barely scratching the surface of an issue that touches almost every area of policy.

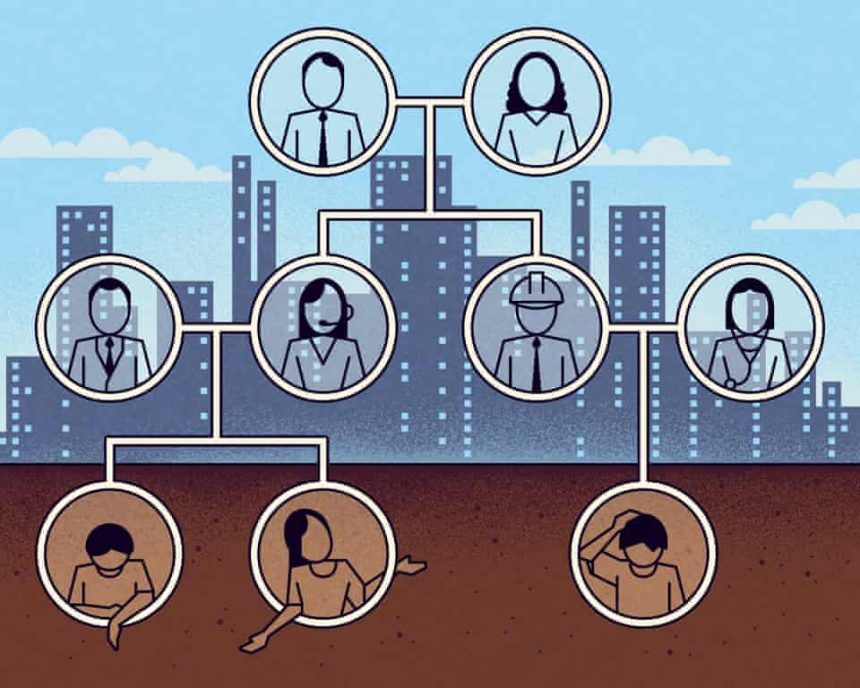

When I spoke to Xiaowei Xu and Louise Murphy, Neets experts at the Institute for Fiscal Studies and the Resolution Foundation, they both talked about problems that are systemic. Answers to the Neets emergency, for instance, are usually the responsibility of the Department for Work and Pensions. But by the time someone collides with the benefits system, it may be too late. Many of the problem’s roots lie in the schools and colleges overseen by education ministers who need to think much more radically: though the government has plans to boost vocational qualifications, our education system still operates on the basis that high-flying academic success is the only sure route to a secure career and a good life. Worse still, there are no clear ways back into education for young people who drop out, mostly because the further education colleges that ought to be at the heart of the modern economy are still feeling the effects of long years of insane underfunding and neglect.

And all the time, the job market becomes more and more impossible. New York magazine – along with other outlets –recently published an exhaustive piece about how AI seems to be drastically reducing companies’ dependence on the kind of entry-leveljobs that have always given people a means of starting their working lives. It quoted the founder of a data sharing platform who has stopped hiring junior coders: “There’s just no reason to deal with young employees”. And there was more evidence of what seems to be afoot: the online retail service Shopify, for instance, has told its managers that they must now justify hiring a human by first explaining why AI can’t do the relevant job.skip past newsletter promotion

Big tech, it seems, may soon be disrupting young people’s lives twice over – pulling them on to platforms that corrode the social skills necessary for a successful career, while automating the jobs that even work-ready teens and twentysomethings might once have walked into. Once again, that cruel prospect only highlights how deep this crisis goes, and two of the 21st century’s most vivid political questions. If our young people are anxious and depressed, might that be because there is a lot to be anxious and depressed about? And if their apparent fear and withdrawal sooner or later turns into uncontrollable fury, who will be surprised?

Stay ahead with the latest updates!

Join The Podium Media on WhatsApp for real-time news alerts, breaking stories, and exclusive content delivered straight to your phone. Don’t miss a headline — subscribe now!

Chat with Us on WhatsApp