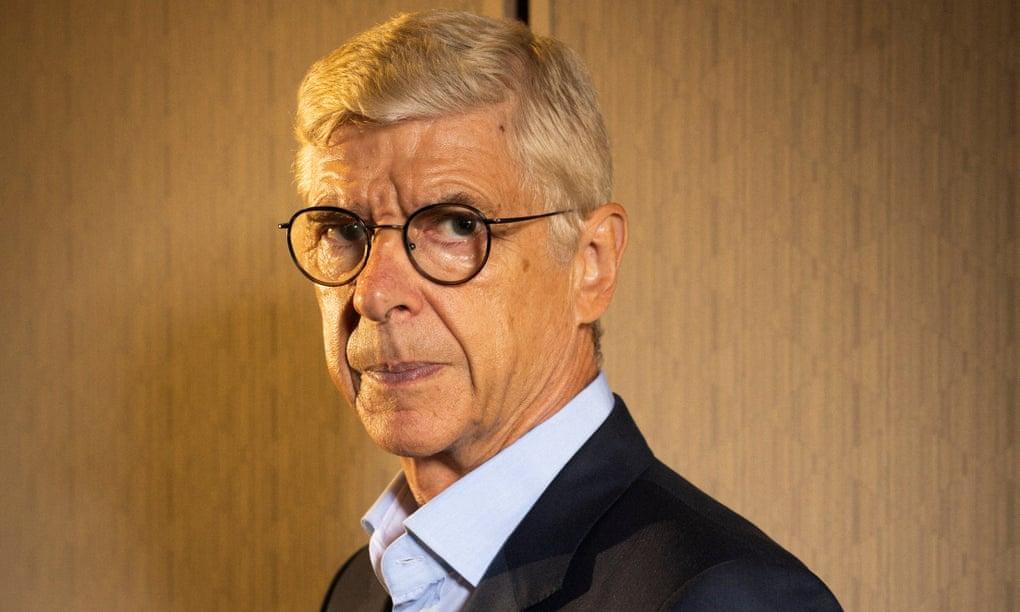

The former Arsenal manager has lived the best and worst of football. He discusses self-destruction, single-mindedness and the toll his job took on his life

rsène Wenger knows that his love for the beautiful game is actually an all-consuming addiction. For the 34 years he spent managing football teams – 22 of them at his beloved Arsenal – he was possessed by the need to win. Little else mattered. At times this devotion produced magnificent results. At others, self-destruction.

“Competition is something that eats slowly at your life and it makes of you a little monster,” he says, video calling from his office at Fifa’s Zurich headquarters, where he has worked since 2019. “That’s what I became, yes. I spent my whole life in top-level competition and it makes you slowly somebody who is psychologically obsessed and one-dimensional, someone who kicks out everything on the road that is not winning the next game.”

In a new documentary about his life and career, Arsène Wenger: Invincible, the 72-year-old declares: “The meaning of my life was football. Sometimes I’m afraid of that.”

His father, Alphonse, would never tell his son: ‘Well done!’, only: ‘You can do better’

“There are other important things in life – art, for example – that I didn’t explore at all,” he tells me, when I ask what’s so scary about this single-mindedness. “Maybe only geniuses can be successful in many multi-territorial things. I was not a genius; I had to dedicate my whole energy to one thing.”

But there’s no denying that it worked. When Wenger came to Arsenal in 1996, the impact was almost immediate. He won the Premier League title and FA Cup in his second season, becoming the first foreign manager to win the double, then did the same again a few years later. His crowning achievement was in 2003/04, however, when Arsenal became known as the Invincibles after winning the Premier League title without losing a single game. Even his greatest rival, Sir Alex Ferguson, had to give Wenger his due, commenting: “The achievement stands aside, it stands above everything else.” Arsenal still hold the record for the longest unbeaten run in league history, at 49 matches.

Two years before the Invincible season, Wenger had announced that he thought his team could do it – and been mocked for saying so. “If you don’t set high targets,” he says now, “you don’t push people to go as far as they could be.”

But there were obstacles off the pitch as well as on. Wenger was one of the first foreign managers in the league, and his arrival contributed to English football’s transformation from an inward-looking monoculture to the global game it is today. The press was sceptical – “Arsène who?” asked one infamous Evening Standard headline. Winning games turned that skepticism into hostility, “a mass of negativity because he was a foreign manager and he was doing things that are different,” Arsenal legend Ian Wright claims in the documentary. It climaxed with false reports of Wenger’s dismissal and rumours that a newspaper was set to print a highly compromising story about his private life. Wenger held an impromptu press conference on the steps outside Highbury, Arsenal’s stadium at the time, and said he was ready to refute the lies. No such story was ever published.

“I had enough maturity to deal with it,” says Wenger. “I think I have one quality, maybe, when I’m in adversity: I can concentrate on what is important and what is less important. At that stage, I felt surprised, but I felt: ‘Let’s do what I think I can do, which is to manage a football team.’ So I was not destabilised.”

There was a marked culture shift as players started drifting in from the continent, and individual performances were bolstered by revolutionary concepts such as a healthy diet and not following Ray Parlour’s lead by sinking 10 pints the night before a match. Wenger transformed Arsenal’s style of play from one of safety first to a more expressive, improvisational attacking game – which at its peak was christened “Wengerball”. And he brought calmness to the dressing room. Wright says Wenger was the first manager he had who didn’t indiscriminately “blast you down” at half-time.

“I felt always that the most important thing is that you get a good diagnosis of what’s going on,” Wenger says. “The hairdryer method [screaming at your players] is more to get your frustrations out – and it’s not very efficient. If you do that every week, people adapt to the behaviour of their manager. I thought it’s more important to be kind, master the situation and give an indication of what you should do.

“I thought: ‘What is the most efficient, not what is the most spectacular?’ I have a very passionate character; when I lose it, I lose it in a dangerous way. So I learned to control myself. Because you can make mistakes when you are out of control that you cannot repair.”

It bred fierce loyalty in his players; former Arsenal midfielder Emmanuel Petit says he would have climbed Everest without oxygen for him. Others have spoken about how Wenger was a father figure to them. “I believe that players have to know that you love them,” Wenger says. “The players must feel at the start that you can be demanding, but as well they must believe that, deeply, you want to help them.”

He led by example and prepared for games as if he himself was playing. He wouldn’t go out for 48 hours before a match (“Life in central London? I can watch that on television”), and knew only the triangle made by the training centre, stadium and his home in north London, where he lived with his wife, Annie Brosterhous, a former basketball player (from whom he separated in 2015) and daughter Léa.

His devotion to the game – not to mention his bespectacled, scholarly appearance and academic background – earned him the nickname Le Professeur. But, for all his reserve, Wenger was never the most gracious in defeat. He thinks this profound hatred of losing may have started in the village where he was raised – Duttlenheim, near the German border in Alsace, north-eastern France – at the local Catholic church.

“I was not the most patient child,” he says, remembering how he would be forced to kneel in front of the whole congregation after talking during services. Mass, being in Latin, was of little interest. “People went to my father’s pub and told him that I’d been kneeling in front of everybody again. That’s maybe where my hate for losing comes from: being humiliated.”

Wenger was born in 1949, the youngest of three children. His earliest memories – aside from ignominy – are of the football pitch and the village bistro his parents owned. It was used as a clubhouse for the local team; they’d get changed there then make their way to the match. Watching the men interact in the bar and studying their behaviour was “a great psychological experience for a boy” and kindled his lifelong fascination with the human psyche.

Wenger has always been very demanding of himself, for which he credits his father, Alphonse, who would never tell him: “Well done!”, only: “You can do better”.

“It was the style of education at the time,” says Wenger. “Today, when you educate your children, you give them more of the drive for quality of life. The generation after the war was more ‘work hard, don’t question that.”

“In a village,” he continues, “especially in a farmers’ village, you have a long-term view. You work hard, wait and maybe you will be rewarded. That’s what the farmer’s life is about. It gives you patience and investment in long-term work.”

Did any of his life’s achievements spur a “Well done!” from his father? “Never.” Not even the Invincibles? “No, it was not that kind of life. You don’t reinvent yourself at that age. He was of course very happy that things went well for me. But that was not his biggest quality, to say: ‘Well done!’ And maybe he was right, because one of the important things in life is to always try to be better.”

Wenger started playing football for the village team at 12; he would take his mass book and pray before and during the games, as it was the only way he felt they could win. Though a career in football was an unconventional path, his parents were happy he pursued his passion. “I was very independent, very young,” he says. “At 19 years of age, I had never gone out of my village. After that, I never came back to my village, and had a very international life.”

His professional playing career was short-lived and fairly unremarkable, taking in a handful of French clubs, including Strasbourg. By his early 30s he had secured a management diploma, had graduated from Strasbourg University with a degree in economics, and begun coaching the Strasbourg youth team. Managerial stints at Nancy and Monaco followed, before a brief spell in Japan at Nagoya Grampus Eight.

It was a chance meeting that led him to Arsenal. He went to watch a match at Highbury and at half-time shared a cigarette with Barbara Dein, wife of David, the club’s vice-chairman. She introduced the two men, they struck up an immediate rapport, and Wenger was appointed manager in 1996.

If the first half of Wenger’s reign as Arsenal manager was characterised by success, the second was more problematic. When Arsenal moved from Highbury (“my soul”) to the Emirates stadium (“my suffering”) in 2006, it left the club with a lot of debt and fewer resources to invest in the team. Arsenal endured a barren spell of nine years without a trophy. “Wenger Out” protests became depressingly frequent.

Did the constant calls for his sacking ever wear him down? “No, I am quite focused on what I have to do,” he says. “I always said to the players: ‘The judgment of people depends on your performances, so that means it’s something that you can change.’ In this kind of job the assessment of other people is always overboard; it’s too high or too low. You are a genius or you are Mr Nobody, and the truth is always in between.”

In March 2018 he was finally told it was over. He left in May as the club’s most successful ever manager, with three Premier League titles and seven FA Cups.

Wenger wonders now if he should have left sooner: identifying with one club so fully for such a long time was, he feels, a mistake. “I didn’t even consider …” – he pauses – “I had so many offers to go elsewhere, you know, and at the end of the day it turned against me.” But he never fell out of love with Arsenal. “I will support the club until the end of my life because I think I contributed a lot to what the club is today,” he says. “I suffered a lot. I sweat a lot for every stone that is in the stadium and I sacrificed the best years of my life to do that. So I won’t renege on that. I will support this club forever.”

He is now Fifa’s chief of global football development, where he is known for his controversial support for a biennial World Cup. He has not returned to Arsenal since leaving three years ago. Many fans (myself included) feel that is a great shame. Is there a chance he will return this year? “This season? I don’t know. Because I travel a lot, you know, and I have a very, very busy schedule. But at some stage, why not?” He could come and sit with us in the North Bank? “Yes, that’s the best place! That’s my favourite one.”

But he has other priorities. Such was Wenger’s relentless focus on Arsenal, he was unable to take care of the people around him as much as he should have, including Léa, who is now in her 20s. He is now trying to repair the damage. “That’s why I told you the competition eats you slowly because you’re less available to other people. Every passion is selfish.”

Does he still carry the guilt of that selfishness? “Yes,” he says. “Less now because you put things a little bit more into perspective. I think it was Mark Twain who said: ‘There are two important days in your life: the day you were born, and the day you know why.’ And I knew, always, why. For me, it was obvious that I was [meant to be ] in football, in the competition. But of course, people around me maybe suffered from that.”

If he had to do it all again, would he strike a different balance? “No,” he says. “I believe that when you have a dream in your life, you have to commit totally, completely. There are prices to pay … but there is no other way.”

Wenger described leaving Arsenal as like witnessing his own funeral, such was the intensity with which his life’s work was eulogised. But his enduring feeling is joy, not mourning.

“Yes, I’m happy and content,” he says. “I have some days when I’m less happy and some days when I’m happier… But if happiness is to lead the life you want to lead, then yes, I am happy.”

- Arsène Wenger: Invincible is in cinemas from 11 November and on Blu-ray, DVD and Digital on 22 November

The Guardian

Stay ahead with the latest updates!

Join The Podium Media on WhatsApp for real-time news alerts, breaking stories, and exclusive content delivered straight to your phone. Don’t miss a headline — subscribe now!

Chat with Us on WhatsApp