It’s strange how the mind plays tricks on you when someone you love departs this world.

About two weeks after Nna’s passing on Friday, 1 August 2025, Tonia and I were deep in one of those long conversations that so often led us back to him. The topic was an old Igbuzo cultural practice — one that, as is often the case, leaned unfairly against women. We had spoken to Nna about it a few years earlier, seeking his counsel as we always did when a matter touched both conscience and custom.

He had listened patiently, his fingers tracing the rim of his walking stick as he often did when thinking, his head lowered. Then, in that calm, reasoned voice that always seemed to come from a well deeper than his years, he said:

“Yes, you are right. It is unjust that a woman who dies within the stipulated mourning period, is deemed to have committed an abomination and would be cast away to the evil forest. But to change what is old, first understand why it was born. Find its roots, then begin the conversation. Reform that endures must begin with understanding. Yes, it is even made worse because a man in the same situation does not suffer the same faith as the woman”

That was Nna: a traditionalist with a reformer’s heart. A man grounded in heritage. Yet unafraid to prune its branches when they grew crooked. He could hold a mirror to our culture without breaking it.

So, on that day — two weeks after he was gone — when our discussion reached an impasse, I said to Tonia half-jokingly, “Let’s just put a Videocall to Nna and know what the state of play is.” As I reached for my phone, she gently took my hand and whispered, “Nna is no more.”

A silence followed. Heavy, final, unbelievable. And I said, quietly, “Indeed. He can’t take a call in the mortuary.”

That was when the full weight of loss settled in. For so long, his presence was our constant. Teacher, private philosopher, cultural encyclopaedia, compass in the fog. When I doubted if I wanted to accept to serve as the leader of my age group, Ogbor Midwest, it was to him I turned. And when I doubted about how far we must reform the age group culture, retooling it for 21st Century impact, it was to him I turned with my now ‘generic question’: will it be an alu or abomination in Igbuzo culture if we did this or that? His voice was always a phone call away, his wisdom, my cultural compass, always within reach.

I had thought that because he lived so long, nearly a century, I had been given enough time to prepare for his absence. I was wrong.

And yet, in another sense, I was right. He did prepare us. He left behind a wealth of lessons, proverbs, and silent examples that will outlive any number of phone calls. He trained our instincts to ask, “What would Nna have said or done under the circumstance ?” and in that question, his spirit continues to answer. That spirit, sometimes in silent and unspoken words, just a gaze or eye contact, would guide me and my siblings throughout the long elaborate planning process for his funeral. ‘What would Nna say or do?’ became our compass.

The last time I saw him in person, I spoke to him as a son to a father, but also as a father myself. I told him that I was trying — truly trying — to be for my two sons and grandson what he had been for me: a source of grounding, a moral centre, a quiet flame of wisdom in noisy times.

He sat with his head lowered, listening. After a moment, he lifted his face, looked at me steadily, and said just two words:

“Jisike nwam.”

Keep it up, my son. Keep trying.

Those words have become my inheritance. Not of gold or land, but of purpose.

Nna lived a life that stretched across generations. He was a bridge from the pre-independence era to the restless, global world we now inhabit. He carried tradition not as a burden, but as a torch, lighting our path with reason, humour, and grace. His was not just the crown of an Obi, but the wisdom of an elder who understood that power is service, and service is legacy.

As the Boys, Tonia and I remember him, we find ourselves still guided by his calm presence. We still try to debate as he taught us to: thoughtfully, respectfully, seeking truth, not victory. His voice may no longer sound across the compound, but it echoes in our conscience and our choices.

Yes, Nna — we will “keep it up.”

We will honour your lessons, preserve your humour, continue your conversations, and live by the compass you placed in our hands.

Thank you for your impact, your grace, and your endless patience.

Safe journey to our ancestors. Your Okpu Eze crown is eternal; your light undimmed.

— Egbolumani Nwa Abako & his Wife, Tonia, your grandsons, Tonna & Chidi, and your greatgrandson, Noah (your Akaeze)

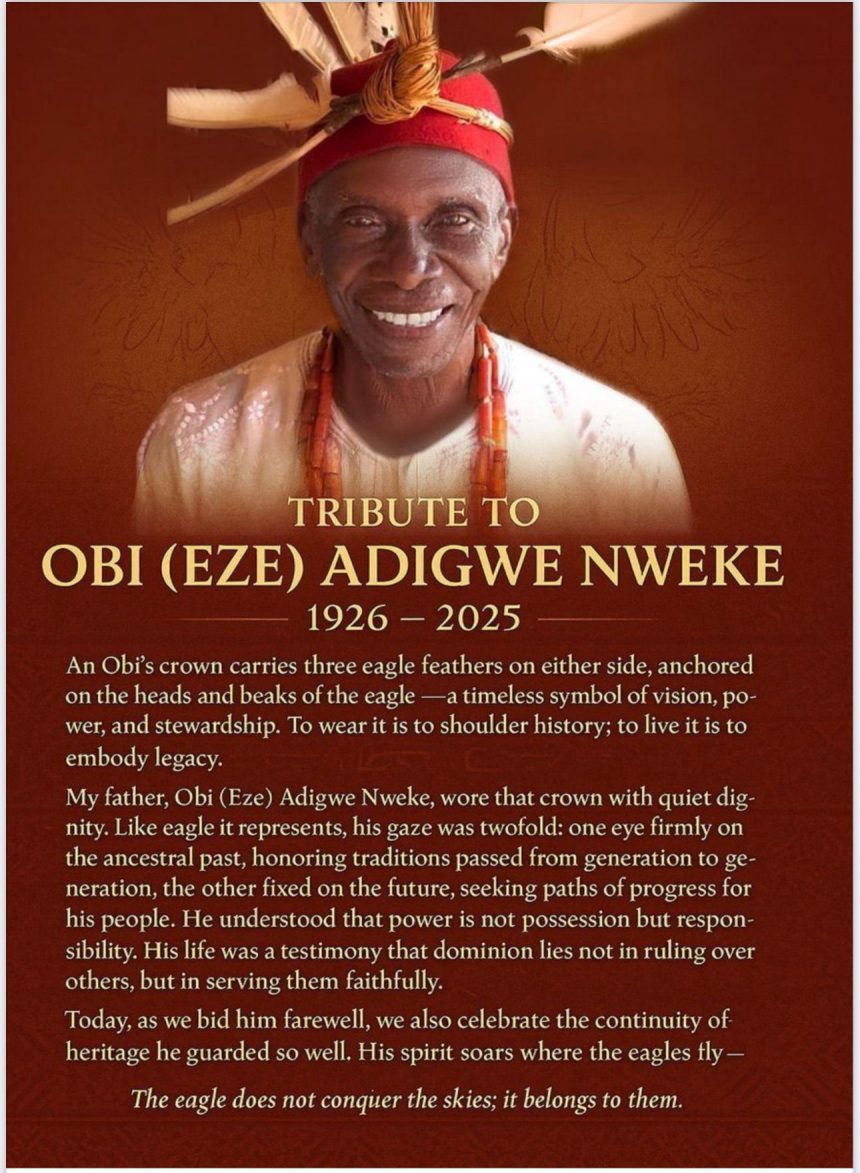

BIOGRAPHY OF OBI (EZE) ADIGWE “BLACKY” NWEKE

(1926 – 2025)

Born in 1926 in Isieke Umuekea Quarters of Igbuzo (Ibusa), Delta State, Adigwe Blacky Nweke entered the world as the first son of Obi (Eze) Ajudua Nweke, inheriting not just a lineage but a legacy of custodianship. He was the third child of seven; with two older sisters, two younger brothers, and two younger sisters, but from an early age, destiny placed on him the mantle of fatherhood. So deeply did he shoulder that role that his younger siblings, even in old age, called him “Nna” (Father) — not as metaphor, but as earned truth.

He grew up in the 1930s -1940s, a time when the winds of nationalism were slowly beginning to stir across Nigeria, yet the rhythms of traditional Enuani-Igbo life remained intact: communal labour, market days, ancestral reverence, and land-based wealth. In that world, children were legacy, land was identity, and lineage was immortality. As was customary for men of his time, he raised a large family. Not for vanity, but for continuity, productivity, and the dignity of ancestral responsibility.

Though he never passed through the gates of formal schooling, he was a man of rare wisdom, remembered by all who encountered him as a philosopher in native cloth a public intellectual in a pre-literate idiom. His Ezi-Obu or courtyard was his parliament; his words, his library; his life, his thesis. His life was the book he authored.

What he lacked in certificates, he supplied in clarity, ethics, and insight. He believed deeply in the power of education, and made it his life’s mission that his children — biological and fostered — would ascend to educational heights he lacked the opportunity for. Many who today bear degrees, careers, and names in faraway lands trace their first opportunity back to his insistence: Knowledge is the wealth that no fire can burn.

As Nigeria moved from the colonial 1940s into the heated politics of the 1950s and finally into Independence in 1960, men like Obi (Eze) Adigwe Nweke — traditional non-state custodians of order — played a quiet but essential role. At a time when the nationalist elite debated constitutions in Lagos and London, the Obis, Ndichie, and titled elders were negotiating peace at the Ogwa-Ukwu or village square, mediating land disputes, preventing factional violence, and ensuring that change did not burn down the moral architecture of society.

Long before the language of progressive governance was fashionable, Obi Adigwe Nweke practiced a lived social welfare model:

He fed widows from his harvest

Shared his vast landed assets with returning landless kinsmen

Fostered orphans without advertisement

Held land in trust for displaced families

Mediated disputes without accepting gifts

Considered the vulnerable a sacred obligation, not charity

Had he been a politician, history would likely have placed him among the Progressive Left, for he believed that society is only as strong as its weakest member. Yet he never had to seek office in a democratic gerontocracy system. He lived to become the oldest man, first in Isieke. He became the Diokpa of Isieke. Shortly afterwards faith and forefather blessed him with longevity, becoming the oldest living man in Umuekea and consequently was crowned the Diokpa of Umuekea. His office and authority required no ballot.

He rose through every traditional stage of merit and honour, holding all the prestigious titles of Igbuzo, culminating in the Eze title, exactly as his father and grandfather before him. When he wore the Okpu Eze, the scarlet crown with its eagle feathers and the carved double-headed eagle, it was not costume. It was covenant. For him, leadership was service, not spectacle; dominion meant duty, not dominance.

Steady as the iroko, he was the man his children took as hero, his relatives trusted, enemies respected, and strangers confided in. In times of dispute, his compound was neutral ground. In times of doubt, his voice was compass. In times of loss, his presence was anchor.

He lived 99 years. Not simply long, but weighty and meaningful. His life spanned the colonial era, the struggle for independence, the civil war, the oil boom, and the uncertain decades that followed. Yet through every season, he remained unbent in character, uncorrupted in judgment, and unshaken in identity.

Summary of Legacy

First son of royalty and custodian of ancestral lineage

A bridge between pre-colonial moral order and post-colonial social transition

A custodian of Igbuzo culture, tradition, and title hierarchy

A philosopher-king in the most indigenous sense

A believer in education as liberation

A practitioner of social justice before it was named

A father not only to his children, but to a community

A steward of land, memory, and peace

Proof that wisdom needs no classroom

Mentor and father-figure to siblings and community

Holder of all major Igbuzo traditional titles, crowned as Eze

Known as a philosopher, teacher, counsellor, and cultural patriot

Champion of education despite being self-taught

Practitioner of grassroots social welfare before the idea had a name

Peacemaker, land steward, and anchor of community order

Living bridge between pre-colonial moral order and modern Nigeria

Like the Okpu-Eze, the eagle with two heads that crowned him, he lived looking in two directions at once: backwards, to protect heritage; forward, to secure destiny.

And because of this, his story will not end. His story will continue in the lives, values, and names of those he raised, served, and loved. His story is deposited in his children of five generations at the time he joined his ancestors. May the earth rest lightly on him. May his memory be a blessing and his example enduring.

Stay ahead with the latest updates!

Join The Podium Media on WhatsApp for real-time news alerts, breaking stories, and exclusive content delivered straight to your phone. Don’t miss a headline — subscribe now!

Chat with Us on WhatsApp