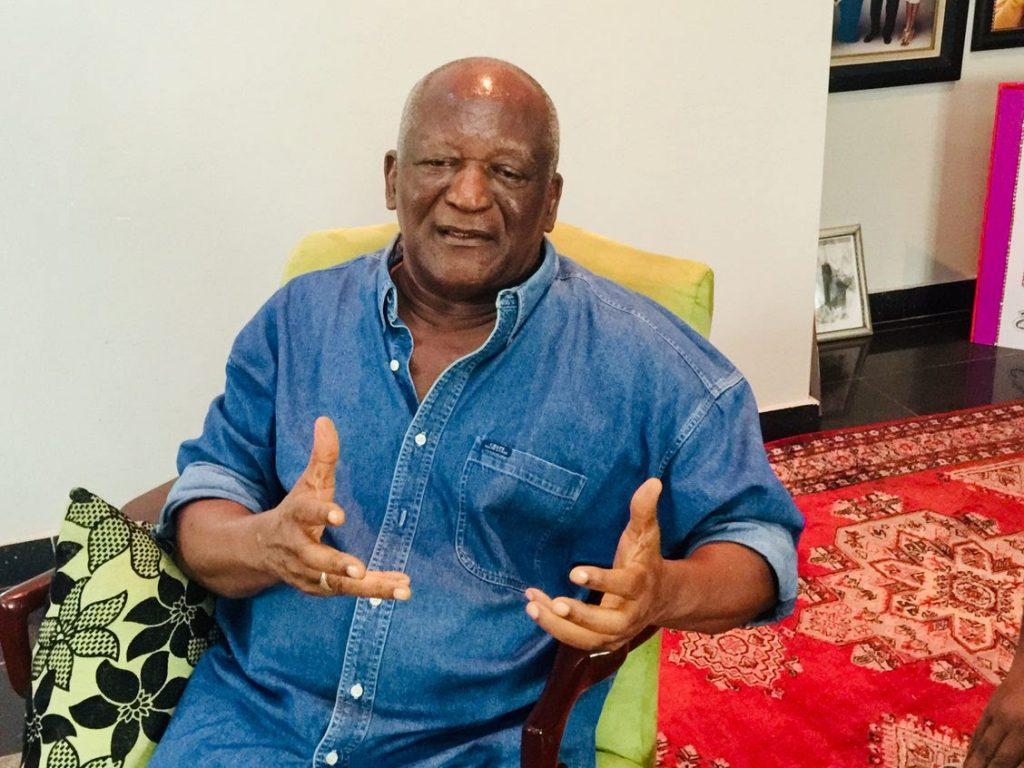

I grew up knowing that everybody called me Newton, or Chukwukadibia, for those who were closer. I was born on 1st January 1938 to Samuel and Ziporah Jibunoh of Akwukwu-Igbo (headquarters of Oshimili Local Government Area of Delta State, Nigeria). So, yes, I am Newton Chukwukadibia Jibunoh. But, you see, both my parents had died following a car accident when I was two or three years old, but I only knew when I was about seven. So that was my childhood situation, and I lived in different places with different relatives.

My dad’s younger brother, Abel Jibunoh, a farmer and politician – a member of the Western House of Assembly – was quite eager to have me educated, but he had his own family; he was a polygamist and worried that living with him without a mother to care for me, he gave me away, as was then the norm, to teachers and principals who in turn gave me the education I needed. This arrangement got me into Government College, Agbor, and Igbo-Ukwu Grammar School.

I travelled to Lagos in 1957/58 in an adventurous way. When I finished secondary school at Agbor and returned to Akwukwu-Igbo, my uncle wanted me to be a teacher. I did not mind but at the same time, it was not what I wanted, until something happened. My uncle acquired a new wife and got a new Raleigh bicycle for her. Before then, I ran a lot of errands with the old family bicycle. Like I could go from Akwukwu-Igbo to Agbor to pick up a carton of beer that she was selling.

I was always having a problem with the old bicycle, going on a long journey, so this particular day, a Sunday, they asked me to go to Agbor to pick up another carton of beer, so I waited for them to go to church. In those days, church services went on till about two p.m., and my journey by bicycle to Agbor used to take a maximum of two hours. But with a new bicycle, I had estimated that I would make it quicker, so I took it for the errand. When they came back from church, they found out that I had used the new bicycle, and some punishments were laid down for me, including twelve strokes of the cane. When that happened, I felt that the home was not the best place for me to be.

I think that I had thirteen shillings. So, I got on the road, found myself in Ibadan, the following day, and from there, I managed to take another vehicle to Lagos and went to a cousin of mine, who was shocked to see me because, of course, I did not tell him I was coming. I told him the story. However, with my Junior Cambridge certificate, with passes in mathematics, additional mathematics, and physics, it was easy for me to get a job at the Public Works Department (PWD). I also started evening classes at Yaba Higher College (later called Yaba College of Technology).

I started soon after to sit for scholarship examinations because those I worked with, people like Engr Olodude and Engr Atuanya, were sympathetic and nice to me, after knowing my parental misadventure. As a technical assistant, I helped out with drafting a lot of surveys and going on tours. Speaking of which, I was on the team which surveyed the construction of the River Niger Bridge. Halfway through, I headed the team.

The first scholarship examination I sat for was in 1960 but I did not measure up to the required cut-off point. How I knew was that my then boss, Engr Olodude, went with me to the Scholarship Board to find out why I was not on the list of the awardees. When the spreadsheet was shown to us, we found out that I scored sixty-two percent, but they started with those who scored eighty percent and when they got to sixty, they had taken the required number. People told me that if I had chosen the Soviet Union, I would have succeeded, but I wanted to go to the United Kingdom (UK). So, I had to study harder. When I sat for the examination in 1961, I recall that I scored seventy-eight percent. I was selected and I travelled to the UK.

I started with my initial diploma in building engineering at Hammersmith College, London. That took three years. I then went to Cranfield Institute of Technology for another year for the postgraduate diploma. Whilst doing this, I was also working. When I finished in 1964/65, I went to work full-time for a firm of construction engineers, Paskoki and Partners.

It was the era of the moon race between the Soviet Union and the United States of America. Cranfield Institute of Technology used to be an aeronautic engineering school but they were training some astronauts and they had an airstrip on the campus. That was where my interest in exploration started. I did everything to switch over but it was not possible. One, I did not have the requisite subjects which could lead me to aeronautics. Secondly, I could not change my scholarship, and thirdly, I had to return home because my scholarship bonded me to come back to work for a minimum of two years.

I researched what the whole space race was about and what it was likely to bring to the global community, especially in sciences. I decided that I wanted to be part of that era and if I was going to return to Nigeria, it was something I needed to take back with me. When I met some of the astronauts, I found out that they were no different from us; even though it did not stop me from wondering why it was they who had to explore and innovate. I realised that the difference was that we did not think outside the box nor bothered others about breaking barriers. That led me to think about what barriers I could break.

Len Crocker, an English guy, was my classmate and one of my closest friends. I had dropped out of an expedition through the Balkans with them because I could not raise the required funds. Len then broached the idea that both of us should drive through the Sahara Desert to Nigeria. That was how we started to find out what would make the journey possible. His money went into the preparations including contacting the Automobile Association to know the route and all that.

The pressure on him from his friends and associates at our workplace – we both worked at Paskoki – to not embark on such a journey mounted. His parents nailed the coffin, and he had to withdraw. I did not have anybody to tell, at least, not any parent. He tried to dissuade me. We read the story of two journalists who had died in their attempt to cross the desert; that it was madness to continue… I said to him: ‘Len if you are not coming, I am going.’ That was the day I made up my mind that nothing was going to stop me.

My ex-girlfriend, a Nigerian based in the UK, got to know me through friends and she wrote me an emotional letter stating that even though we were no longer in a relationship, she cared about what I did with my life and that this was not a good way to die. That letter touched me. Of course, I knew that I was going on an adventure that could take my life; at the same time, I prepared myself mentally, physically, and spiritually by saying to myself that I was going on an expedition and I may never come out of it but that I would have satisfied a good part of me that wanted to be an explorer; and was ready to risk my life for it.

So, on the 27th of December 1965, six or seven of my friends, including Len, gathered to say their goodbyes to me. I was given the wonderful book by Sir Francis Chichester who was the first to row the Atlantic on a boat and they all autographed it. It was while on the boat – I had driven to Dover so that I could put my car on the ferry to go across the channel = that I started reading the book, The Lonely Sea and the Lonely Sky. I found that Sir Francis went through the same psychological trauma as I did. He too was told that he was just going to kill himself, eaten by sharks and all that. But he also referred to most early explorers who did not make it. In other words, if you were embarking on an adventure like this, you should be ready to die first.

Leaving London was quite emotional. My friends gave the impression that they would never see me again, that I knew I was going to die and I was just looking for a nice way to commit suicide. I did not have anyone who believed that was not the case; in fact, some said maybe I would turn back somewhere. That was not an option: the thought never crossed my mind, not at all. What were the questions why was I that stubborn? Why should I ignore the love that my friends had for me?

When they were all hugging me, I broke down. Some of them did too. Len, for instance, cried openly.

Whilst preparing for the journey, Len and I had called the manufacturers of the car – which I had bought fairly used in Berlin, Germany, towards the end of my student life – in Wosberg, Germany, and told them about the adventure, and they were excited and asked that I should bring the car for free overhauling. I had a friend then in Berlin, Johnny Egbuonu, then a medical student who had also been one of Nigeria’s great football playmakers. Both of us had then driven the car after I bought it in Berlin back to London. So, the two of us went to Wosberg together. I think that it was Len who had spoken with them, or I did, and still had my English accent. When they saw me, they were shocked to see a black man.

They went into a long explanation that they did not carry out such a service any longer. I reminded them that we spoke only a couple of weeks back when they eagerly offered to do it. It was the racism of the 1960s that was at play. So, they agreed to do it but that I would pay for it, and this was not a cost that I had factored into my budget. Eventually, after a long argument and harassment, they gave me a discount for the overhauling and spares.

The day before I left Berlin, Johnny and I did not sleep. We spoke extensively about the adventure. He asked all sorts of questions. He just could not understand what I was trying to do. He too got emotional. We looked everywhere if there was a successful crossing of the Sahara in a car by anybody and we could not find any except those who tried and died in the process, and that worried Johnny, He went through my whole preparation and he was satisfied: he saw that I had taken care of everything, even how to obtain local currencies in those countries where I was going to pass through. I had the British pounds, United States dollars, and travellers’ cheques. But, those ones do not help you. Imagine coming to Asaba and going into a petrol station to fuel your car and you tell them you have pounds, dollars, or travellers’ cheques, they would think that you are mad. So, I had to make arrangements that, at every stage of my entering or leaving a country, to make me get their local currencies to deal with such issues.

On the day I left Berlin, Johnny rode with me for about twenty kilometres till he said I should stop. He got down and tried to hide his face as he was crying. He waved at me, and I tried to go away as fast as I could. Looking into the mirror, I saw him standing there crying. The issue of security was also an important one. Security in terms of protecting myself. But one must not be seen with any ammunition or arms or one would be in trouble. Not even a knife. It was not until I got to Morocco that I bought a poisonous knife.

Talking about Morocco, when I got to Ben Abis, I was told that they were no longer allowing the crossing of the desert. That, when the French legion troops were there, they would collect some money from one – I cannot remember how much now – and that if one was successful at the other end, the money would be handed back. But, if anything happened, they came to rescue one. They said that this practice had been stopped because the French took away all their helicopters and equipment, so they were no longer allowing people to cross the desert on their own unless in a convoy. I said that I would wait to go with the convoy. But they said that the last convoy was many weeks back.

So, they kept me there for six days. I was pleading with them. They even offered to buy my car and I could go to the next airport and fly to Nigeria. I refused. The commandant of the gendarmes was angry; that they were trying to save my life and I was still stubborn. Anyway, you know that when you have stayed at an army checkpoint, you would make friends with some of them. One of them advised that I go to the house of the commandant, that in the presence of his family, he might change his position. So, he was shocked when I appeared at his house at about seven or eight, one night, and I told him I was running out of food and money and that the option of selling my car was not on the table at all because I needed to cross the desert.

Fortunately, as some of the soldiers had told me, the family joined as they all felt sorry for me; the wife said something to him and he said, okay if I came with the money, he would give me a death warrant to sign. He then told the soldiers who took me to his house to prepare a death warrant and once I signed, I could proceed. So, I went back with the soldiers, and the following morning, the warrant was drafted and I signed. I was given a copy and I was allowed to go. That was a wonderful experience. In Switzerland, I found out that I could buy beautiful hand grenades made in the shape of eggs. I bought four. I had that feeling that if you wanted to kill me, I would kill you first or do some damage to you.

I used one in the desert when I was being threatened by a hungry-looking animal that I later found out was the Desert Bull, whilst trying to make my dinner. I had stopped driving that day. It just appeared from nowhere. I removed the pin from one and threw it at him when it made a move as if it were going to attack me. The thing just somersaulted and died. I cut off the head. I kept it as a memento, and it is still preserved.

The second time: it so happened that I could not get to sleep, and I started hearing voices, songs, conversations, and all sorts of things. I came out of my car and shouted: Who is there? But what I was hearing was in my head, but I did not know then because my head was already twisted. So, I had to throw the grenade in the direction where the voices were coming from. And, you know, immediately after that, everything went quiet. So, I assured myself that I must have destroyed whoever they were. I managed to catch a few hours of sleep. When I woke in the morning, I went to the spot where I had thrown the grenade and all I saw was a big crater. I knew then that I had got to the point of the thin line between sanity and insanity. I could tell that I was going mad. What saved me was that I told myself that I was not. If I could ask myself that question, then it meant that I was still all right.

I had many near-death experiences. There was once in Algeria when bandits surrounded my car at night whilst I was sleeping and ordered me out of the car. They spoke in Arabic but fortunately, the one who looked like their leader spoke a bit of French. They asked who I was, why I was doing this kind of journey all alone, and who was I spying for? I could tell from their arguments that one wanted me killed immediately because they were not sure what my mission was. One or two of them believed my story that I was just an adventurer. I kind of directed my answers and pleas to that one who spoke French in my own passable French to let them know that I was not any of what they suspected. They searched and found that I was not carrying the kind of money that would have (supported espionage). They rough-handled me and threw my stuff apart. A few of them just wanted to take everything in the car and get rid of me. Fortunately, their leader was a bit calm and he kept asking me questions whilst the rest were rampaging in anger. Meanwhile, the leader held on to my passport, a Nigerian passport. In the end, he gave me back the passport and shouted at the rest to stop scattering my things.

It took me eight days to cross the Sahara into Mali. From Mali, I moved to the Niger Republic and straight to the Nigerian embassy where I was received heartily, royally, and like a hero, by the Nigerian ambassador and his staff. After discussing with the ambassador and a few others, I found out that continuing from Niamey through Agades to Kano, was still going to be a journey through the desert, so I had to change course to go to Burkina Faso to enter Tamale in Northern Ghana and from there to Kumasi and Accra.

In Accra, I had a wonderful reception. I had pulled into a petrol station and the attendant, after looking at my car, asked me where I was coming from. I was not in the mood for any question and answer because I was tired. So, I said Tamale. The attendant asked, ‘Tamale?’ He added: ‘Oga, this car is not from Tamale.’ Anyway, because he was so excited and nice, I told him that I drove from London. He stopped dispensing the fuel. He looked inside the car again, and said, ‘Oga, wait.’ He went inside and the station owner was there. He came to confirm if it was true what his attendant had told him. I told him it was, and I showed him my passport. He looked through all the stamps, took me to his office, and said he would like to call the press. Within an hour, there was a media party. The following day, all the papers had my story. Then one Nigerian professor of literature in Legon, Ikedia, also decided to accommodate me, instead of staying in a hotel.

I did not plan to spend four, or five days in Accra but because of what happened, I spent four days there. I was invited to the university in Legon to give a talk on my mission. I was so very much at home. It was like a prince come to town. It was nice and warm. Everywhere. I stopped over in Togo, Lome, for a night. The extreme opposite of my experience in Accra happened when I got home, to Nigeria’s Idiroko border.

I had in my car all the Ghanaian newspapers which featured the story of my adventure. I showed it to the Nigerian Customs officers. They were reading the papers one after the other. That relaxed them a bit. In the end, they said that I had to pay the duty on the car but I did not have anything near the amount they called. I said maybe an officer could come along with me to Lagos and I could borrow money. They said that was not their practice. Anyway, they agreed that I could leave the car with them, go into Lagos, source the money, and come back and retrieve it. Maybe it was ignorance on my part because I had Carnet en-dual, an expensive international document that was prepared in London, which allowed me to take the car in and out of countries. So, I did not think well. But, they said, yes, they know about the documentation, but this was my country, and I was bringing in the car and I was not taking it out. I do not know why those who prepared the document did not think of it when I got to my destination.

So, I left the car, and took public transport, what they call bolekaja, into Lagos, after spending almost the whole day, thinking that someone would show mercy. They did not ask me for a bribe; they were just excited and most of them could not believe that it was true. When I got in, someone took me to Segun Olusola who was then Controller of Programmes on Nigerian Television and he arranged for me to be interviewed and then he introduced me to “Sad Sam” (Sam Amuka) who wrote a beautiful piece in the Sunday Times (I think). The news went around a bit, and Segun also introduced me to Ike Nwachukwu, then preparing to go to war. Ike Nwachukwu introduced me to Alex Akinyele who was then the public relations man of the Nigeria Customs Service. A signal was sent to Idiroko with a reduction of the duty. I went back and paid the duty and collected my car – and drove in, well, triumphantly.

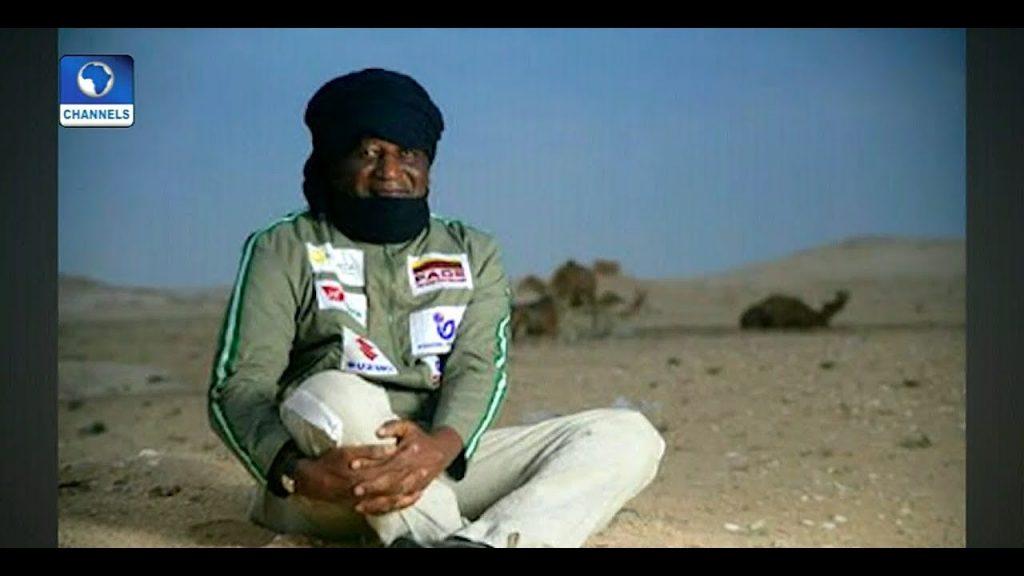

In all, this expedition took about two months. I would tell twenty-seven-old Newton Jibunoh today: Hold on to your dream if you dream at all. It was my dream that propelled and saw me through. It was my dream that also brought me to where I have been able to turn my explorations into a good cause and international advocacy and the activism against desertification that I find myself in today. That dream will remain in me till I die. J P Clark used to say that at this age, one is waiting at the departure lounge with one’s boarding pass. Fortunately, one is in good health….

More details of this solo trip, the one which followed, and the last group one in Jibunoh’s book, ME, MY DESERT AND I – A Journey. A Mission. A Life (New Edition) published in 2014 by TP House, Dallas, Texas, USA.

Pic: Austin Afam Ogah, in Asaba.

Culled from www.mytori.ng