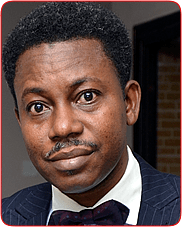

José Mourinho subsided in the same manner as so many of his teams this season: meekly and by degrees, with an impending inevitability and perhaps even a certain mercifulness. Indeed, if you want a measure of how far his stock has fallen, then consider the fact that his sacking by Tottenham Hotspur was not even the biggest football story of the day: one of the game’s great coaches reduced to a parish notice, a footnote in the foothills of football’s bold new future.

And so Mourinho will not lead Tottenham into the European Super League in which they have so controversially enlisted. Nor will he be given the chance to lift the 21st major trophy of his career in the Carabao Cup final against Manchester City. Instead, Ryan Mason will lead the team out at Wembley on Sunday: same players, different coach.

The first thing to say is that all this has been coming. Like one of the many leads Mourinho’s Tottenham managed to surrender over the last few months, a promising start has given way to caution, paralysis and misery.

There were statement wins against Arsenal (twice) and Manchester City (twice), a 6-1 victory at Old Trafford, a brief spell at the top of the table in November and December last year. Fleetingly it felt as if, amid the straitened circumstances of the pandemic, Mourinho’s grizzled brand of counter-football had met its ideal backdrop.

But the defining motif of Mourinho’s time at Tottenham will be those horrid last few months: a nauseating dirty pint of sour faces and sour football, of a team that had ceased to believe in itself and a coach who believed only in himself. In truth, Mourinho’s deep, low-possession style carried a certain logic in big games against superior opposition, particularly during last season’s torrid injury crisis. Harry Kane and Son Heung-min rediscovered their best form on his watch. Tanguy Ndombele has been transformed from junk asset to midfield jewel.

But the way they invited pressure against mid-ranking teams such as Crystal Palace and Wolves was not simply a betrayal of Tottenham’s recent traditions. In a squad stuffed with exuberant attacking talents it was a self-defeating, almost idiotic, approach. Time and turmoil seem to have congealed Mourinho’s preference for reactive football into a hard-wired ideology, the thrilling, shapeshifting coach of the mid-2000s devolved into a grimacing José Mourinho tribute act. As he approaches his seventh decade, Mourinho has become the thing he once despised most of all: a dogmatist.

So where did it all go wrong? Ultimately the blame lies with the chairman, Daniel Levy, in appointing a manager on reputation and celebrity wattage alone. Mourinho’s decline as a coach had been apparent for some years: the atrophying personal brand, the ossifying mindset, the increasing reliance on past accomplishments. And yet for a club nursing deep status anxiety, he seemed to fulfil some deep-seated need in Levy to be seen as a proper grown-up in charge of a proper grown-up club. A gleaming new stadium, a soft-focus Amazon documentary and now one of the most marketable managers in the game. And the football? Well, that could take care of itself. Just look at the guy’s CV. The man’s a trophy machine.

Alas, Tottenham were the first club to discover that in the modern game Mourinho’s thirst for silverware is outstripped only by his thirst for excuses. A squad that Mourinho declared was “better than I had at Manchester United” had, by the end of his first season, been recast as an emaciated skeleton in desperate need of investment. In came Gedson Fernandes, Matt Doherty and Carlos Vinícius. Pierre-Emile Højbjerg, Steven Bergwijn and Joe Rodon have shown promise. Gareth Bale, one of the feelgood signings of the summer, has been unapologetically and expensively frozen out.

On and off the pitch, meanwhile, the tight-knit unity fostered under Mauricio Pochettino was blown apart in a matter of months. There have been needless feuds with Ndombele and Dele Alli, punishment substitutions, a vindictive focus on individual mistakes, a cowardly insistence on using his players as a riot shield. And to what end? As ever, Mourinho leaves a bloated and uneven squad riven by grudges and rifts, a mixture of players who can’t wait to leave and players barely good enough to stay. This is, as Mourinho himself once observed, football heritage.

What now for Tottenham? A new manager and a new dawn: perhaps even the sort of late-season bounce that could catapult them back into the top four (they are seventh) and win them a first trophy since 2008. But something fundamental also seems to have been changed over the last 17 months. This goes beyond the pandemic or a single choice of manager. Levy’s recent decisions have reinforced the notion amongst Tottenham fans that theirs is a club that is being run in their presence, but not really for their benefit: a rift between front room and boardroom that will not be healed in a hurry.

What of Mourinho? A handsome payoff and an extended period of gardening leave: off he goes, back to the great television studio and Paddy Power advert in the sky. And in a way, there is a certain symbolism to how the last couple of days have panned out. With one breath, Tottenham have sketched out a staggering new future. With the next, it has consigned its famous old coach to the past. Two decades into his career, modern football may very literally have left Mourinho behind.