By Liam Kirkaldy

In 2010, the BBC aired a documentary called Welcome to Lagos that explored life in one of the fastest growing cities in the world. It was a three-part mini-series, surveying the changing hopes and aspirations of the city’s poorest residents, and taking viewers from houses constructed with scrap on the beach, to the people living in Olusosun rubbish dump. Shown on BBC2, the production company behind it went on to win a Bafta.

But, most importantly, episode two of the series included a look at Makoko – a community built on stilts, on top of Lagos Lagoon – where a resident called Chubbey explained that survival in the city required a certain degree of street smarts.

“Anybody who came to Lagos and he didn’t learn sense, he cannot get sense ever,” he said. “Because here if you are a fool, they will learn you how to get sense. If you are a ‘Dundee United’, when they start to pour shit on you, you will get sense.”

After that the scene cut away and the documentary continued. But for any Scottish football fan watching, the producers had missed an important story: Dundee United is used to mean “idiot” in Nigeria.

It is an upsetting thing to think about, for a United fan. This is a country of over 200 million people and they have apparently been using Dundee United as a byword for a fool for years. Why would they do this?

It doesn’t make a lot of sense, but it’s true. As Yewande, a Nigerian-Scot based in Glasgow, explains: “When I was little, living in Nigeria, it was quite common. People would say ‘you’re just a Dundee United’, or ‘don’t be a Dundee United’, and it basically means an idiot or a loser.”

But why? And how did it happen? Dundee United, unfortunately, did not respond to requests for comment on the question. The club’s silence represented an early blow to an investigation that already appeared as complicated as it was pointless. Yet a glance at the internet shows theories do exist. One, popular on online chatrooms, is that the phrase stems from the 1989 FIFA under-16 world championships.

The tournament was actually a very successful one for the Scotland under-16s team, which made it to the final before losing to Saudi Arabia on penalties. Records show Nigeria were also present, with the team knocked out by the Saudis in the quarters.

Significantly, that match was played at Dens Park. In fact the ground was home to four of Nigeria’s games, and the team also trained there. So could this be the answer? Is it possible that a contingent of mischievous Dundee fans could have played a part in the origins of the phrase? Could they have taken it upon themselves to inform a group of 15-year-old Nigerian youth players that “Dundee United” was local slang for an idiot?

Experience of Dundee fans would certainly suggest it is plausible. Yet use of the phrase seems to go back further than the late 1980s, with a TV ad for an anti-malarial drug, shown in Nigeria years before, including use of the term. That means that by the time the 1989 world championship was taking place, the Nigerian youth team players would have been well aware that a Dundee United was a foolish thing to be.

In fact, while the full phrase is “Dundee United”, it seems time and repeated use has seen it worn down to just “Dundee” on occasion. In other contexts, a “Dundee” can be used to refer to one idiot, while ‘Dundee United’ has become the plural, for a collection of idiots. That means that, even if the Dens Park theory is right, it would seem to have backfired.

Fatima, a Nigerian-Scot based in Aberdeen, explains: “A ‘Dundee’ is quite a common phrase in the north [of Nigeria]. I heard it a few times from relatives. If a wee kid was misbehaving or something, or someone does something really stupid, you’d say “Dundee”, sometimes followed by the word “mumu” which really just means the same thing. But because of the way it is pronounced I hadn’t thought of Dundee, the city in Scotland. I knew the phrase but never made that connection at all.”

Derin, a Nigerian-Scot from Glasgow, adds: “There are different options for how you might use it. When I was a child you would hear it a lot more, because it’s a bit less offensive than saying ‘stupid’ or ‘idiot’, or something in one of the languages, because they always sound slightly harsher, so that was used instead. You’d hear it sometimes as Dundee United, or sometimes just Dundee. If someone called you a Dundee you could go ‘Dundee United’ back at them, to prove you know the full thing, as a way of getting one-up on them.”

It was an unfortunate blow for the team languishing in the Championship, but an important development in the investigation: whatever the reason, Dundee also means an idiot in Nigeria. Unfortunately, Dundee FC were apparently unaware of this. In fact, although initially happy to confirm that the phrase “Dundee United” means an idiot in Nigeria, after being informed their own team had also been dragged into the whole sorry affair, the club were unable to help further. Dundee United still did not respond to requests for comment.

But if the phrase doesn’t come from the late 1980s, where does it come from? A second theory, popular among some Nigerians, is that it stems from a few years earlier, when United reached the semi-finals of the 1983-84 European Cup. Their tie, against Roma, is seared into the memories of United fans.

Jim McLean’s team won the first leg 2-0, only to lose 3-0 away, with subsequent reports suggesting Roma had attempted to bribe the referee the night before the game. And so, according to this version of events, use of ‘Dundee United’ stuck after large numbers of Nigerians backed United at the bookies, only to lose big as Roma headed off to meet Liverpool in the final.

Olumide, who lives in Glasgow, says: “The players were basically just looking, as the other team took the ball off them. They behaved exactly like fools and it didn’t go down well with the gamblers. The Nigerian gamblers then lost their money, and so, out of frustration, anyone who under-performs, or behaves sluggish, or isn’t up to a task at the level expected was, and is still, referred to as ‘Dundee United’ by Nigerians.”

And on the face of it, like the Dens Park theory, this seems reasonable. The game was a high profile one, held in an explosive atmosphere, and clearly the turnaround would have come as a shock. But could it really have seen thousands of Nigerians place bets on United, then lose their hard earned savings? And would that have been enough for the team’s name to become shorthand for idiocy, across an entire nation, for the next 40 years? The game did little to improve impressions of the club among Nigerians, and it may well have helped cement the phrase. But again, the story seems to go even further back.

The answer lies in a two-week period, between the end of May and the start of June, 1972, and a disastrous club tour of West Africa. The trip really did go very badly indeed. United were matched against small, local teams, and they were woeful. Records from the tour reveal a middling start, with a 2-2 draw with Stationery Stores on 27 May 1972 followed by a 1-0 win against Benin Vipers on the 31st. That, however, was to mark the high point of the visit – United lost 2-0 to Enugu Rangers on 3 June, in a match played in front of 35,000 people, before drawing 1-1 with Mighty Jets on 7 June, and then ending the whole sorry affair with a 4-1 hammering at the hands of Stationery Stores.

These were amateur teams, and local fans had expected much, much more from a representative of Scotland’s top flight. United looked like fools. There are, of course, mitigating circumstances. The tour was a hectic one, coming at the end of a long season, with United’s players apparently thrown by travel arrangements and ill-equipped to playing five games over 16 days, in Nigeria in June.

Looking back at the context surrounding the trip, it is questionable how much anyone from the United camp really wanted to be there in the first place. Jim McLean had only been manager for five months and, despite rumours he actually played in some of the friendlies – he was 34 at the time and had only recently retired – it seems likely he was pretty unhappy about the idea of taking the team over to western Africa.

The plans had been drawn up while Jerry Kerr was still coach, and by the time McLean took over it was too late to pull out. So while it’s probably fair to say McLean was at least quietly unhappy about the prospect of flying his team halfway across the world at the end of a hard season, he had yet to achieve the sort of control he would later exert over the club and was left with no choice but to get on the plane.

An article published in the Nigerian Daily Express as United returned to Scotland probably sums up the general feeling towards the club. It is headlined: “Don’t Come Back”.

“Football followers in this country were very happy in the sense it would give them another opportunity to witness a first class Scottish team,” it says. “But alas, what we saw was in fact a direct opposite of what we expected. The argument adduced by some people was that the visitors had been overworked or tired out, but this does not seem to hold water and they are not the first English [sic] team to tour Nigeria under the same weather conditions. We must agree that they are just not good. They had nothing to offer Nigeria as far as football technique and artistry are concerned, it is as simple as that.”

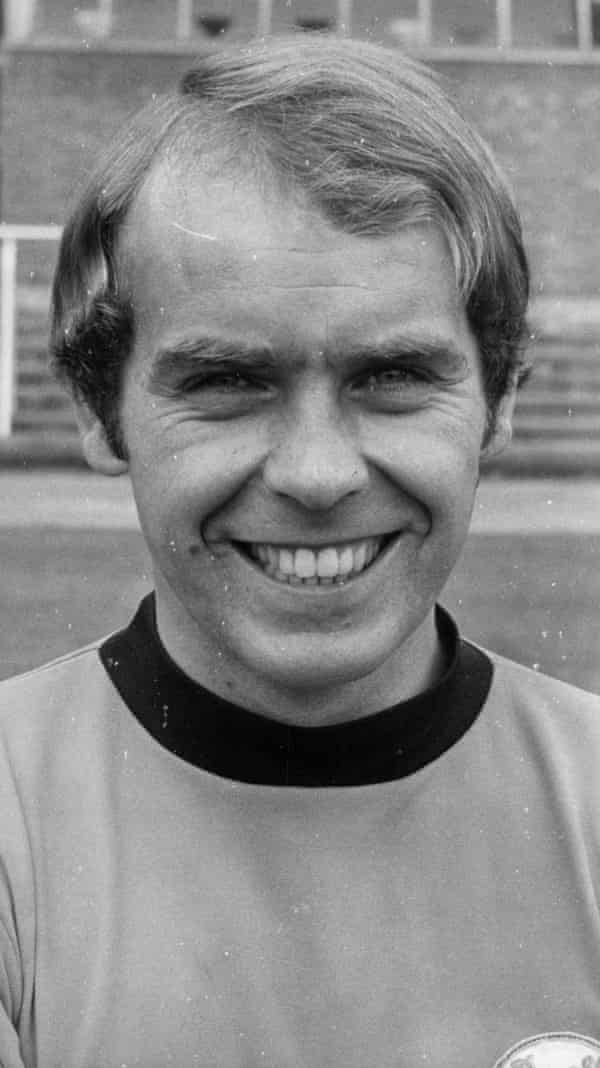

Meanwhile, poor performances were combined with increasing tension in the Nigerian press over United’s attitude. Things reached a head with a Sunday Post article – reproduced in full in Nigerian newspapers – in which United forward Kenny Cameron complained of stomach bugs in the squad, as well as post office strikes and traffic jams. “Their traffic problem is far worse than that of the High Street in Dundee,” he complained.

Relations deteriorated even further when Cameron claimed the team had been met at the airport by “vultures and hyenas”, before suggesting that their struggles were down to the humidity, as well as logistical disruption caused by the Nigerian Football Association. That was a step too far for Nigerian fans and media. Lethargic performances were one thing, but the United centre-forward claiming large carnivores were wandering around the airport was quite another. The response was furious.

A complaint to the New Nigeria newspaper – questioning not just Cameron’s claim but the editorial judgement behind reporting it – summed up the mood across the rest of the media: “As a Nigerian, and a very patriotic one for that matter, I cannot forgive Mr Cameron for saying vultures and hyenas made up their reception committee at the Kano airport. But then Mr Cameron was only being true to type. It is a fact that European reporters who visit Africa only file back what their kinsfolk want to read: bizarre and irrelevant happenings.”

The Renaissance, a daily newspaper from Enugu, in the south-east of the country, went one step further. It was so incensed by Dundee United’s failings that it called for a public inquiry. It reported: “Dundee United came – a first division Scottish team! They played football – second rate. And Nigerians were treated to second rate amateurism. This is the level to which we are plunging this country. Can someone save us these pains? We need an inquiry, why did the Dundee come? For now, Dundee fare-well. For Ever, Good-bye.”

The demand for a public inquiry may seem a strong reaction to a win, two draws and two defeats – and it is worth keeping in mind that these were exhibition matches – but aside from showing where the Dundee-Dundee United confusion came from, the piece is pretty representative of the rest of the press. From there, it seems, a seed had been planted. Aided by media coverage, the name stuck, and from early June 1972 onwards, a Dundee United was a fool in Nigeria.

Yet, as time passes, and with United no longer hitting the heights of their success in the 1980s, it seems the phrase has become so disconnected from its origins that many Nigerians will call each other Dundee Uniteds, or Dundees, without knowing either football club exists.

Many of those approached for comment were somewhat surprised that someone in Scotland would name a football club as the byword for an idiot, while other interviewees offered a quiet embarrassment on Dundee United’s behalf. The existence of Dundee University too must be somewhat confusing for those who only know the word from the Nigerian use.

Amara is a Nigerian-Scot who works in Dundee, but says that he has never felt the need to mention use of the phrase to colleagues. “Some of my colleagues ask me about Nigeria, and one is actually a Dundee United fan, but I’ve never told them,” he laughs. “I didn’t think there was any need.”

“I was actually in Nigeria just before the Covid outbreak and someone in the pub was calling someone a “Dundee United”, because they were yapping [teasing] their friend, and I said: ‘Do you know there is a football club in Scotland called Dundee United, and they said ‘No? Really?’ They thought it was a really strange thing to call a football team. I explained about the city and that it was a football team and they thought it was pretty funny…”

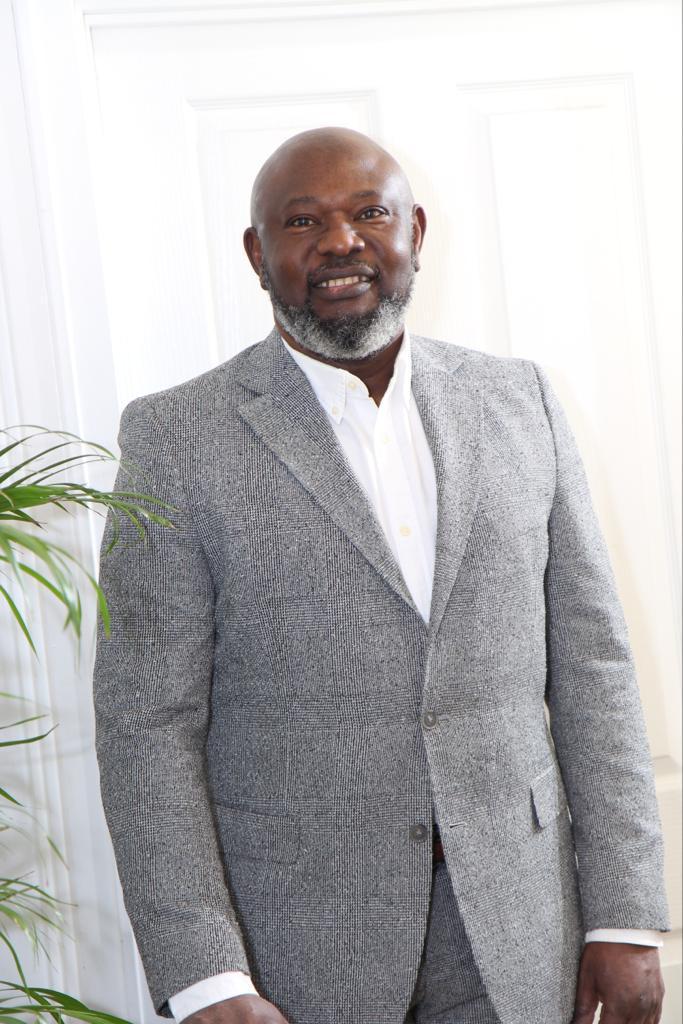

And so it seems use of the phrase continues. But what about Chubbey, the man who introduced Scotland to the label back in 2010? As it happens, he left Lagos years ago. His full name is Morrence “Chubbey” Ojulowo, and he now lives in Ondo state, where he enjoys a quieter life, in a village a few hours’ drive from the capital.

He says he is happy and in good health, though he was slightly bemused to learn of his role in the story. He is 75 years old now, with 17 grandchildren, and while he goes back to visit Lagos pretty regularly, he was apparently completely unaware of his role in introducing the Nigerian use of “Dundee United” to Scottish football fans. Approached for comment, he just laughed.

The Guardian