Reflecting on how African music crossed over into wider pop culture.

This piece was created in partnership with Afro Nation. Billboard and Afro Nation recently launched the first-ever official Billboard Afrobeats U.S. Songs Chart, tracking the most popular rising new music in the rapidly growing genre. The 50-position Billboard U.S. Afrobeats Songs chart, which will go live on Billboard.com on March 29, ranks the most popular Afrobeat songs in the country based on a weighted formula incorporating official-only streams on both subscription and ad-supported tiers of leading audio and video music services, plus download sales from top music retailers.

The late great Randy Weston was an African-American pianist emerging from the jazz scene, or as he triumphantly called it, “African Rhythms.” He first arrived on the African continent for the first time in Lagos in January 1961, and after visiting West Africa for a number of years, he would later remark, “After hearing the various types of music (in Africa) we in the United States were just simply an extension of Africa, being like almost the beginning of life itself and like it’s thrown itself out in different parts of the world.”

This Pan-Africanist attitude relates to the Akan tradition of Sankofa, which translates, “to go back and get it.” During the late 1950s to 1960s, when former African colonies became independent nations in their own right, this guiding spirit travels across the “Black Atlantic” – a term originating from British academic Paul Gilroy, reflecting upon the violent migration of Africans via the triangular slave trade between Africa, Europe and North America. A Black consciousness has developed creatively back and forth across these important locations, with Black vernacular and popular culture personified as “the polyphonic qualities of black cultural expression.”

In this piece, we’ll reflect on how the Pan-African attitude has shifted from truthful social commentaries through big bands from the motherland to influential milestones in cities such as London, where individual pop stars now flourish on the global stage. London has been a key location in connecting with the wider African diaspora and providing a finishing school for popular artists such as Wizkid, Burna Boy, and Davido to regularly sell out the O2 Arena. It’s this reconnection with your roots in real-time, whether physical or via the internet, which produces Drake’s worldwide crossover hit “One Dance,” featuring Wizkid and Kyla; similar energy saw Beyoncé lean on many leading protagonists in the Afrobeats scene for her Grammy-awarding soundtrack album, The Lion King: The Gift, giving the sound an unprecedented level of exposure around the world.

In this present age, Afrobeats is an electronic extension following this same route, taking in Nigerian Afrobeat and Ghanaian highlife with reggae and dancehall sensibilities, which has crossed over to the mainstream and is slowly infiltrating the U.S. airwaves. Its global popularity is marked by Grammy wins viral dance challenges and sold-out arena tours.

The geographical routes of pain are now transformed into a positive and defining soundtrack for migrant communities in the African diaspora to have a clearer connection to their roots via music as a safe space. However, as important as it is to look ahead, it’s just as important to reflect back on the rise of African music and its crossover into wider pop culture through a number of landmark moments across the Black Atlantic.

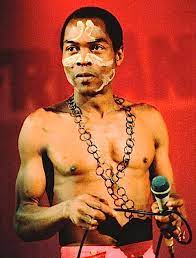

Born Fela Anikulapo Kuti on October 15, 1938, the pioneer of Afrobeat with a middle name meaning, “One who carries death in his pouch,” carries a fearlessness that follows his discography through honest social commentary on the dying embers of colonialism and its effect on the biggest population in Africa. Afrobeat is a genre with the familiar universal appeal of jazz, soul, and Ghanaian highlife, alongside the polyrhythmic drumming foundations of the Yoruba, Ewe, and Ga tribes.

This balance of West African traditions and movements across the West parallels the late Nigerian musician’s own personal story – leaving his motherland for England in 1958, enrolling at the Trinity College of Music in London, and forming his Koola Lobitos group with a West African and Caribbean lineup, blending jazz and highlife a few years later. The Koola Lobitos would enjoy initial success upon his return back to Nigeria, but their popularity would soon fade with his influential mother Funmilayo asking him to “start playing music your people understand, not jazz.” During this soul-searching period, Kuti traveled to Ghana in 1967 and started to build inspiration for a new musical direction he would christen Afrobeat.

A 10-month tour in the U.S. in 1969 with Nigeria 70, coincided with the height of the Nigerian civil war, which would also prove to be a turning point for Kuti, further revolutionizing his approach to music and simultaneously heightening his political consciousness. He stated, “When I got to America, I was exposed to African history which I was not exposed to here…I had been using jazz to play African music when really I should be using African music to play jazz. So it was America that brought me back to myself.”

Upon his return, the band changed their name to Africa 70 as well as his local Afro-Spot club to the seminal Afrika Shrine. The venue became a key spot for Kuti to fine-tune his showmanship through call-and-response musical arrangements to keep the African element at its core, alongside the increasing influence of inspired soul on a nightly basis.

Simultaneously, this period of the late 60s to early 70s included a number of visits from African-American artists, such as James Brown, who toured Nigeria in 1968, and the legendary Soul-to-Soul concert held in Accra in 1971 — which saw musical powerhouses in Wilson Pickett, Ike, and Tina Turner, and Roberta Flack — all in attendance. It would further inspire a young generation of dance-band highlife bands and fans across West Africa.

In Ghana, the late 70s would see the decline of the live popular music scene due to mismanagement and the military regime governments, where the Ghanaian economy collapsed. A combination of a nighttime curfew between 1982 and 1984, and a heavy import tax duty on band equipment, persuaded a number of Ghanaian musicians to leave the country to relocate abroad. Hamburg was a location in which a large influx of Ghanaian economic migrants settled, with the port city becoming well-known for a new fusion genre called Burger Highlife in the early 80s, highly computerised in nature compared to live horns and drums of highlife. This North German city is a key location where the close proximity to state-of-the-art music technology in synthesizers and drum machines often had sonic siblings in disco and funk.

Popular early Burger Highlife musicians like Lee Dodou, George Darko (who released the popular record “Akoo Te Brofo” in 1983) and Pat Thomas brought distinct approaches, having honed their craft in big dance highlife bands. Whilst the most popular artist to emerge from the genre was Charles Kwadwo Fosu, aka Daddy Lumba, this shift from the collective to the individual superstar also reflected a growing shift in messages behind the music, where a range of societal topics via moral advice and family problems were replaced by fewer individualized commentaries on love and marriage.

The 1990s would see another influential genre in the rise of Afrobeats emerge back in Accra, Ghana. Inspired by classic highlife samples, but more readily influenced by African-American global superstars in rap and hip-hop, Hiplife’s emergence in the mid-1990s owing to the exodus of highlife past masters and a new generation of Ghanaian youth redefining their location on the musical map with a fresh democratic government installed. Rappers such as the godfather of Hiplife Reggie Rockstone, Tic-Tac, Obrafour and Akyeame — all rapping in local languages of Twi, Ga and Ewe – boasted familiar cadences to DMX and Busta Rhymes, over West and East Coast-inspired instrumentals.

A connection between Africa and the wider diaspora was reinforced from the late 90s to the early 2000s within the UK, through regular attendance at independence day events celebrating their respective motherlands. In London and the South East, at venues like Stratford Rex and The Dominion Theatre, a subconscious change was taking place at hall parties through Hiplife alongside Afro-Pop and Naija R&B, with a young generation of British birth and West African heritage referencing songs to stay connected to their mother tongues and build pride through this annual sense of community.

The Black African population within England and Wales was higher than their Caribbean counterparts for the first time, with this same demographic also having greater levels of entry into higher education. This growing population and their route into higher education would soon plant the seeds for an influential rave scene emerging from the Afro-Caribbean Societies at key universities around the M25 of London and the further north in the East Midlands of the UK.

The soundtrack to these ACS club nights encompassed the polyrhythmic productions of UK funky and the grime energy of MC-led tracks, where Patois and Pidgin English fused with syncopated London slang. This heralded a plethora of dance crazes, commonly known as skanks, that opened the door to the dance-led Azonto movement, Afrobeats and the Afro-affiliated subgenres which have crossed over globally in the last few years.

The DIY nature of this uni rave scene was a foundational base for artists such as Afro B and Mista Silva to emerge during the first wave of UK Afrobeats, via curated mix CDs from influential DJs like Larizzle and P Montana, who blended songs like Magic System’s classic “Premier Gaou” and early Wizkid’s “Pakurumo.” DJ Abrantee’s “New Afrobeats Show” on Black British radio station Choice FM, along with the popularity of Fuse ODG’s Azonto and D’banj’s “Oliver Twist” — the first Afrobeats song to reach the UK Top Ten — gave a new generation real models who controlled the narrative and embraced their African heritage with pride.

Its unapologetic energy that attracts more African-American collaboration in the spirit of Sankofa. African artists set the pace for global pop via streaming platforms and curated festivals, which show the depth and distinction of music emerging from the continent with the world’s youngest population and its ride-or-die diaspora community in tow.

Christian Adofo is an established writer, cultural curator, and author from North London. His debut book, A Quick Ting On Afrobeats, published by Jacaranda Books, is out now.

Stay ahead with the latest updates!

Join The Podium Media on WhatsApp for real-time news alerts, breaking stories, and exclusive content delivered straight to your phone. Don’t miss a headline — subscribe now!

Chat with Us on WhatsApp