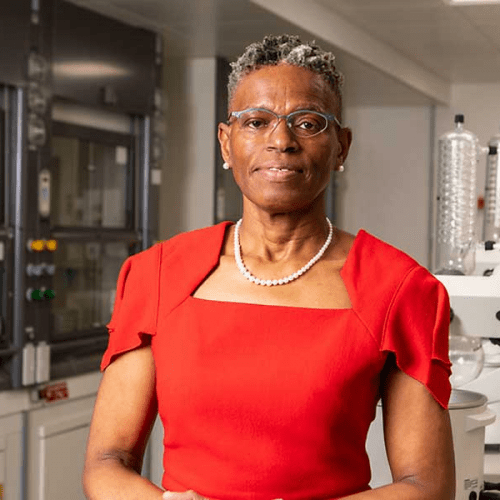

In 1982 the French international Jean-Pierre Adams went to hospital and was given anaesthetic that should have knocked him out for a few hours. 32 years later, he has yet to awake

The following is an extract from Robin Bairner’s article from the forthcoming Issue Twelve of the Blizzard. The Blizzard is a quarterly football journal available from www.theblizzard.co.uk on a pay-what-you-like basis in print and digital formats.

On 17 March 1982, the former France international footballer Jean-Pierre Adams, at the age of 34, was admitted to a Lyon hospital to undergo a routine knee operation. He was given anaesthetic that should have knocked him out for a few hours but, more than 30 years later, he has yet to awake.

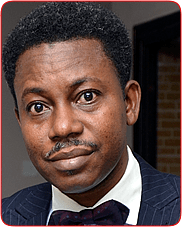

Adams is a figure who drifts in and out of the consciousness of the French public but who is largely forgotten outside his homeland, despite being a highly-regarded figure as a pioneer for French-African footballers. With 22 caps to his credit, he turned out more regularly for Les Bleus than David Ginola, Ludovic Giuly and even Just Fontaine, carrying himself with a humble spirit and a ceaseless smile.

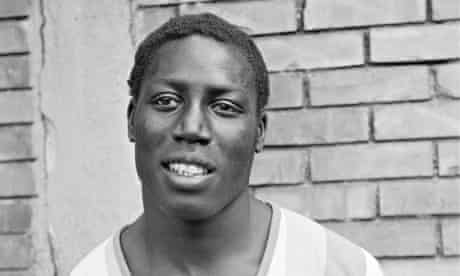

His story begins in Dakar, Senegal, where he was born on 10 March 1948, the oldest child of a large family. Although football was in young Jean-Pierre’s blood – his uncle Alexandre Diadhiou played for the celebrated Jeanne d’Arc club – education was made the priority in his life by his devoutly Catholic family and he was not allowed to play the sport he loved unless his grades in school were of a sufficient standard.

With this in mind, Adams was sent alone to continue his schooling in France, where he was ultimately fostered by the Jourdain family in Loiret, a department a little south of Paris.

Football proved to be a vital release for the adolescent Adams. It also provided him with an environment in which to socialise in what was still a white-dominated society as he swiftly gained respect for his physical prowess and his endearing personality. He would very quickly become popular at Collège Saint-Louis, where he was affectionately known as the “White Wolf”.

Away from the pitch, Adams completed his initial schooling but elected to drop out of a course studying shorthand as it did not interest him. Instead, he worked in a factory as his game progressed to Montagris.

However, there was a hint of problems to come as he suffered a serious knee injury that could have ended his dreams of becoming a professional footballer.

Even after moving to l’Entente Bagneaux-Fontainebleau-Nemours (EBFN) misfortune continued to follow him. Adams was involved in a serious car crash, and though he escaped with only cuts, his close friend Guy Beaudot was killed.

To have been touched by such troubles at the age of 19, it was little surprise that Adams’ appetite for the game was briefly diminished. Military service, however, proved to be a turning point. Adams had always been a physically imposing specimen but his time in the army meant his talents started to become recognised in a broader sphere. He was selected to play for the military squad, from which he would be recommended to Nîmes.

Adams’s desire to become a professional had been further fired by his marriage to Bernadette. Even this had been no straightforward pathway, though, as his blonde bride’s mother had initially refused to give her daughter’s hand to the young African.

At this point, Adams took a path similar to that of Lilian Thuram, who rose through the amateur ranks to become one of the game’s most celebrated players. Thuram also turned out for the latter-day version of EBFN, yet it was during the era of Adams that the club became prominent in the nation’s amateur game.

In three successive years, with Adams their driving force, they would lose the Championnat de France Amateurs final, before earning the right to play in an expanded Division 2 in 1970. Although EBFN were coming up short as a team on the big occasion, Adams’s career was taking off. The strides he made during his military service persuaded the Nîmes trainer Kader Firoud to offer Adams a trial match in Rouen. Bernadette drove Jean-Pierre north for the friendly in which her 22-year-old husband impressed sufficiently to earn his first professional contract.

Firoud would be one of the key influences on Adams’ career. He was a terrific motivator, although his training methods were unorthodox. However unconventional the coach, his methods were highly effective. Only the Auxerre legend Guy Roux has overseen more top division matches than Firoud’s 782, and in 1971 he was named France Football’s Coach of the Year. Crucially for Adams, he was particularly effective at bringing through unknown quantities from the youth ranks.

After making his debut in a new No4 role against Reims in September 1970, Adams would become a permanent fixture in the team.

It was no mean achievement to become established so readily. Nîmes’s side at the time was one of the best in the club’s history and Adams was a fulcrum as Les Crocodiles qualified for Europe for the first time. He was decisive in the club’s first Uefa Cup win, though Nîmes lost the tie on away goals to Vitória Setúbal of Portugal.

Such a narrow defeat was the prelude to a frustrating second season in which the club finished as runners-up to Olympique Marseille. Nîmes paid for a poor spring run that saw them win one of seven league matches and rendered futile their eight wins from nine at the campaign’s conclusion.

On a collective level, Adams’s third and final season at the club was disappointing as Les Crocos finished only seventh, yet the midfielder remained “in international form”. “In the rugged defence of Nîmes, there is a pillar, a kind of force of nature, a colossus of uncommon athletic power: Jean-Pierre Adams,” said the former Argentina captain Ángel Marcos, who played for Nantes. “I always dreaded the two annual confrontations [with Adams].”

When Adams moved to Nice in the summer of 1973, Marcos didn’t have life any easier. By then a France international, Adams was at the peak of his powers. Nice at the time were ready to spend. An ambitious bid to sign Jairzinho failed narrowly as they attempted to re-establish themselves as a major force after dropping out of the elite in 1969.

Despite their spending, their return was marked with a disappointing 14th-place finish but, by the time Adams arrived, Nice were rueing a failure to win the title the previous season, having thrown away a five-point lead to allow Nantes to overhaul them.

Life for Adams on the Côte d’Azur started with some promise as two goals from Marc Molitor and another from Dick van Dijk helped Nice secure a 3-2 win over Barcelona in the Uefa Cup. By the time their European run was emphatically ended with a 4-1 aggregate defeat to Köln – a tie played without Adams, who had been suspended after a red card against Fenerbahce in the previous round – the head coach Jean Snella found his position becoming increasingly uneasy. League results were not good and after a fifth-place finish he was dismissed.

His replacement was Vlatko Markovic, an ill-fated appointment. Markovic was never popular among the Nice fans. “If spectators want a spectacle, they should go to Marineland,” he said following criticism of his dour playing style.

Despite the coaching sideshow, Adams remained a consistently strong performer and was named in France Football’s team of the season. “Adams remains without a rival in his role, where his extraordinary athletic qualities can match the best,” the magazine gushed.

In the subsequent campaign, Nice finished second behind Saint-Etienne, a series of injuries to their best players probably robbing them of the title. Adams was one of the men who suffered most and those issues would mark the end of his personal peak after dropping out of the national team.

Adams’ introduction to Les Bleus had come five years earlier during the Taça Independência, a competition played in Brazil to celebrate the 150th anniversary of the nation’s independence from Portugal. Fittingly, his debut came against an Africa select team, as he arrived off the bench to replace Marius Trésor, the man with whom he would form the fabled Garde Noire in years to come.

Five days later he was handed his first start against Colombia. It began inauspiciously as Adams conceded a penalty from which the South Americans took the lead but he showed his resilience thereafter.

The coach Georges Boulogne was sufficiently impressed to pair Adams with Trésor in defence for a decisive encounter with Argentina that would decide which country progressed to the second round. A scoreless draw meant disappointment for France, who were eliminated on goal difference. They were compensated with the birth of La Garde Noire.

Like all good double acts, Trésor and Adams complemented each other. The former was regarded as the technical defender while Adams was noted for his athleticism.

While Trésor was born in Guadeloupe, Adams’s sub-Saharan roots were something of a novelty in the France team of the time. Of course, France had seen other such “foreigners” turn out for its national team previously; the great ball juggler Larbi Ben Barek hailed from Morocco but won 17 caps, while Xercès Louis (12 caps in the mid-50s) and Daniel Charles-Alfred (four caps in the mid-60s) were both born in Martinique. And of course there were Just Fontaine, Rachid Mekhloufi and Mustapha Zitouni, who came from North Africa.

Adams was laying a pathway from west Africa to France for the likes of Marcel Desailly and Patrick Vieira to follow.

France may have been welcomed back from Brazil warmly but it was not until they met the USSR in a World Cup qualifying match that their new central defensive pairing really came of age. The Parisian venue had been something of a bête noire for Adams in the past. He had lost two previous CFA finals at the ground, leading the press to dub it his Stade du Désespoir – Stadium of Despair.

A free-kick from Georges Bereta proved decisive for France but it was the performance from the centre-backs that was truly match winning. Franz Beckenbauer held the duo in particularly high regard, remarking to Onze: “Adams and Trésor have formed one of the best centre-back pairings in all of Europe.”

Once again, however, injuries had a telling impact on Adams. His persistent troubles saw his partnership with Trésor broken up in 1975 and Adams never again turned out in France’s blue.

Adams soon moved back north to the familiar surrounds of the Paris region. The ambitious PSG president Daniel Hechter had been seduced by him amid the club’s first period of big spending. Hechter was a very astute businessman and played a key role in the early development of the club, lifting them from the amateur ranks to overtake Paris FC as the capital’s primary power.

As the 29-year-old’s experience at Nice had shown, big spending did not necessarily equate to big rewards and Adams’ time in Paris was subdued, with two mid-table finishes before he was released from his contract, ending his time at the top level.

A brief and unsuccessful stay at Mulhouse followed before Adams took the decision to step into coaching.

Adams had elected to take the first stage of his coaching degree in Dijon, which meant going on a week-long course in the Bourguignon town during the spring. On the third day, however, he suffered a knee problem and the following morning quit the course for a hospital in Lyon. An initial scan showed damage to a tendon at the back of the knee but a chance meeting with a surgeon en route to the exit proved critical. After a discussion, it was decided that the best course of action would be to operate. Adams agreed to an operation a matter of days later on 17 March.

“It’s all fine, I’m in great shape,” were his parting words to Bernadette as he left on the morning of the operation.

His wife was worried and only more so when it took three calls to the hospital before she was passed on to a doctor. “Come here now,” she was told gravely.

Adams had slipped into a coma. Bernadette remained by his bedside for five days and five nights hoping for a change in his condition while the couple’s two young boys, Laurent and Frédéric, were at home with their grandparents.

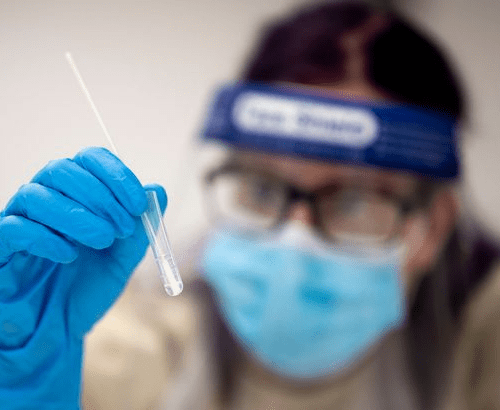

There had been a problem with Adams’ supply of anaesthetic, which was exacerbated by the fact the anaesthetist was overseeing eight operations at once, including one particularly delicate procedure involving a child that got much of his attention. To complicate matters further, Adams was not on the correct type of bed, the drug used was known to be problematic and the operation was overseen by a trainee.

Adams has never woken.

It would be November before he was moved north to Chalon, where Bernadette was by his side on a daily basis. That did not prevent Adams from being neglected by the staff at his new institution. After finding an infected bed sore, Bernadette exploded with rage and, after her husband had undergone another operation as the infection had reached his bones, she sat with him continuously, still holding out hope he one day might wake.

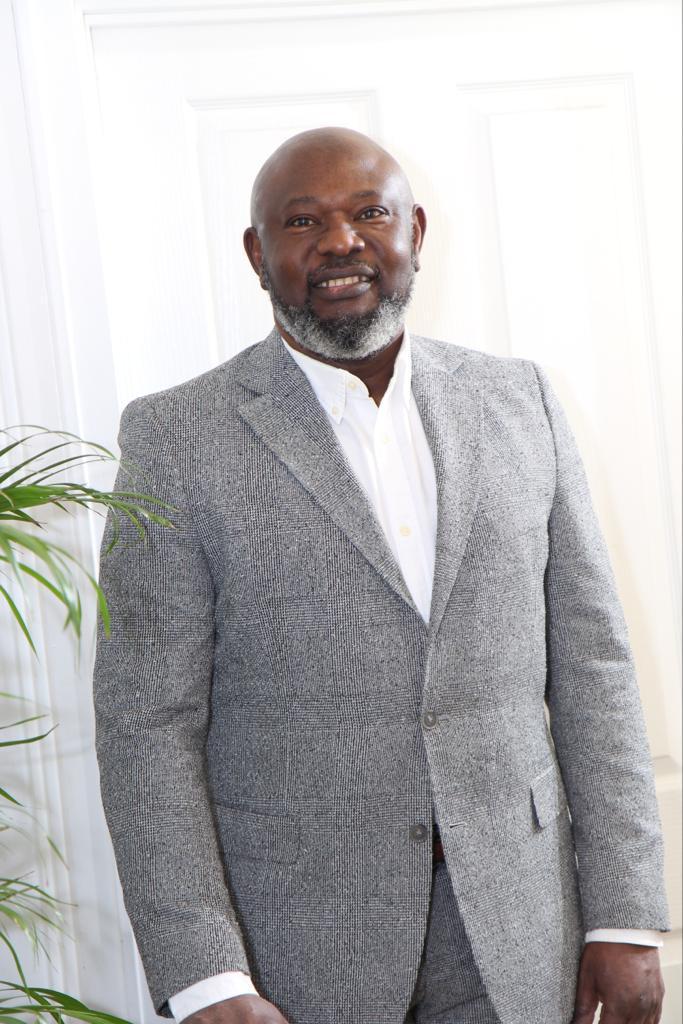

When the hospital said they could no longer look after Adams, he was moved home. For Bernadette this was a great undertaking. She would sleep in the same room as her husband and get up in the middle of the night to turn him.

Bernadette had a house custom-built, which she named Mas du bel athléte dormant — the House of the Beautiful Sleeping Athlete. It had been a struggle to get a loan in place, however, as she had fallen into difficult financial circumstances.

Various bodies came forward to help, with Nîmes and PSG both offering 15,000 francs, while the French football federation gave her F6,000 per week after an initial contribution of F25,000 in December 1982.

In addition, Adams’s former clubs played charity matches. The Variétés Club de France, a charitable organisation still running today and backed by Platini, Zinedine Zidane and Jean-Pierre Papin, played a fixture in the comatose player’s honour against a group of his footballing friends.

The media, meanwhile, kept his memory alive with glowing testimonies. “[Adams] was the prototype of a modern-day midfielder,” wrote the journalist Victor Sinet. “He was always available, omnipresent and just as effective going forward as he was defending.”

Meanwhile, the courts deliberated upon the case in a sluggish manner.

Pierre Huth, Adams’s former doctor at PSG, led the case, which went on for seven years before the Seventh Chamber of Correctional Tribunal in Lyon found the doctors guilty of involuntary injury. It was only at that point that the family’s dues could be calculated, yet four years later a definitive decision had still to be made.

Life, such as it is, continues for Bernadette and Jean-Pierre. Hospitals cannot commit staff to looking after Adams for long periods of time, which prevents his wife from taking holidays. Each day Jean-Pierre is washed and dressed by Bernadette, who maintains that her husband still has some cognitive function.

“Jean-Pierre feels, smells, hears, jumps when a dog barks. But he cannot see,” his wife said in 2007.

Even after all these years she remains relentless in her support and love for her husband. “I have the feeling that time stopped on 17 March 1982,” Bernadette explained in a discussion with Midi Libre in 2012. “There are no changes, either good or bad. While he does not need respiratory assistance, he remains in a vegetative state.

“Last year, we met a neurologist specialising in brain injury from Carémeau [the hospital in Nîmes] through an acquaintance. He ran his tests and examinations at the hospital, which confirmed very significant damage. There was a lot of damage in the brain. But he does not age, but for a few white hairs.”

Despite confirming that her daily routine is “killing her”, euthanasia is not an option she would consider. “It’s unthinkable!” she said. “He cannot speak. And it’s not for me to decide for him.”

Jean-Pierre, whose son Laurent briefly followed in his footsteps by signing for Nîmes in 1996, is now a grandfather and has been introduced to all of his grandchildren. The rest of the world has moved on, but Adams lives on as a pioneer, whose unlikely journey to prosperity has been replicated by so many since he was sent from Senegal to France as a young boy.