How Five Men Control a Third (37%) of one of Africa’s Largest Exchange – And What It Means for Everyone Else. This OpEd can be read in conjunction with “Ownership Concentration and Market Influence in The Nigerian Exchange (NGX) 2025” for context, in this 6-part review.

Prologue: THE DANCE OF THE ELEPHANTS

On the morning of August 9, 2025, something extraordinary happened in Lagos. For the first time since the Nigerian Stock Exchange began tracking such things, a company owned almost entirely by one man, Abdulsamad Rabiu’s BUA Foods, surpassed Aliko Dangote’s cement empire to become the most valuable stock in Africa’s largest economy.

The shift was more than numerical. It was symbolic. For fifteen years, since Dangote Cement’s blockbuster IPO in 2010, Aliko Dangote had sat atop Nigeria’s equity market like a colossus. His cement company, 87% owned by his holding vehicle, Dangote Industries, was the immovable object, the perpetual #1, the stock that defined the market itself.

But on that August morning, Rabiu’s food conglomerate, itself 90% controlled by family members, closed at a market value of ₦10.35 trillion. Dangote Cement stood at ₦9.74 trillion. The crown had changed heads, though it remained firmly within the same exclusive club: Nigeria’s billionaire industrialists.

MTN Nigeria, the telecom giant 79% owned by its South African parent, ranked third at ₦9.66 trillion. Between these three companies, BUA Foods, Dangote Cement, and MTN – nearly ₦30 trillion in market capitalisation was controlled by corporate vehicles with minimal public float. In dollar terms, roughly $20 billion in ‘publicly traded’ stock that the public could barely trade.

Welcome to the Nigerian Exchange (NGX), where the market capitalisation surged past ₦99 trillion in 2025, and the All-Share Index posted a world-beating 51% return. Beneath the surface, five men effectively controlled more than a third of the show.

This is the story of how concentration became the defining characteristic of Nigeria’s capital market—and why it matters for everyone from pension savers in Lagos to hedge fund managers in London trying to understand what ‘liquidity’ actually means on the NGX.

1: THE ARCHITECTURE OF CONCENTRATION

When 10 Companies Own Two-Thirds of Everything

Let’s start with the numbers, but not in the bloodless way of spreadsheets. Think of the Nigerian Exchange as a party where 160 guests showed up, but ten of them brought so much wine that they now control what everyone drinks, when the music plays, and who gets to leave early.

As 2025 closed, the top ten companies on the NGX commanded a market capitalisation of ₦62 trillion. Total market cap: ₦99.4 trillion. Do the math: 62.4%. The remaining 150+ companies – banks, breweries, paint manufacturers, insurance firms, agribusinesses – shared the remaining 37.6% among themselves like scraps at a feast they didn’t cook.

This isn’t normal. It’s not even close to normal.

The S&P 500, America’s benchmark index and the closest thing global finance has to scripture, sees its top ten companies control 38-40% of total market cap. And analysts are expressing concern about concentration risk THERE. The ‘Magnificent Seven’ tech stocks—Apple, Microsoft, Nvidia, Amazon, and the rest, have triggered existential debates about whether passive index investing has become a rigged game.

Nigeria’s top ten don’t just exceed that threshold. They shatter it. 62.4% is not concentration. It’s domination.

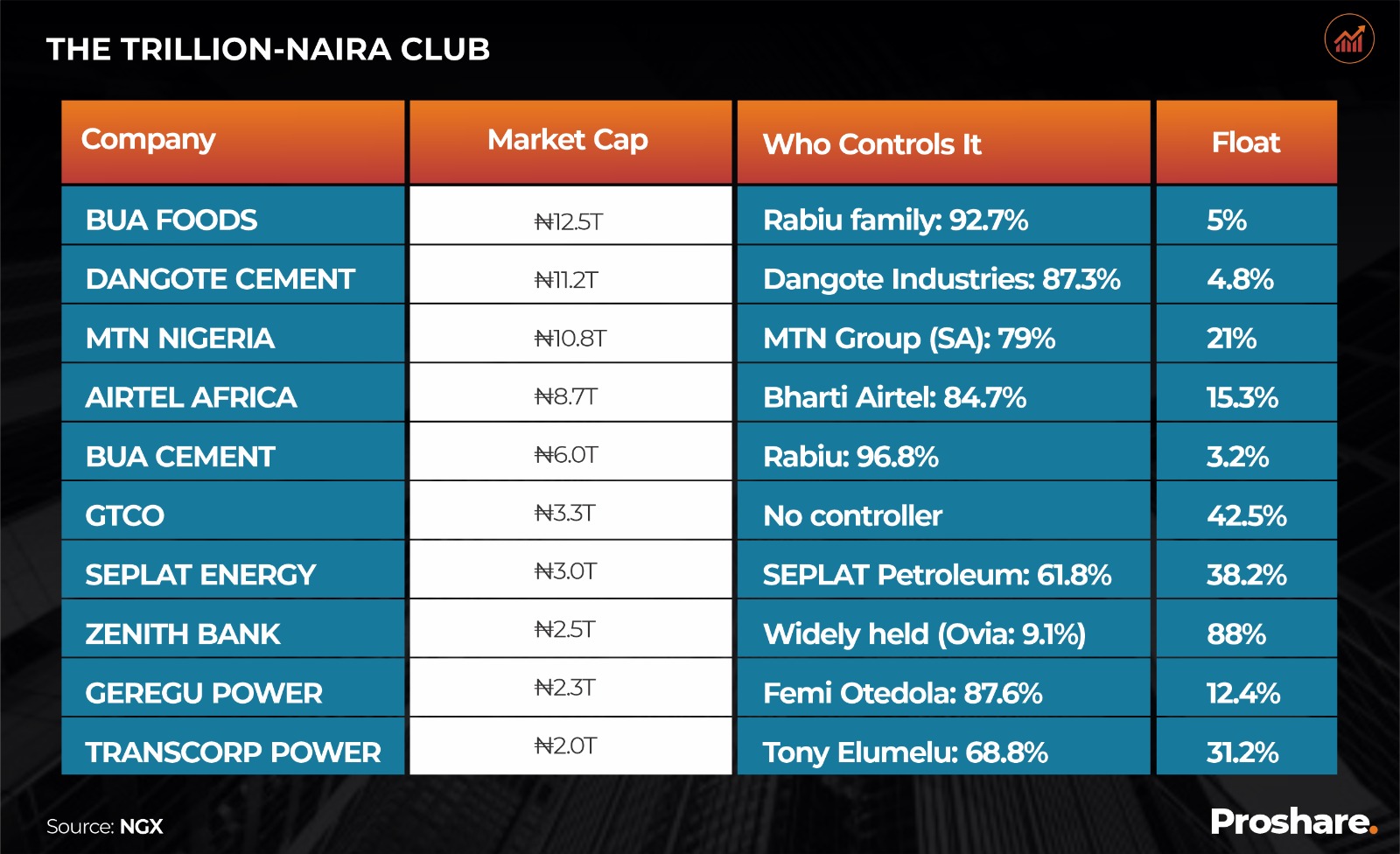

The Trillion-Naira Club

Here’s who made the cut, and more importantly, who CONTROLS them:

Notice anything? Of the top ten, only three – GTCO, Zenith Bank, and Seplat Energy; have free floats above 30%. The rest are locked up tighter than Fort Knox. BUA Cement’s 3.2% free float means that of its ₦6 trillion market value, only ₦192 billion is theoretically available for public trading. The rest? Family office.

Average free float across the top ten: 26.2%. For context, the average S&P 500 company has a free float of around 85%. The difference isn’t just a number. It’s the difference between a liquid market and a private club with a stock ticker.

What Free Float Actually Means and Why It Matters

Free float is the percentage of shares available for public trading – the portion not locked up by founders, governments, or strategic investors. It’s the oxygen of capital markets. Without adequate free float, you don’t have price discovery. You have a price suggestion.

Imagine trying to buy ₦5 billion worth of BUA Foods. With a 5% free float on a ₦12.5 trillion market cap, only ₦625 billion is theoretically tradable. Your ₦5 billion order is 0.8% of the ENTIRE tradable supply. You’re not buying shares. You’re moving mountains.

This is why institutional investors—pension funds, sovereign wealth funds, and endowments – approach the NGX with caution. It’s not that they don’t see the opportunity. Nigeria has 220 million people, a growing middle class, and companies printing cash. The problem is they can’t get in without telegraphing their intentions, and they can’t get out without creating a stampede.

“We wanted to build a ₦20 billion position across the top five NGX stocks. Our traders came back and said it would take six months and we’d move every price by 10-15%. We passed.” — Portfolio Manager, London-based EM Fund (speaking on condition of anonymity)

So, the concentration persists. The billionaires hold. The public trades the scraps. And the market, for all its headline gains, remains fundamentally illiquid at the top.

2: THE FIVE KINGS

Abdulsamad Rabiu: The Quiet Conqueror

If you ask most Nigerians to name the country’s richest man, they’ll say Aliko Dangote. They’d be wrong, at least as of late 2025. Abdulsamad Rabiu, the 64-year-old chairman of BUA Group, controls companies worth ₦17 trillion on the NGX. Dangote’s listed holdings? ₦9.8 trillion. The gap isn’t close.

Rabiu built his empire in the shadows of Dangote’s spotlight, which suited him fine. While Dangote courted presidents and commissioned the world’s largest single-train oil refinery, Rabiu quietly integrated vertically. Sugar. Flour. Pasta. Rice. Edible oils. Cement. The staples of Nigerian life, all flowing through BUA-controlled supply chains.

When BUA Foods was listed in January 2022 at a ₦720 billion valuation, sceptics questioned whether the market could support two food giants (Dangote’s Dangote Sugar and NASCON were already publicly traded). By August 2025, BUA Foods hit ₦10.35 trillion. The sceptics went quiet.

What makes Rabiu’s dominance particularly striking is how little he shares. BUA Foods: 89.9% family owned. BUA Cement: 96.8%. Combined, the Rabiu family controls ₦17 trillion in market value and offers the public less than 5% participation in either company.

“We believe in building for the long term. Short-term market pressures don’t drive our decisions. We’re not here to trade shares; we’re here to build businesses.” — Abdulsamad Rabiu, BUA Group (2024 interview)

Translation: This is my company. You can watch.

Aliko Dangote: The Emperor Dethroned but Still Reigning

Aliko Dangote doesn’t do second place well. For fifteen years, Dangote Cement held the #1 position in Nigeria’s market-cap rankings. It wasn’t just a stock; it was a monument. At its 2010 IPO, it raised ₦135 billion and immediately became the largest company on the exchange. By 2014, it accounted for 20% of the entire NGX market capitalisation.

Then BUA Foods happened. Then MTN surged. By December 2025, Dangote Cement ranked second at ₦11.2 trillion, still massive, still profitable, no longer the singular gravitational force it once was.

Yet Dangote’s grip remains unshakeable. Dangote Industries Limited owns 87.3% of Dangote Cement. The remaining 12.7%? Mostly held by institutional nominees such as Stanbic IBTC, which are often held on behalf of… we don’t always know. The free float is 4.8%. In effect, this is a private company with a public ticker symbol.

Dangote’s Pan-African vision is real, with cement plants in 12 countries, 52 million tonnes per annum capacity, and subsidiaries in Cameroon, Ghana, Ethiopia, Senegal, South Africa, Tanzania, and Zambia. The $20 billion Dangote Refinery, which finally began operations in 2023, processes 650,000 barrels per day.

But here’s the thing about Dangote’s empire: it’s VERTICALLY INTEGRATED and PRIVATELY HELD at the core. Dangote Cement is the public face, but the real action happens upstream in Dangote Industries, the unlisted holding company that controls everything. Minority shareholders in Dangote Cement get to ride the wave, but they don’t get to steer the ship.

In late 2025, Bloomberg estimated Dangote’s net worth at $13.9 billion, making him Africa’s richest individual. Most of that wealth is locked up in private holdings. The listed stocks? Just the tip of the iceberg.

Jim Ovia: The Banker Who Built a Monument

Jim Ovia is different from Rabiu and Dangote in one critical way: he doesn’t control his company. Not in the way they do.

When Ovia founded Zenith Bank in 1990 with $4 million in startup capital, Nigeria’s banking landscape was dominated by four giants: Union Bank, First Bank, UBA, and Afribank. They were old money, government-connected, complacent. Ovia was none of those things.

By 2004, Zenith went public. By 2007, it was Nigeria’s largest bank by assets. By 2025, it commanded a market capitalisation of ₦2.5 trillion and an 88% free float – the highest among the top ten NGX stocks.

Ovia’s 9.1% stake is valued at approximately ₦227 billion, making him a very wealthy individual. But unlike Rabiu (90% ownership) or Dangote (87% ownership), Ovia DOESN’T control Zenith in the traditional sense. He’s the largest individual shareholder, yes. He’s the founder and chairman, yes. However, 88% of the company’s shares trade freely.

This distinction matters. When BUA Foods or Dangote Cement makes a strategic decision—acquire a rival, invest billions in new capacity, restructure debt—one man and his inner circle make the call. When Zenith Bank makes a strategic decision, it goes through a board with independent directors, institutional shareholders, and actual governance structures.

Ovia’s H1 2025 dividend: ₦7.25 billion, a 64% increase year-over-year. Not bad for a founder who chose to share rather than hoard.

“We built Zenith to serve Nigeria, not to enrich a family. The market has rewarded that philosophy.” — Jim Ovia, Founder & Chairman, Zenith Bank

Ovia represents what the NGX could be if more founders followed his lead. But they haven’t, and they won’t—not without incentives or pressure to do so.

The Supporting Cast: Otedola, Elumelu and the Second Tier

Beyond the Big Three, two names deserve mention: Femi Otedola and Tony Elumelu.

Otedola, the energy magnate, owned 87.6% of Geregu Power (₦2.3T market cap) before selling it in a year-end exit that ranks among Nigeria’s most significant private equity transactions.

Billionaire Femi Otedola sold his controlling 95% stake in Amperion Power Distribution Company, Geregu Power’s majority shareholder, to MA’AM Energy Limited for an estimated ₦1.088 trillion ($750 million) in a deal that closed December 29, 2025, effectively transferring control of 77% of Geregu Power Plc, the NGX-listed independent power producer valued at ₦2.853 trillion.

The transaction, financed by a consortium of Nigerian banks led by Zenith Bank with Blackbirch Capital advising, represents a masterclass in timing: Otedola acquired Geregu during the chaotic 2013 power privatization when most investors fled, rode an extraordinary 400%+ stock surge between 2023-2025 as Nigeria’s electricity crisis made private generation highly profitable, and exited at peak valuations to MA’AM Energy, an Abuja-based integrated energy firm.

Critically, the sale occurred at the holding company level (Amperion) rather than through direct NGX share transfers, meaning Geregu’s public float structure remains technically unchanged even as ultimate beneficial ownership shifted entirely, a structure that allowed Otedola to monetise his position without triggering a mandatory tender offer to minority shareholders or causing market disruption. Minority shareholders are unhappy with this.

The deal underscores both the maturation of Nigeria’s power sector (now attractive enough to command billion-dollar valuations) and the liquidity constraints of the NGX: even a billionaire selling a ₦2+ trillion stake must execute off-exchange through holding company structures rather than via the public market, highlighting the concentration and illiquidity themes that define Nigeria’s capital markets.

Elumelu, the Pan-African investor, controls Transcorp Power through his Heirs Holdings conglomerate and UBA shareholdings – 68.8% ownership and a ₦2 trillion market capitalisation. Like Otedola, he bet on power when others doubted. Unlike Otedola, Elumelu’s empire stretches beyond energy: banking (UBA across 20 African countries), real estate (Transcorp Hilton), and oil & gas.

In a landmark validation of his “Africapitalism” philosophy, Tony Elumelu’s Heirs Energies completed a transformative $500 million acquisition on December 31, 2025, purchasing French energy firm Maurel & Prom’s entire 20.07% stake (120.4 million shares) in Seplat Energy Plc at £3.05 per share, catapulting Heirs Energies to become Seplat’s largest single shareholder ahead of institutional investors like Petrolin Group (13.77%) and Sustainable Capital (9.7%). Financed entirely by African development finance institutions – Afreximbank and Africa Finance Corporation (AFC), just one week after Heirs secured a separate $750 million Afreximbank facility.

The transaction represents a watershed moment demonstrating that African capital can finance African development at scale, the core tenet of Elumelu’s Africapitalism thesis that local investors, not Western multinationals, should control Africa’s strategic assets.

While the 20.07% stake is influential rather than controlling, it positions Heirs Energies as the anchor investor in one of Africa’s premier independent oil producers, a company with operations across Nigeria’s prolific Niger Delta, production exceeding 50,000 barrels per day, and dual listing on both the Nigerian Exchange and London Stock Exchange.

It offers strategic possibilities, including board representation, operational collaboration, and potential future consolidation in Nigeria’s fragmenting upstream sector as IOCs continue their retreat.

The deal, coming barely 18 months after Heirs’ $430 million ExxonMobil shallow-water acquisition, cements Elumelu’s energy conglomerate as a dominant indigenous player and demonstrates that African capital markets, when mobilised through patient institutional lenders like Afreximbank, can execute transactions historically reserved for Western oil majors and Chinese state entities.

Together, Rabiu, Dangote, Ovia, Otedola, and Elumelu control or significantly influence companies worth ₦37 trillion – 37% of the entire NGX. Five men. More than a third of Africa’s largest stock market.

This isn’t capitalism. It’s an oligopoly with a stock ticker.

3: THE LIQUIDITY MIRAGE

When Markets Look Liquid but Are Not

Here’s a question that keeps institutional investors awake at night: If a stock trades ₦2 billion a day, and you want to buy ₦10 billion, how long does it take?

The textbook answer: Five days, assuming you absorb all available liquidity. The real answer on the NGX: Six months to a year, assuming you don’t want to move the price by 20%.

This is the liquidity mirage. NGX’s daily trading volume averaged ₦24 billion in 2025, approximately $16 million at year-end exchange rates. For comparison, the S&P 500 trades roughly $500 billion daily. That’s a 31,000-to-1 ratio.

But raw volume numbers don’t tell the whole story. What matters is WHERE that volume concentrates. On a typical trading day, 60-70% of NGX volume comes from just 15-20 stocks. Within those stocks, much of the trading is by retail investors moving between ₦100,000 and ₦5 million, a pattern that defines mature markets.

When a foreign pension fund wants to deploy $50 million into Nigeria, they face an impossible choice:

- Option A: Buy the liquid banks (GTCO, Zenith). Problem: You’re now overweight in financial services and underexposed to Nigeria’s consumer growth story.

- Option B: Buy BUA Foods and Dangote Cement to capture consumer and infrastructure themes. Problem: Combined 5% float means your $50M moves markets violently.

- Option C: Spread across 30 stocks. Problem: Most are illiquid micro-caps with governance issues.

So, they often choose Option D: Don’t invest at all. Nigeria remains perpetually ‘underweight’ in emerging market portfolios, not because investors don’t believe in the story, but because they can’t execute the trade without becoming the story.

The Float Trap

Low float creates a vicious cycle that reinforces itself:

- Founder holds 90% → Only 10% trades → Price discovery weak → Volatility high.

- High volatility → Institutional investors avoid → Demand stays retail dominated.

- Retail-dominated market → Founder sees no reason to dilute → Float stays at 10%.

- Repeat forever.

Breaking this cycle requires either regulatory mandates (e.g., minimum float requirements for listings) or market incentives (e.g., lower fees and tax breaks for companies that expand free float). Neither has materialised.

Instead, Nigerian founders have internalized a different philosophy: ‘Why give up control when I don’t need the capital?’ BUA Foods raised ₦720 billion IPO in 2022. Rabiu COULD have sold 30-40% of the company and still maintained control with 60%. He chose 5% float instead. The message: This listing is for valuation and prestige, not capital raising.

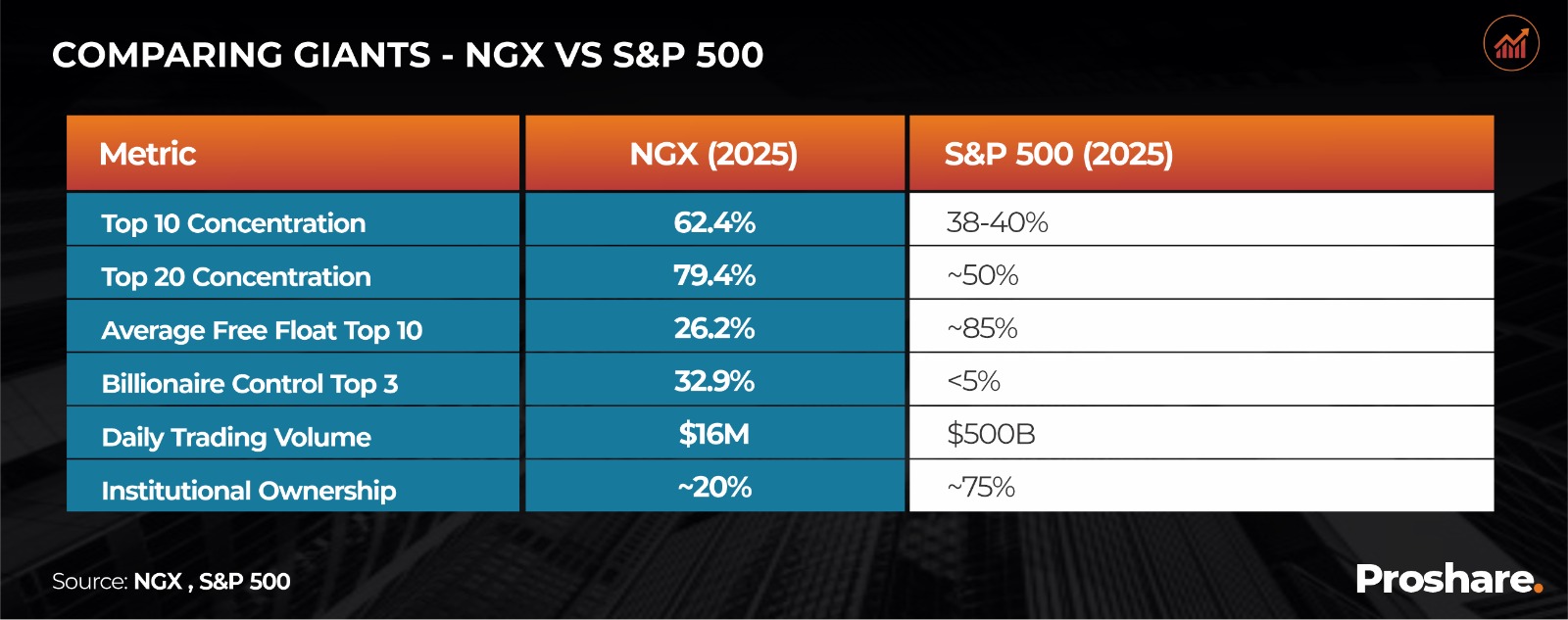

4: COMPARING GIANTS – NGX VS S&P 500

Two Markets, Two Philosophies

The S&P 500 has its own concentration problem. As 2025 opened, the ‘Magnificent Seven’ tech stocks—Apple, Microsoft, Nvidia, Amazon, Alphabet, Meta, Tesla—accounted for roughly 30% of the index. The top 10 companies controlled 38-40% of total market cap, the highest since the dot-com bubble.

Scott Galloway, the NYU marketing professor turned market commentator, wrote in October 2025: ‘The top 10 stocks in the S&P 500 account for 40% of the index’s market cap. Since ChatGPT’s launch, AI-related stocks have accounted for 75% of S&P 500 returns. This concentration creates fragility.’

He’s right. But here’s what Galloway and other American analysts miss when they panic about S&P concentration: The NGX makes the S&P 500 look like a socialist commune.

Source: NGX , S&P 500

The differences are stark. The S&P 500’s concentration is PERFORMANCE-driven: tech stocks have grown in dominance because they deliver earnings and returns. Nvidia’s 7.5% index weight exists because it prints $60 billion in annual net income, not because Jensen Huang refuses to sell shares.

The NGX’s concentration is STRUCTURAL and OWNERSHIP-driven: Rabiu and Dangote control 30%+ of the market not through superior returns (though their companies perform well), but through REFUSAL TO SHARE. Their listed entities ARE their private empires.

The Governance Gap: The other critical difference: governance.

In the S&P 500, the largest shareholders are Vanguard, BlackRock, and State Street—index funds that collectively own 15-20% of most major companies. These institutions vote on director elections, executive compensation, major M&A, and capital allocation. When a CEO proposes a questionable acquisition, these giants can and do vote ‘no.’

On the NGX, the largest shareholders are often the CEOs themselves (or their family holding companies). When Rabiu wants BUA Foods to enter a new business line or acquire a competitor, there’s no meaningful check. He IS the board, the management, and the controlling shareholder.

This creates related-party transaction risks that would horrify American institutional investors. Dangote Cement buys clinker from Dangote Group entities. BUA Foods sources raw materials from BUA Group companies. The prices are ‘market-based,’ sure—but who audits the market when you control both sides?

5: WHAT IT ALL MEANS

For Investors: Navigate or Exit

If you’re reading this with money to deploy, here’s the bottom line: The NGX is investable, but you must accept its constraints.

DO:

- Focus on the three high-float stocks (GTCO, Zenith, Seplat). You can build and exit positions without moving markets.

- Use rights issues as entry points. Nigerian banks are recapitalising through Q1 2026, offering fixed-price entry windows.

- Accept currency risk as part of the deal. The naira depreciated by 68% from 2023 to 2025. Even with 51% index gains, dollar-adjusted returns are more modest.

- Try to build significant positions in founder-controlled stocks (BUA, Dangote). You’ll move prices before you’re halfway done buying.

- Assume governance protections. You’re a minority shareholder in billionaire-controlled entities. Know what you’re signing up for. MI’s in Geregu found out the hard way.

For Nigeria: Reform or Stagnate

Nigeria’s capital market has delivered. 51% returns in 2025. N36.5 trillion in wealth creation. Banks raised N6.34 trillion in fresh capital. By any measure, the NGX had a banner year.

But here’s the uncomfortable truth: Nigeria’s equity market is too small, too concentrated, and too illiquid to finance the country’s $1 trillion GDP ambitions.

The top 20 companies are worth a combined $54 billion. Nigeria’s infrastructure deficit alone is estimated at $100 billion. The math doesn’t work.

- Minimum Float Requirements: Mandate 25-30% free float for premium board listings within 5 years.

- Pension Fund Reform: Allow Nigerian pension funds to invest MORE in equities, but ONLY in stocks with adequate liquidity (30%+ float).

- Governance Strengthening: Independent directors, mandatory disclosure of related-party transactions, and minority shareholder protections with teeth.

- New Sector Development: Fintech, healthcare tech, renewable energy—new industries with dispersed ownership from inception.

- Tax Incentives: Lower capital gains tax for individual investors in high-float stocks. Make liquidity provision economically attractive.

Will any of this happen? That is unclear at this time, but many people, including the billionaires mentioned here, are considering it. That is a good sign.

The billionaires who control the market, however, have no incentive to dilute. The regulators lack the political will to force them. And retail investors, for now, are content to ride the wave.

6: EPILOGUE: THE NEXT CHAPTER

On December 31, 2025, the Nigerian Exchange closed at 155,613 points, the highest in its history. Champagne corks popped up at brokerage firms across Lagos. Fund managers sent congratulatory emails to clients. The headlines wrote themselves: ‘NGX Posts World-Beating Returns.’

And it’s all true. By any conventional metric, 2025 was a triumph.

But as the new year dawned, three men – Abdulsamad Rabiu, Aliko Dangote, and Jim Ovia, woke up controlling a third of Africa’s largest stock market. The concentration that defined 2025 would define 2026, and likely 2027 and 2028. Femi Otedola and Tony Elumelu are writing their playbooks even as we write ours. It is a new gameplay going forward.

Here’s the thing about oligopolies: They’re stable. They’re profitable. And they’re incredibly hard to dislodge.

The question facing Nigeria is not whether the NGX can deliver returns; it clearly can. The question is whether it can evolve into the deep, liquid, diversified capital market that a $1 trillion economy requires.

Right now, the answer is no, but the spotlight has been shone on capital flows. This analysis will be due for review by year’s end, provided that all goes according to the fiscal and monetary plans designed to support local investment in the economy.

To support the optimism that the story isn’t over, somewhere in Lagos, a fintech startup is building a payments platform that could become the next ₦5 trillion company. Somewhere in Abuja, a regulator is drafting new float requirements. Somewhere in Kano, an entrepreneur is planning an IPO that will break the billionaire mould.

The NGX’s next chapter will be written by whether these forces prevail, or the billionaire’s exchange remains precisely that: a market where three men hold the keys, and everyone else pays for admission.

Stay ahead with the latest updates!

Join The Podium Media on WhatsApp for real-time news alerts, breaking stories, and exclusive content delivered straight to your phone. Don’t miss a headline — subscribe now!

Chat with Us on WhatsApp