By Sultan Quadri

In March, product designer, Ibrahim*, and his friends cancelled plans to travel from Kaduna to Abuja by rail because they suddenly didn’t feel up to it. Later that month, on the 28th, when they had been scheduled to go, armed bandits attacked a train on the route they were supposed to take. Ibrahim was left shaken. Just two days before that train attack, an assault by armed bandits on the Kaduna International Airport had left at least one person dead.

Nigeria has been struggling to keep its citizens safe in the past decade, as rising insecurity sweeps the country. Data from the TheCable Index shows that 1,743 Nigerians were killed in the first quarter of the year as a result of insecurity.

The train attack rightly caused Ibrahim to fear for his safety in Nigeria, and he began to make plans to leave the country. His family was in support. They told him he could get a better job and live the life he couldn’t live in Nigeria abroad.

Ibrahim moved to the UK last month. He is one of many middle-class and highly skilled individuals leaving the country to escape ever-rising insecurity, inadequate infrastructure, insufficient social amenities, a deplorable economy, and scarce employment opportunities.

“Nigeria has almost killed me many times,” Ibrahim lamented, recalling that he once developed a stomach ulcer after a doctor at a Lagos hospital put him on aspirin for a month.

What is perhaps unique about the latest migration wave is that it significantly affects the nascent tech ecosystem in Nigeria. Between 2014 and 2021, 474 Nigerian tech talent moved to the UK via the UK government’s Tech Talent Visa, a visa that allows tech talent to work in the country’s digital technology sector.

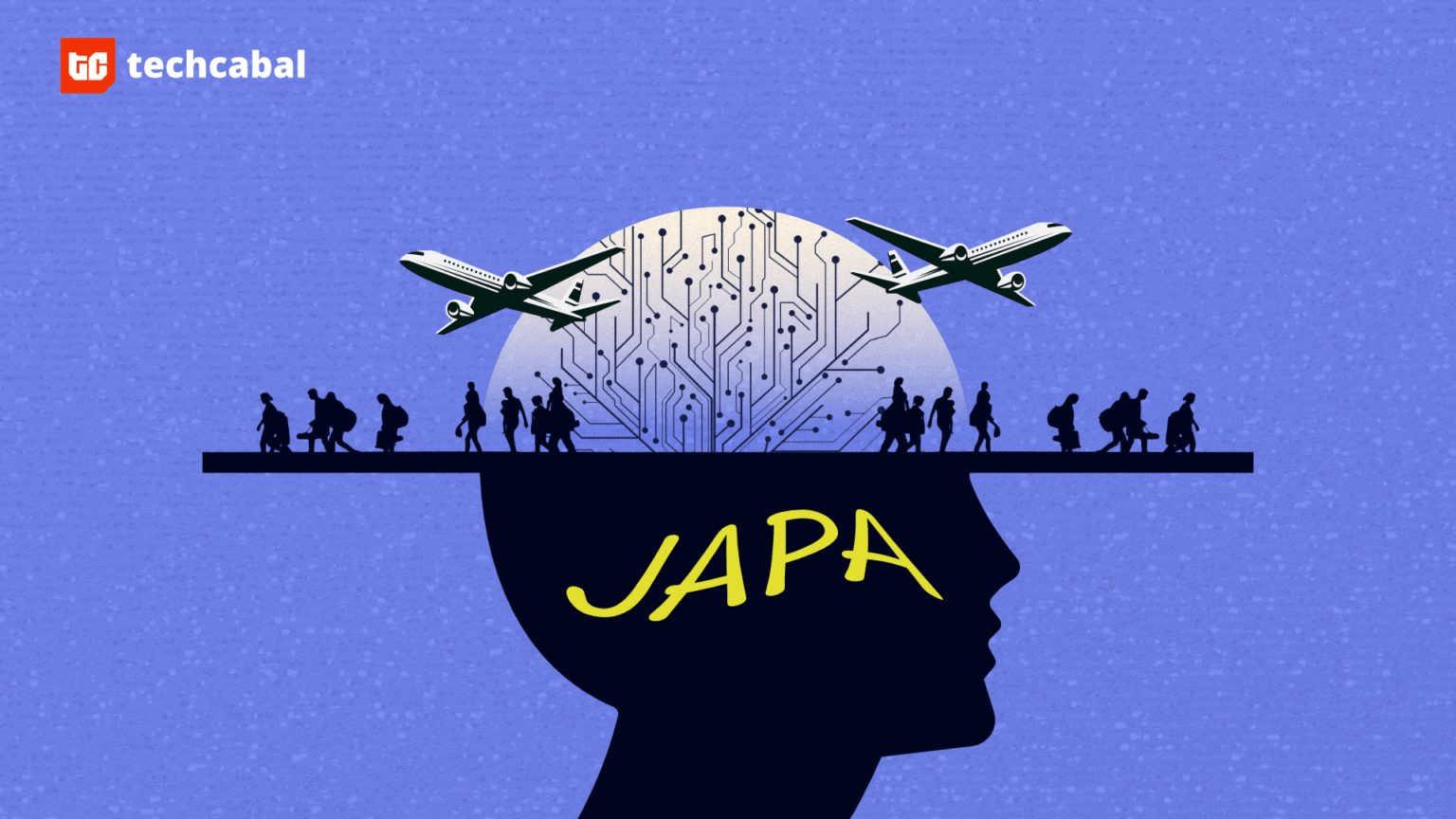

“Japa”, a popular slang in Nigeria for brain drain—the movement of skilled workers out of a country—is an ongoing conversation in Africa’s largest market, with hordes of doctors emigrating, and the number of students going overseas for their education doubling between 2015 and 2022.

Nigeria has the largest population on the African continent, boasting a headcount of 200 million people. Some 35% of its population is unemployed, and the working population that supports the country’s $450 billion economy are leaving in droves.

In the past few years, interest in the Nigerian tech economy has increased and more investors are willing to pump money into startups that are based in the country and that serve its population. In the same vein, global firms are looking at the country’s growing tech industry to fill their talent gaps. Consequently, the country’s tech ecosystem has found itself groaning as the talent that is supposed to support this growing ecosystem is bleeding out.

Global aspirations

In July 2019, Hope Oluwalolope, then in her final year at the University of Lagos, began applying to Big Tech and Fortune 500 companies as a software engineer. She faced numerous rejections.

Months later, after graduating with a first-class degree, she received an offer to join Microsoft as a software developer in Canada in December 2019. Because she was still in school when she applied for the role, she took a year buffer, but the pandemic and visa issues meant she couldn’t join the team until February 2021.

Hope’s choice of Microsoft’s talent pipeline had been influenced by her ambition to work with a global company, but she wasn’t keen on leaving Nigeria for that. Unfortunately, Microsoft didn’t have a Nigerian office in 2019. It wasn’t until March 2022, a year after Hope had moved to Canada, that the company opened its African Development Centre in Lagos.

For Obinna Ekwuno, a developer advocate at Cloudflare who moved to the UK last year, leaving the country had always been an open conversation. Ekwuno had always wanted to work at a global level, and while on short visits to Dubai and London, he realised that moving abroad would expose him to opportunities to do so.

“The push [to leave] is wanting more for yourself and trying to get that opportunity to be able to show that you can compete on this scale, and show the world that Nigeria as a nation isn’t just filled with some dumb scammers. It’s just being able to represent and change the narrative,” Ekwuno told TechCabal.

Relocating abroad has brought Ekwuno peace of mind. Back in Nigeria, he had experienced the #EndSARS protests against police brutality, which led to the violent murders of tens of young Nigerians by the Nigerian army on October 20, 2020. The traumatising event eventually gave him the final push to permanently immigrate.

For example, Ekwuno is not scared to leave his house with his laptop as he is not afraid of being stopped by the police on suspicion of being a fraudster. It is common for the Nigerian police to harass road users, especially young men, about the source of their livelihood simply for owning basic devices like phones and laptops.

“As humans, our scale of needs is, if you can eat and you can sleep and you feel safe, then you can build. For Lagosians or Nigerians in general, it’s like we are doing all of that and at the same time fighting for our lives and also fighting for creative expressions,” Ekwuno said.

Creating a supportive environment

The current brain drain bears a close resemblance to that of the 1980s. After enjoying an economic boom from oil, Nigeria suffered a downturn and thousands of skilled workers—a large number of them doctors—and middle-class citizens left the country to fill workforce gaps in North America and Europe.

Rasheeda Seghosime, COO of Africa Foresight Group (AFG), a talent recruitment startup that connects freelance management consultants to African businesses, found that many of the workers leaving the country are people who are employed but not paid their worth.

“The people that are leaving are not those that have no jobs. You find all sorts of people across banks, telcos and consulting firms leaving, and that’s because there is also a large element of underpayment,” Seghosime told TechCabal from her Accra residence.

To tackle this, Seghosime said that AFG brings top opportunities to its pool of freelancer workers without them having to leave their home countries. AFG, which intends to train 250,000, also offers a pipeline for fresh graduates and early-career professionals from different fields to become business analysts.

“We always have a constant flow of talent joining our pool, because even though the gig economy is so big globally, when it comes to the continent, it hasn’t quite caught on yet. We cannot depend on traditional forms of recruiting to get talent,” she explained. “We help talent to realise that this is a great opportunity for them, that we’re willing to give them the training they require, and give them the support that they also need to exist.”

AFG’s model is one of few models that exist to create a supportive talent for home-based talent. Sure, the hurdles are many, but with more innovative working arrangements like this, more highly skilled people might lose their motivation to leave the country.

A necessary evil

According to research, brain drain in developing countries can be both beneficial and harmful. While it harms the skill structure of the labour force and results in a labour shortage, it also helps to generate huge remittance flow from those abroad—$19.2 billion last year—and allows returnees to bring their skills, business network, and innovation home.

Sultan Akintunde, co-founder of AltSchool and TalentQL, sister companies that are training entry- to senior-level developers and placing them in international companies, believes that talent immigration is a necessary evil. Akintunde highlighted that the founders of the biggest tech companies in the country, including Flutterwave, Kuda and Interswitch, have, at one point or the other, lived or worked outside the country.

“Let people travel, make money, connection and partnerships, have access and learn new technologies. It’s useful to the ecosystem. You can’t build global talent by locking them up locally,” he posited.

For him, this wave of tech talent migration in Nigeria is also fuelled by global companies that are increasingly turning to Nigeria to satisfy their talent needs because they need functional expertise for when they want to penetrate the market.

Nigeria’s tech ecosystem was visibly unsettled when Amazon announced an interviewing event from August 1–5 to attract some of its best workers to relocate to its offices in the US, Canada, and Ireland. Ngozi Dozie, the co-founder of Nigerian neobank, Carbon, even tried to discourage developers from attending Amazon’s event plans by urging founders of Nigerian tech companies to host a celebration of technical talent in the country.

In the past few years, Microsoft and Amazon have instituted new hiring programmes that see them relocate Nigerian developers to Canada, the US, and Ireland.

Another reason Akintunde gave for why tech talents are migrating is to bypass the restrictions of the Nigerian passport.

“I had a fully-paid trip to the US for a conference in 2018, but I couldn’t get my visa. If I had been living in the US, it would have been easier for me to attend. You don’t want it to get to a point whereby you need to urgently travel before making such preparations.”

For Akintunde, the real problem is that the country does not have enough tech talent, not that tech talent is leaving. When framed this way, the solution looks more like training new talent rather than groaning over the necessary evil.

For context, tech recruitment firm Tunga reports that there are only 114,536 software developers in Nigeria, a country with 200 million people and a 35% unemployment rate. That figure is measly compared to the 630,000 developers that the state of California has even with its 39 million population.

“The ripple effect [of people leaving] is that people will make more money and come back to build new companies and or become CEOs of their companies. An example is how more than half of the Big Tech companies in the world have Indian CEOs. They didn’t become CEOs by staying in India,” Akintunde ended.

Not everyone shares the same sentiment about coming back to the country to build. Some of the emigrated workers TechCabal spoke to cited Nigeria’s uncertain regulatory climate and whiplash policies as concerns discouraging them from returning to the country as investors and co-founders.

As Nigerian startups receive money from investors to build high-growth startups, they will struggle with finding top talent to build them. What this means is that tech talent training and recruitment companies have their work cut out for them. On the upside, those leaving are making more room for the underemployed and unemployed to move into tech and become top talent too.

*Name changed to protect source’s identity.

Techcabal

Stay ahead with the latest updates!

Join The Podium Media on WhatsApp for real-time news alerts, breaking stories, and exclusive content delivered straight to your phone. Don’t miss a headline — subscribe now!

Chat with Us on WhatsApp