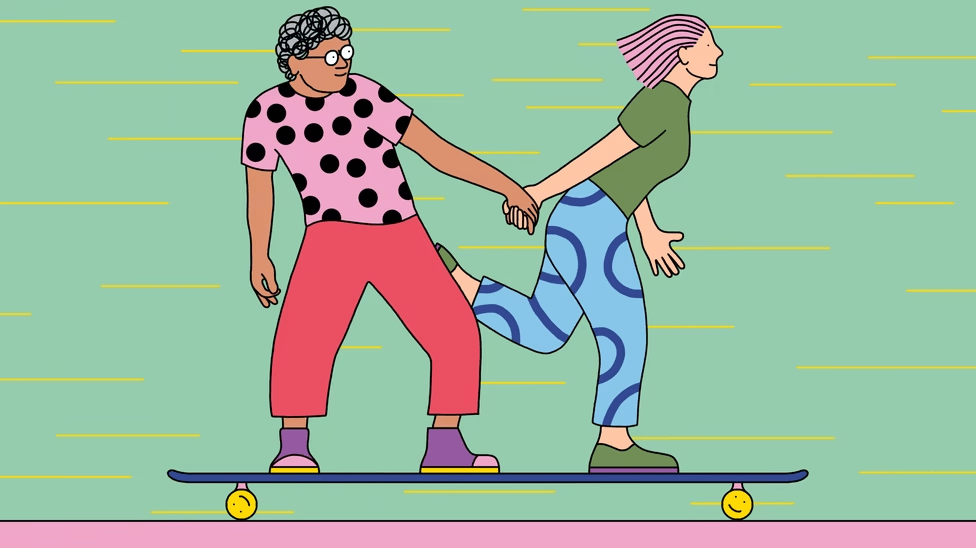

Approach disagreements with your partner not as a “me,” but as a “we.”

elebrity news doesn’t typically interest me, but a quote from the actor Scarlett Johansson recently caught my eye. The 37-year-old has been married three times, and in an interview, she gave her assessment of why so many celebrity marriages seem to fail. The reason she cited from firsthand experience wasn’t being too busy, or apart too much, or filming sex scenes with someone who isn’t your spouse. “If one person is more successful than the other,” she noted, “there may be a competitive thing.”

It’s easy to see how competition could wreck a marriage when millions of dollars and adoring fans are at stake. But the rest of us really aren’t so different. We all have individual interests that are important to us, and they can readily fester into competition in a relationship. Small things such as who unloads the dishwasher can become a contentious issue of fairness; when one partner earns more money than the other, it can stimulate rivalry even between people in love.

As a man who has been married for the past 31 years, I know this is natural. But competition doesn’t have to be the predominant language of a relationship, nor should it be. The most harmonious couples are the ones who learn to play on the same team. Their predominant mode of interaction is collaborative, not competitive.

Few people, I imagine, enter into a romantic union seeing it explicitly as a competition. “I’m going to kick his butt” doesn’t make for a great wedding vow. However, this is effectively what happens when each partner prioritizes “I” over “we,” creating a clash between two identities, according to scholars writing in the journal Self and Identity. In contrast, couples who see themselves as part of a unique couple identity—where neither partner’s individual identity is dominant—tend to be better at coping with conflict. This makes sense: Good teams see internal strife as a problem to solve together, because if unresolved, it lowers the whole team’s morale and performance.

The key is not to eradicate all competition, but to change what kind of competition we’re engaging in. A study of young basketball players published in 2004 in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology makes this clear. Researchers asked a group of boys to shoot free throws. They found that when boys cooperated to get the most free throws as a team and competed against other teams, both their performance and enjoyment were higher than when they competed individually without the support of a cooperative relationship. The implication for love is clear: The world can be harsh and competitive, so face it together—arm in arm. Your partner’s struggles are your struggles, and their victories are your victories. Your adversaries are the problems you both face.

Competitive personal relationships are like a prisoner’s dilemma, a famous model in which two partners in crime are motivated only by self-interest. Call them Bonnie and Clyde. If, when captured and interrogated separately by the police on suspicion of bank robbery, Bonnie and Clyde look out only for themselves, they have an incentive to rat out the other to get off easier—but both will lose and go to jail. As researchers have shown, however, if Bonnie and Clyde both independently seek the best outcome for the team (staying silent) rather than what’s good for themselves (squealing), they receive the smallest punishment collectively and the greatest number of years free to be together. I certainly hope your romance does not involve bank robbery, but the lesson is the same: In a competitive relationship, each partner looks out for her or his own interest, and both sides end up getting less than they want and feeling aggrieved. When both sacrifice individually for the joint good of the couple, both are better off.

“Sacrifice” implies loss, but a collaboration can feel like a win to both people. For instance, when it comes to purchasing decisions, such as buying a car, psychologists have found that if both partners cede some control in service of a mutual decision, it doesn’t feel like anyone loses. On the contrary, both partners tend to come away from those decisions feeling a greater sense of power in and satisfaction with the relationship. In my experience, this approach works for all kinds of decisions. For example, I know partners who come out of graduate school together who—instead of moving where one person will have the higher-paying and more prestigious job—resolve to go where their combined income and job satisfaction is highest.

This approach also makes inevitable conflict less harmful to a relationship. All couples have disagreements, but the happier ones frame them as shared problems to manage jointly. Those that have a competitive conflict style (associated with win-lose arguing) tend to be unhappier in their marriage than those with a collaborative conflict style (where the couple works together to find solutions). This pattern is clear even in the way they speak. Researchers studying couples’ arguments have found that those that use “we-words” when they fight are apt to have less cardiovascular arousal, fewer negative emotions, and higher marital satisfaction than those that use “me/you words.”

If your relationship is a little too competitive and not collaborative enough, there are a few effective steps to consider.

1. More we, less me.

We often assume that our thoughts and emotions control what we say, but a lot of research shows the opposite as well: What you choose to say can affect your attitude through the “As-If Principle,” in which acting as if you feel something can induce the brain to make it so. If you want your partnership to be more about “we” than “you versus me,” start making a joint effort to talk that way. Instead of saying, “You don’t try to understand my feelings,” try, “I think we should try to understand each other’s feelings.” Make we your default pronoun when talking with others. If you like staying out late, but your partner hates it, say, “We prefer not to stay out so late” when you turn down a 10 p.m. dinner for your partner’s sake.

2. Put your money on your team.

Many couples act individualistically when it comes to their money—keeping separate bank accounts, for example. This is generally a missed opportunity to think and act as a team. Indeed, scholars have demonstrated that couples that pool all their money tend to be happier and more likely to stay together. This might be harder for partners with very different spending habits. But research has shown that people tend to spend more practically when they pool their resources.

3. Treat your fights like exercise.

Something every inveterate gym-goer will tell you is that if you want to make fitness a long-term habit, you can’t view working out as punishment. It will be painful, sure, but you shouldn’t be unhappy about doing it regularly, because it makes you stronger. For collaborative couples, conflict can be seen in the same way: It’s not fun in the moment, but it is an opportunity to solve a problem collaboratively, which strengthens the relationship. One way to do this is to schedule time to work through an issue, rather than treating it like an emotional emergency. Look at a disagreement as something we need to find time to fix, instead of me being attacked by you, which is a disturbing emergency.

One final note to consider as you work toward greater collaboration in your relationship: This does not mean losing your identity. Collaboration requires people to choose to work together, not to cease being individuals. There is no “us” when one or both lose the self. “The biggest danger, that of losing one’s own self,” wrote the philosopher Søren Kierkegaard, “may pass off as quietly as if it were nothing; every other loss, that of an arm, a leg, five dollars, a wife … is sure to be noticed.” It is, he believed, the basis of despair—certainly not of conjugal bliss.

In love, collaboration brings happiness when it is the ultimate expression of mutual freedom—the decision of each partner to blend the “I” into the cosmic “we” that, almost like magic, expands our happiness beyond what either of us could imagine alone.

Credit: www.the atlantic.com