After a painting stopped him in his tracks, the singer asked 13 artists to create a work for each track of The Evil Genius. It has been, he says, ‘the most therapeutic journey’ – and it’s on show in London

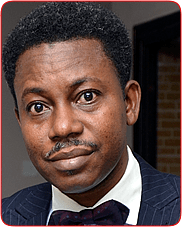

Ask any Afrobeats fan who Mr Eazi is and they’ll probably start smiling. With eyes half closed, they’ll lean back into the dialled-down sound that first brought this Nigerian superstar to global attention, and they’ll probably start singing: “It’s your boy Eazi.”

Mr Eazi is all vibes. Radio 1Xtra’s DJ Edu remembers being in the crowd the first time Eazi played London. Edu says: “It was such a spiritual connection, such a vibe between the crowd and his music and him.” Edu thought, “Wow, there’s definitely something here.”

That was 2017. This year has already seen Eazi launch a new band with Edu, ChopLife SoundSystem, and release their first mixtape, Chop Life, Vol 1: Mzansi Chronicles. And this month marks the release of The Evil Genius, which is billed as Eazi’s first album. It’s exactly not the debut that that phrase usually connotes. Eazi has, after all, done a lot since his first mixtape in 2013. Two more mixtapes; a suite of instant-classic singles (Bankulize, Hollup, Pour Me Water, Leg Over); collabs with everyone from Beyoncé to Burna Boy that have netted him a Grammy; and entrepreneurial coups that put him on Forbes Africa’s “30 under 30” list.

The first time we speak, it’s via Zoom, from the Ghanaian capital, Accra, hours before the opening of the exhibition that accompanies the album – a soft launch in paint and exuberance that came about, as things do with Eazi, by serendipitous happenstance. He had been mulling the idea of a multimedia project; an album perhaps, he wasn’t sure, but with art somehow. He was recording on the move, in studios, hotel rooms and lagoon-side houses between Nigeria, Ghana, Benin and Rwanda, with trips to the US and the UK too.

Being an A-lister, he’d initially gone about things the way A-listers do – with outside counsel. But speaking to galleries and curators wasn’t cutting it. Then, on a visit to Cotonou, he walked into the lobby of the Maison Rouge hotel and saw a painting by Patricorel. “I don’t know anything about modern art, I’m not cultured in art history. I didn’t know what style this was or where the artist was from. It was just this raw feeling and emotion that I cannot describe. I just knew that I had never seen love so beautifully described.”

From then on, he decided, if he saw an artist’s work and could relate it to something on the album, and if tracking them down and speaking with them yielded a similar level of connection, he’d commission them to make a piece.

The result is something like carnival: a restless, exhilarating cornucopia of sound and image and energy. On the album, longterm producers including E Kelly, Kel-P and Michaël Brun join forces with legends (Angélique Kidjo, Soweto Gospel Choir) and younger and rising stars (Tekno, Joeboy, Efya) alike, to cover a continent of styles and influences: afrobeats, afropop, hiplife, highlife, folklore, Ghanaian guitarist Joshua Nkansah’s virtuosic palmwine riffs, old-school sax and gospel keys.

In the show, which travels to London this month as one of the 1-54 art fair’s special projects, the Beninois painter Patricorel’s politically charged skeletal figuration is paired with South African Sinalo Ngcaba’s celebratory world-building, where, as she puts it, “a lot of different surreal Blackness lives”.

Eazi had found Ngcaba on Instagram. So much of the African art we see celebrated, to her mind, is serious in nature. She relished the license his commission gave her to just do her joyful thing and invite the listeners in. The resulting image, which accompanies the song Chop Life No Friend, is a portrait of Mr Eazi, hair in spikes as tall as a mountain, with lights, ribbon and a room of his own in place of facial features. She’d latched on to the standout lyric: “I’m continental / Sentimental / I’m monumental kpere [which Eazi tells me is a point of emphasis: ‘end of’; ‘full stop’].”

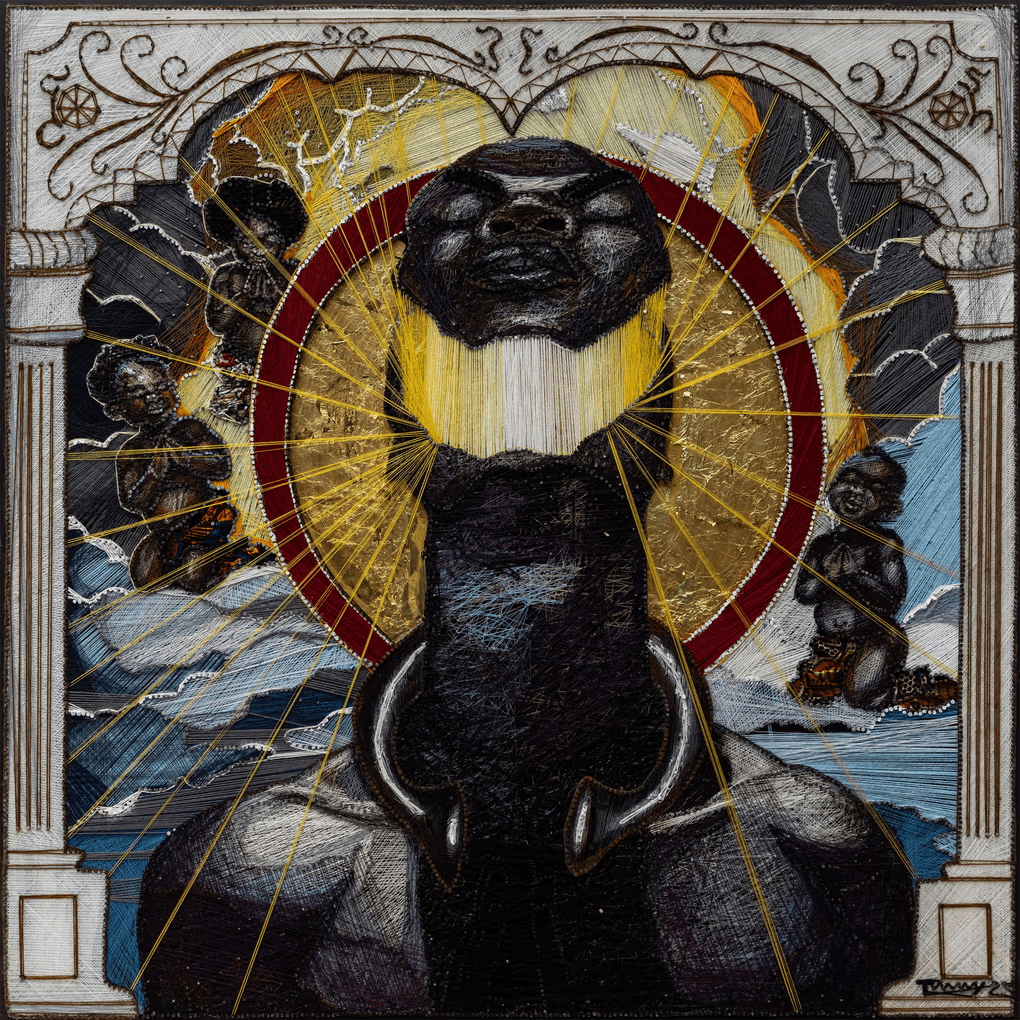

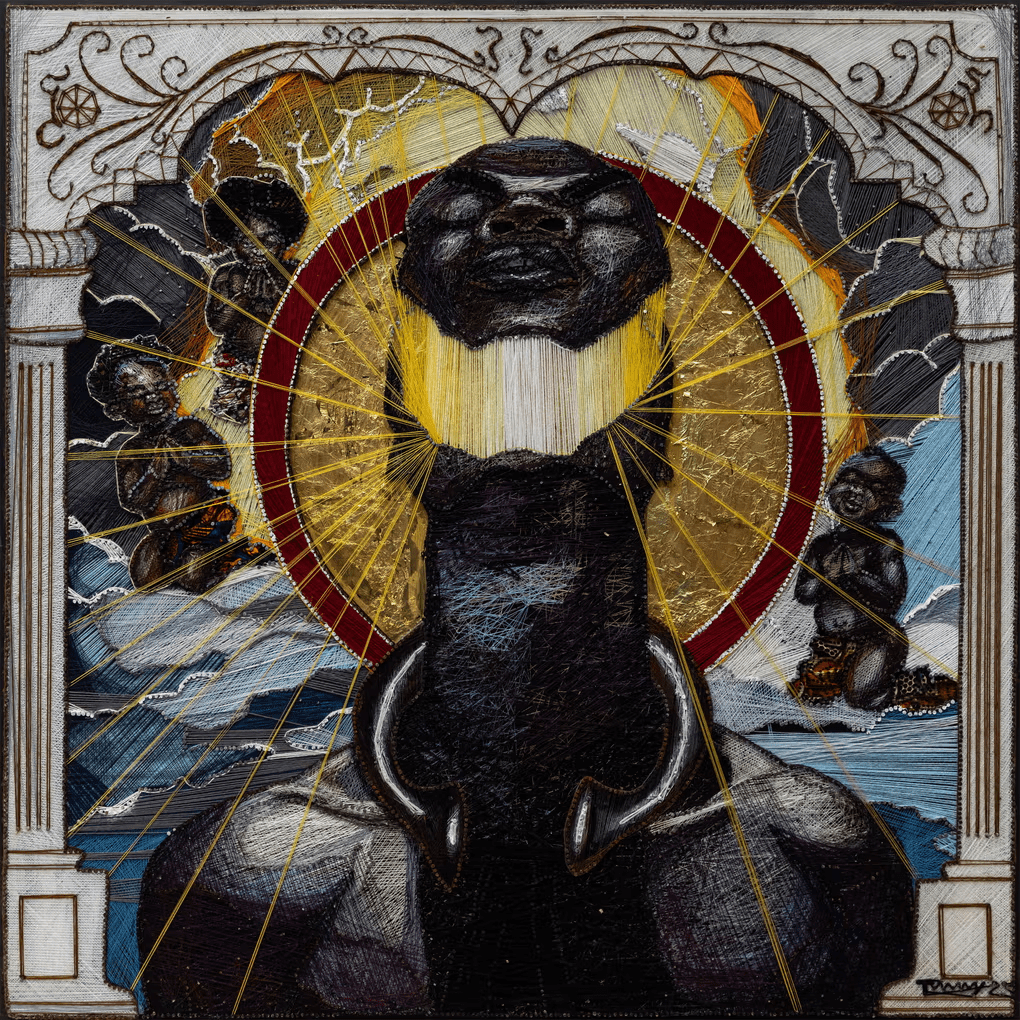

Nigerian painter Tammy Sinclair brings an equally expansive mirror image to the album’s opening prayer of a track, Olúwa Jọ. Black putti surround the head of a man whose eyes are closed and head lifted high, and from whom the sun is bursting.

Woven throughout the project is this unexpected combination of braggadocio and interiority, swagger and dream. In fact, Eazi says was taken aback by quite how deep the visual art led him to dig into his feelings. “It’s been the most therapeutic journey. It’s even enabled me to accept the idea of therapy.”

Talking with Sinclair became a moment of sharing, “about the pressures of fame, of having money, that sense of responsibility as a male Nigerian kid, as a first son – pressure that nobody even puts on you, that you put on yourself, and that I didn’t even realise I was expressing in that song.”

Conversations with the other artists ended up like this too: so emotional, so vulnerable, that at times he wanted to ask his assistant to get off the call. Does it feel brave then, to go ahead and release the project to the world? “I’ve never really seen it as bravery. But I’m not going to lie to you, there were so many times I almost shelved it. There’d be moments I’d think, like, nobody cares, people just want to party.”

Partying is how Oluwatosin Oluwole Ajibade first became Mr Eazi, back in the late 2000s. As a mechanical engineering major at Kwame Tech in Kumasi, Ghana, he was first Eazi Nakamura. (Obsessed with anime, he and his mates all added “Nakamura” to their nicknames: Peter Nakamura, Osi Nakamura, Sheun Nakamura. “They called us the Nakamura boys.” )

He had no particular intention to become a recording artist but did have an indomitable entrepreneurial streak. His mother and uncle would often think he was “away with the fairies”, he says. But he was never not paying attention. This often landed him in the right place at the right time, before he’d even formulated a plan. He once spent his tuition fees on a taxi because, as he has put it, “there was no Uber in Ghana back then”. He ended up running a car service as a side hustle.

The Guardian UK