Dialogue With Nigeria Akin Osuntokun

Next to Oduduwa, the eponymous ancestor of the Yoruba, the most significant monarch in Yoruba antiquity is Oranmiyan (purportedly Oduduwa’s son? grandson?). He was as elusive as he was ubiquitous. He holds the record, perhaps, in human history, of being a monarch, three times over, in three different world historic locations during his elastic lifetime, two of which are credited to him as the founder of the monarchical tradition, namely Benin and Oyo.

Oranmiyan, thereafter, returned to Ife to claim his original dynastic entitlement to the Oduduwa throne. Uniquely, it was at the request of the Edo people that he became the foundational monarch in Benin. Not surprisingly, his legendary footprints in Benin and Oyo fomented a millennial controversy that has lasted to this day. The harbinger of the latest recrudescence is newly installed Alaafin of Oyo, Oba Hakeem Owoade.

Having their ego bruised by the historical mentor-protege relationship between the Oranmiyan monarchy and the Oduduwa dynasty (from whom Oranmiyan was sourced), Edo nationalists had taken to reinventing the account of how Oranmiyan became the founder of the Benin kingdom.

“The Benin people believe that Oduduwa, called Prince Ekaladerhan, was the only son of the exiled King Ogiso Owodo. They believe that Ekaladerhan (or Oduduwa) exiled himself from Benin even before his father, King Ogiso Owodo was banished from Benin. Ekaladerhan or Oduduwa went to and founded Ile-Ife where he became King. After King Ogiso Owodo was deposed and banished, the Benin people went in search of the only son of the King, Prince Ekaladerhan (Oduduwa) with the aim of persuading him to return to Benin to succeed his banished father. Instead, Ekaladerhan (Oduduwa) sent his son, Prince Oranmiyan, to Benin.The Benin account has it that Oranmiyan reigned as Benin King from AD 1,170”

Lending scientific perspective to the understanding of the Oduduwa phenomenon “Archaeologists and historians estimate Oduduwa’s kingly existence to the Late Formative Period of Ife (800-1000CE), which aligns with indigenous Yoruba oral chronology”.

Oblivious of this record “Benin account has it that Oranmiyan reigned as Benin King from AD 1,170”. Between AD1000 and AD1170 is a gap of 170 years.

If this account is to be believed and thereby accommodate the theory that Oduduwa was the one who delegated Oranmiyan to Benin, it would mean that he (Oduduwa) lived for a minimum of 170 years. The inference is that Oranmiyan could not have been the son of Oduduwa whom the Edo claimed sent Oranmiyan as his proxy to rule Benin. The ruler of Ife (Ooni) who sent his son to Benin at the behest of the Benin solicitation has to be a father other than Oduduwa.

Let us now follow the peripatetic Oranmiyan to Oyo, his next port of call. In the historical account of the Britannica, “Oyo was established in the late 14th or early 15th century and grew into an empire that was dominant among the historical Yoruba states. Yoruba tradition and international scholarship had it that Oyo was founded by Oranmiyan, a son of Oduduwa, the deity who established the original Yoruba state of Ife centuries earlier”.

This account does not equally add up. In time perspective, it not only sets Oranmiyan farther away from his purported father-son relationship with Oduduwa, it also casts serious doubt on the Benin story that Oranmiyan’s reign in Benin ensued from AD 1,170. Between the 12th century and 14th century is a time lapse of 200 years. How feasible is it that Oranmiyan founded Oyo when he would have been above 200 years old? Credulity is further stretched by the report that the same personality went back from Oyo to Ife to mount the Ooni stool. In sum, Oranmiyan cannot plausibly be a single biological individual who ruled in Benin (allegedly c.1170), founded Oyo (14th–15th c.), and later became Ooni of Ife.

The legacy of the Oyo empire has been a bittersweet inheritance of the Yoruba, a legacy of glory and enduring tragedy. ‘At its apogee (1650–1750), it dominated most of the states between the Volta River in the west and the Niger River in the east…The empire maintained peace in the more open country of Northern Yoruba as well as on both sides of river Ogun among the egba and egbado, and west wards in Dahomey. It did not directly control Eastern Yoruba states of the more forested areas like Ife, Ekiti and Ilesha, Ijebu and Ondo but it had a working arrangement with them, based on the belief of a common origin at Ife for all the leading Yoruba Obas’ (Festus Ade Ajayi)

In the ebb and flow of Oyo empire history, the 19th century was the low tide. Her curve of glory was mostly on the ascendance up until the end of the reign of Alaafin abiodun in 1789. It was after his reign that the empire began to implode- defining the following one hundred years as an era of anomie and misanthrope. In the dated historical record of this era, Robin Law contends ‘the first problem which requires consideration is therefore the date of the coup d’état against the successor to Abiodun, Alaafin Aole with which the disintegration of the Oyo kingdom began”. He took us through a chronology of this period (1789-death of Abiodun: accession of Aole). (1796-coup détat against Aole, Afonja in revolt). (1817-Afonja allies with the Fulani and incites a revolt of the Hausa slaves). (1823/4- death of Afonja). (1831-1833-Fulani sack of Oyo) (1835/36-abandonment of Qyo lie). (1838-battle of Osogbo). It was at this war that the Yoruba army halted the Fulani incursion into Yorubaland with a decisive victory.

The ramifications of the potential failure of the Yoruba army at Osogbo are too dire to contemplate.There had been talks of the ambition of the custodians of the Sokoto Caliphate to dip the Koran in the Atlantic seaboard in Lagos.This was the euphemism for the projected conquest of Yoruba territory all the way to the Lagos coast. In the words of the late Premier of the Northern region, Sir Ahmadu Bello “These wars went on with varying success and at one time it appeared as though the ancient prophecy that the Fulanis would dip the holy Koran in the sea would come to pass”.

Beyond the theatre and relentless controversy is the opportunity for education in the informed knowledge of Yoruba history. By a consensus and aggregation of enlightened opinion, the Alaafin has exercised poor judgement in rushing to the media to declare hostilities on Ooni, giving him a “48 hours ultimatum” to reverse the conferment of a chieftaincy title.

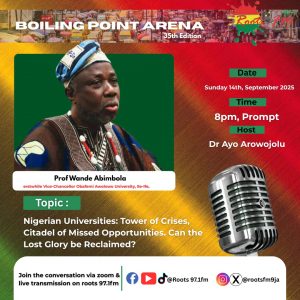

As a student of Ifa and Yoruba prehistory, I had more than a casual interest in the ascendance of Owoade to the Oyo throne. I was fascinated and gratified at the role of Professor Wande Abimbola/Ifa in the process of the final selection of the present Alaafin. The coincidence of Ifa instrumentality to the choice of the penultimate Alaafin (Lamidi Adeyemi) and his successor is quite striking. Dr Omololu olunloyo in his autobiography, recalled

“I had to visit ile ife when the trouble was too much , so I submitted the qualified names to Ooni Aderemi for help. Aderemi stood up and told me let me consult my ancestors. When Aderemi came back after two hours, he gave a clear answer to all our fears ! Adeyemi is the best of the pack, declared the Ooni, first of all he will live longer on the throne, secondly during his reign there will be peace and tranquility. I did not wait for a second, I thank Kabiyesi and left for Ibadan. The following Monday I call the press and announced Adeyemi as the next king”

Concerning Owoade, Professor Wande Abimbola commented “Ifa has chosen him; Ifa has picked him.. During the Ipebi, on three occasions, the Alaafin had good fortune to choose only igba oyin (honey-bearing calabash) each time he was asked to choose one from identical calabashes containing different contents. He chose igba oyin (honey) every time. This indicates that life under the new Alaafin will be sweet like honey”.

“When they reached the House of Ogun, kola nuts were cast seven times, and each time, positivity was announced. This is very pleasing. In the past, throughout Yorubaland, it was Ifa that chose kings. It was around the 1950s that things began to deteriorate for the Yoruba in terms of our culture and tradition. Up until the 1940s and 1930s, our heritage was still intact”.

It is difficult to reconcile the conduct of Owoade since he attained to the throne several months ago with the good tidings that Ifa had revealed, as elaborated above by Abimbola. Yet Ifa does not lie and I doubt that the diviner, a man of impeccable character and honour would have revealed what Ifa did not tell him. Sometimes, strange are the ways of Ifa, his wonders to perform. Could it be that Owoade is meant to pass through the less than dignifying clamorous phase as as a learning curve?

Primacy of Ife

On the primacy of Ife, I call to witness the consensus of opinion of four leading scholars, three of whom are not Nigerians (who have no dogs in the race of the Ife/Oyo supremacist contention). The three are Robin Horton, Robin Law and Andrew Apter). The fourth is Adeagbo Akinjogbin.

Andrew Apter asserted ‘From archaeologist evidence, it is revealed, we do know that by the fifteenth century, Ile Ife was the capital of a fairly large kingdom.This is borne out in the testimony provided by the Portuguese explorer and slave trader John Alfonso D’aveiro who, in 1485, recalled sighting a bronze head in Ife which can only be an indication that the bronze heads existed before the arrival of the Europeans on the coast of West Africa’.

Said Horton, the “outward diffusion of the Yoruba universalistic central tradition, as well as maintenance of uniformity throughout its area of diffusion, would have been further assured by the Ife-centric organisation of the Ifa divination cult, especially the uniformity of the corpus of Ifa divination poetry through the length and breadth of Yorubaland”.

He further noted ‘the post-fifteenth century Ife was the center of the Ifa divinational cult and as such, it exercised region-wide political influence of an “elder-statesman”. He was supported by the other members of the crew.’Be it Akinjogbin’s “enduring reverence of Ife as a “spiritual capital” and “father kingdom or Robin Law’s “beliefs, rites and gestures” of successor states which assert links with Ile-Ife as charters of dynastic legitimacy and locus of sacred kingship’

Stay ahead with the latest updates!

Join The Podium Media on WhatsApp for real-time news alerts, breaking stories, and exclusive content delivered straight to your phone. Don’t miss a headline — subscribe now!

Chat with Us on WhatsApp