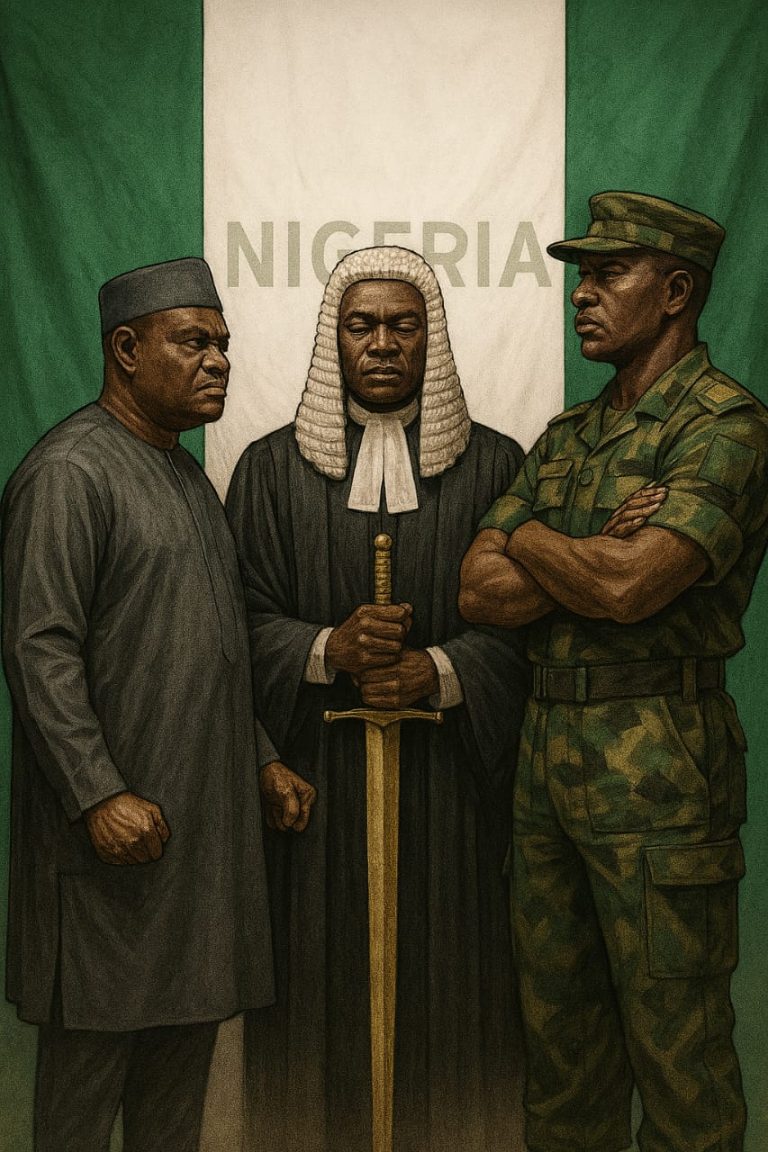

When a sitting minister confronts armed soldiers on public land, it ceases to be a mere administrative disagreement, it becomes a mirror reflecting Nigeria’s governance deficit. The November 11, 2025, standoff between the Minister of the Federal Capital Territory (FCT), Nyesom Wike, and military personnel reportedly from the Navy at Plot 1946, Gaduwa District, Abuja, transcends political spectacle. It reopens an enduring national debate. Where does civilian authority end, and where does military loyalty begin? Beneath the viral footage of verbal altercations lies a deeper question, who truly governs the Nigerian state, elected officials bound by the Constitution or a deeply entrenched uniformed elite operating beyond its reach? Recent developments, including a federal probe and public commentary from figures like Peter Obi, underscore how this episode lays bare Nigeria’s chronic institutional disorder.

Nigeria’s political evolution has long been haunted by its military legacy. Since the 1966 coup, every democratic era has coexisted uneasily with residual military influence embedded in governance, policy, and the economy. From the 2022 Magodo standoff between Governor Babajide Sanwo-Olu and police officers citing “orders from above,” to the 2003 abduction of Governor Chris Ngige under state authority, the pattern persists, a recurring triumph of the uniform over civil authority. The Abuja confrontation replayed this national drama, reinforcing the perception that the Constitution often bows before the barrel of a gun. In this system, elected leaders may hold office, but uniformed officers frequently hold the levers of power that truly matter.

At the heart of the conflict was a parcel of land allegedly linked to former Chief of Naval Staff, Vice Admiral Awwal Zubairu Gambo (rtd). Minister Wike a lawyer by training and known for his assertive governance style arrived at the disputed site with bulldozers and security operatives, declaring the occupation illegal. The soldiers, led by Navy Lt. Yerima, resisted, insisting they were guarding legitimate naval property under “orders from above.” The ensuing confrontation, captured on video, showed Wike visibly angered and threatening disciplinary action while the officer remained composed. No shots were fired, but the exchange symbolized the systemic erosion of civilian supremacy and the confusion of jurisdiction that blurs Nigeria’s institutional boundaries. Prior to the incident, Wike had revoked 30 hectares allegedly tied to senior military officers, including Gambo, as part of broader cancellations affecting 762 plots for non-payment. The Defence Headquarters has since ordered a probe, issuing cryptic statements on discipline and procedure.

Legally, there should be no ambiguity. Under the Land Use Act of 1978, all land in the Federal Capital Territory is vested in the President, with the FCT Minister acting as administrator on behalf of the federal government. However, decades of political interference and military encroachment have turned Abuja’s land administration into one of Nigeria’s most corruption-ridden systems. A 2012 Independent Corrupt Practices and Other Related Offences Commission (ICPC) review identified 13 “corruption red flags” within the FCT’s land management structure, including irregular allocations facilitated by top-ranking officials and retired officers. The Gaduwa controversy is therefore not just a property dispute, it is a reflection of elite impunity and institutional overlap that erodes Nigeria’s governance foundation. In truth, the clash exposes a culture of mutual overreach rather than one-sided military defiance.

That said, Wike’s conduct during the episode warrants scrutiny. His choice of words such as calling a commissioned officer “a fool” reflects an authoritarian impulse cloaked in civilian authority. Leadership is validated not by volume but by legitimacy, and the minister’s verbal aggression risks eroding the moral authority he claims to defend especially given his history of strongman tactics. This mirroring of military arrogance by political elites perpetuates Nigeria’s governance rot, where both khaki (military uniform) and agbada (civilian attire) compete not to uphold the law but to dominate it. True civilian supremacy must be grounded in civility, not intimidation, lest democracy devolve into another command structure.

Beyond the clash itself, the episode exposes Abuja’s murky land politics. Multiple allocations, revoked titles, and political interference have turned property ownership into a battlefield of privilege. According to recent Federal Capital Development Authority (FCDA) reports, over 4,794 properties are slated for takeover in 2025 due to unpaid ground rents, drawn from a list of 8,375 defaulters, many linked to politically connected developers or retired service chiefs. For ordinary citizens and investors, such volatility erodes confidence in property rights and undermines governance credibility. When ministers and soldiers publicly quarrel over government land, it signals a state losing its moral and administrative compass, deepened by the ethnic, economic, and institutional fractures often ignored in metropolitan discourse.

Nigeria’s broader security and governance architecture reflect the same accountability crisis. The National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) reports that between May 2023 and April 2024, over 51.9 million crime incidents occurred nationwide, with citizens paying an estimated ₦2.23 trillion in ransoms. Yet rather than reinforcing the rule of law, government continues to militarize civic life, from protests to urban demolitions. Surveys by the Centre for Democracy and Development (CDD) reveal that 73% of Nigerians view the police as corrupt, while 79% express little or no trust in the judiciary. When citizens fear their protectors more than the threats they face, governance shifts from protective to predatory.

The Abuja land confrontation is not merely about one minister or one plot, it is about the soul of Nigerian governance. The path forward lies not in more demolitions or force, but in rebuilding institutional discipline and restoring respect for the rule of law. The military must divest from private economic interests and respect civilian oversight, while politicians must abandon rule-by-decree temptations. Parliament should legislate clearer frameworks for military involvement in non-combat scenarios, and balanced narratives acknowledging both military service and civilian accountability must be encouraged. Ultimately, Nigeria’s democracy will only mature when both khaki and agbada recognize that public power is a trust, not a weapon. Until then, episodes like the Gaduwa clash remain vivid symptoms of a republic still torn between the Constitution and the gun.

Stay ahead with the latest updates!

Join The Podium Media on WhatsApp for real-time news alerts, breaking stories, and exclusive content delivered straight to your phone. Don’t miss a headline — subscribe now!

Chat with Us on WhatsApp