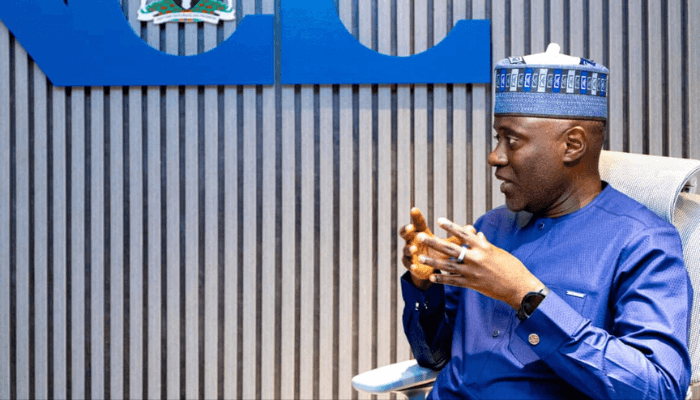

Dr Aminu Maida, Executive Vice Chairman/Chief Executive Officer of the Nigerian Communications Commission (NCC), does not doubt that the telecommunications industry in Nigeria will meet the full expectations of consumers and accelerate national economic development.

In this exclusive interview with Bashir Ibrahim Hassan, General Manager of BusinessDay for Abuja and northern Nigeria, Dr Maida, who obtained a PhD in Digital Signal Processing from the University of Bath and refers to himself as “somebody who has been exposed to a broad set of roles that has repeatedly put me in situations where reinvention was essential”, is humbly convinced that both his educational background and hands-on experience in the telecommunications and technology industry equip him to drive the sector. It is worth noting that this exclusive interview is Maida’s first since his assumption of duties.

“Before Nigeria gets there, a lot of things have to come together—we have to become an industrialised nation, then we have to become a knowledge-based nation, because telecoms is a highly standardised industry as well as highly competitive.”

Before your doctorate at the University of Bath, you had studied Information Systems Engineering for four years at Imperial College London. Could you put things in context?

Certainly. I chose Information Systems Engineering at Imperial in the late 1990s, right at another inflection point in the fusion of computing and electronics. Entire systems, CPU, memory, storage, radios, were moving onto single chips, hardware–software co-design was becoming the norm, and advances in digital signal processing were enabling software-defined radios. Globally, we were on the cusp of mobile broadband with 3G. Back home in Nigeria, I had just experienced the internet over dial-up landlines, and then you would see a few senior public & private sector executives carrying those 090 analogue NITEL phones. I wanted a programme that combined cutting-edge mobile technology with systems thinking. And Information Systems Engineering at Imperial delivered exactly that—four academically intense, rewarding years at the intersection of electronics, computing, and communications.

After Imperial, I returned to Nigeria for NYSC, then I got a scholarship back to the UK to pursue a PhD in Digital Signal Processing at the University of Bath. While studying for the PhD, I worked part-time as an enterprise software developer, which kept me grounded in practical delivery. On finishing, I had an offer from a global management consulting firm, but my PhD supervisor also introduced me to UbiquiSys, a UK telecoms OEM startup collaborating with the university. I initially declined and then decided to join. That path, moving between academia, software development, consulting opportunities, and an OEM, captures why I often say I’ve had a broad set of roles that repeatedly put me in situations where reinvention was essential. It has been a consistent theme in how I have prepared to contribute to this sector.

“We will strengthen measures against electronic fraud, cyberbullying, and impersonation, advance child online protection, and harden critical infrastructure against global cybersecurity threats.”

Now, at the time, UbiquiSys was trying to solve the problem of poor indoor mobile coverage, where the majority of phone calls are made. The company’s proposition was a customer-installed 3G base station, known as femtocells at the time but now falling under the broad category of small cells, which uses the customer’s home or business internet to connect to the core of the mobile operator’s network. I recall the CEO’s pitch to me. He said, “We are building a base station that can fit through your letterbox, does not require a technician to visit for installation and costs less than $100.” I asked where the product was, and then he showed me a medium-sized hard-shell suitcase with all sorts of circuit boards, chips and wires. At the time, it was a generation zero hardware, but he sold the vision to me, and I saw he had raised money from tier 1 venture capitalists and assembled a team of highly talented and accomplished individuals from the likes of Alcatel, Motorola, Nortel and Nokia, who were the giants of the telecoms OEM space at the time. So, I joined. I was staff number 22 and the only non-experienced graduate fresh out of university at the time; in fact, I was actually the only person of African descent. I saw it as an adventure, as I am naturally a curious person. I think initially I spent about four years there, and I was responsible for the intelligence algorithms in the products, specifically researching, testing and trialling the algorithms that enabled the product to work without the need for a technician to do any configuration: that is, you simply receive the product and plug it into your internet router, and your phone has full bars in your home or business. Over four years, we went from our generation zero suitcase to a product that could not just fit into the palm but also cost less than a hundred dollars and could auto-configure itself. That is, it did not require a technician to install. By the time I left UbiquiSys, we had deployed around 2 million units across the world. I was also a co-author of close to half of the patents the company held. I felt fulfilled as we had achieved the vision of a self-install 3G base station product. This was in 2006, and together with our other competitors, of which we had a few at the time, this was what started the commercial deployment of a category of base stations today known as small cells.

So, what people do not know is that I am one of the pioneers of small cell technology in the world and an author of some of the very early patents in that space.

I left UbiquiSys out of curiosity. I wanted to understand why the sales process with the mobile operators took months. We had sold to the mobile operators who, in turn, either sold or gave them to their customers for free or at a subsidised cost. I decided to go into the world of our customers.

I had just gotten married then; I consulted with my wife, and she said she would back me. So I leaped and joined EE—that is, the entity that emerged from the merger of Orange UK and T-Mobile UK. I joined as a consultant and drove their project to deploy 3G small cell technologies using Ubiquisys technology, in partnership with Nokia as the system integrator, under the brand name “Signal Box”. Around the same time, Vodafone UK was also deploying Alcatel-Lucent technology under the brand name “Sure Signal”. Vodafone deployed about 300,000 units in the UK, whereas in EE, we deployed about 250,000 units. Across Europe, it was the second- or third-largest deployment of 3G small cell technology at the time. The largest deployment by numbers was AT&T in America. They had over a million units of 3G small cells deployed by one of our competitors, IPAccess. UbiquiSys’s largest customer was SoftBank Japan, where they had close to a million units deployed.

For the AT&T 3G small cell deployment, Cisco had partnered with our competitor, IPAccess, and having seen the success of their AT&T engagement, they grew more interested in the technology. Cisco had this vision of adding a 3G/4G small cell module to their enterprise wifi access points, of which they had millions across the world. Now, Cisco is among the tech industry’s most acquisitive companies, frequently using deals as a core growth lever rather than only organic R&D. So, they did their assessments and eventually acquired UbiquiSys in 2013 for a modest fee of just under $400 million, which was a decent amount considering Europe was in the middle of a financial crisis.

Not all stories have a good ending. You may want to ask why we don’t see these miniature base stations in our homes. It is due to the emergence of alternative technologies such as “Voice over Wifi” and OTT apps such as WhatsApp and the like, which allow you to still use your mobile number as your identity. But nonetheless, small cells are central to the future of 4G/5G small cells—think mini mobile masts in buildings and lamp posts on busy streets. Most phone use is still indoors, and big outdoor towers cannot always deliver strong, fast, and reliable signals there. Small cells bring the network closer to people, boosting call quality and data speeds, and in 5G, they power private networks in places like factories and hospitals. In short, they are how we make modern mobile networks work well everywhere—not just near the big towers.

From Alan Carter, being your first boss then, what could you remember as a very important leadership lesson in terms of having a vision and following diligently to achieve that vision?

Alan Carter, who recruited me to UbiquiSys and whom I worked under throughout my time there, taught me that a vision only matters if it is backed by disciplined execution and relentless thoroughness. My PhD defence was my first real lesson in rigour, but Alan turned that rigour into a habit: be clear about the goal, ask the hard questions, test assumptions, and follow through to the last detail. That mentorship shaped how I lead today. At the NCC, and previously at NIBSS, some colleagues joke that they hesitate to bring things to me because I probe deeply and often spot gaps. I understand that, but as CEO, the buck stops with me—and Alan’s influence is why I insist on clarity, evidence, and accountability. He polished those instincts in me, and that grounding has been central to everything I have done since: hold a clear vision, then pursue it with focus, discipline, and an unflinching eye for detail.

So, back in Nigeria, where did you work, and what did you achieve in Nigeria?

Let me finish the UK chapter briefly. After Cisco acquired UbiquiSys, they asked me to return—this time as a Senior Solutions Architect in the new Small Cells Business Unit. I worked in the New Product Introduction team, essentially hand-holding early-adopter operators from concept to live deployment, often pre–general availability. It meant very close, trusted-advisor relationships and a number of successful launches that earned recognition inside Cisco. After a few years, I felt it was time for a new challenge and moved back to Nigeria.

I first joined Arca Payments as CTO around 2016. We had big ideas but quickly learnt that many of those ambitions depended on the efficiency and reliability of the national payments switch at NIBSS. When a leadership transition opened up at NIBSS, my colleagues at Arca Payments urged me to take on the role and help drive the change we all wanted to see.

I spent four years at NIBSS as Executive Director, Technology & Operations. I was responsible for technology strategy and the day-to-day running of operations and IT infrastructure. I came in a month after the new MD, Premier Oiwoh, resumed. We commissioned an independent external assessment of our infrastructure and built a roadmap to scale capacity to 50 million transactions per day, from under 2 million at the time. We launched a transformation of the organisation with new hardware and software platforms, modernised architecture and processes, and intensive staff upskilling.

That work was stress-tested almost immediately by COVID-19, when telecom and digital payment volumes spiked as the country shifted online, and again during the Naira redesign and cash shortages in January 2023. Those were tough periods, but the resilience we had started building, capacity, uptime, incident response, and operational discipline, helped the system cope. I am proud of the team and the foundations we laid to strengthen Nigeria’s digital payments infrastructure.

So, what would you say are your greatest professional successes, and what could you say, in addition, closely related to that, were those challenges you faced?

I would say being an early pioneer in small-cell technology is a standout achievement for me. Long before 5G made densification mainstream, we were proving that capacity would come from many small cells rather than just a few big towers—an approach that now underpins how modern networks globally meet exploding data demand. The challenge then was persuading operators and partners to back an unproven approach while tackling immature standards for small cells.

I am also proud of the transformation we drove at NIBSS. Between 2019 and 2022, NIBSS revenue grew at about 43% CAGR (Compound Annual Growth Rate) and transaction volumes at about 50% CAGR, reflecting stronger platforms, processes, and execution. The flip side was the scale of the lift: moving from less than 2 million transactions a day toward tens of millions, then absorbing shocks like COVID-19 and the Naira redesign—all amid the familiar headwinds of power, FX, and legacy constraints. These experiences reinforced the same lesson: match a clear vision with disciplined delivery, and keep building resilience for the unexpected.

What did you inherit upon assumption of office at NCC? What was handed over to you in terms of what was being done to achieve the constitutional mandate of this institution?

This is a big question, and the context matters. I assumed office just as the government made two bold macroeconomic reforms: the removal of fuel subsidy and the unification of FX rates. Necessary as they were, they immediately changed the operating economics of the whole economy, telecoms included. Now, I have to say I inherited a strong institution with a proud legacy: the NCC we know today is anchored on the Nigerian Communications Act 2003, itself a product of the National Telecommunications Policy 2000, which liberalised the sector. That policy is probably one of Nigeria’s recent success stories; it connected tens of millions and enabled digitisation across payments, health, education, and more. Without that liberalisation, if we were still under the NITEL monopoly, it is highly unlikely that we would have today’s level of connectivity.

At the same time, those macroeconomic shifts exposed structural weaknesses that the industry has had to and is now confronting. This is a business where, beyond salaries, almost every major input is imported, and of course, this means it is priced in foreign currency—radio equipment, software licences, spares, even many fibre and power components. Power is a particular stress point: Nigeria’s approximately 40,000 telecom sites must run 24/7, yet many are not on reliable grid power, so operators rely on generators. The sector is consuming about 40 million litres of diesel per month, and diesel moved from around ₦700 to over ₦1,000 per litre, almost doubling that line item. Meanwhile, the core hardware that runs global networks is produced mainly in China (that is, Huawei and ZTE), Sweden (that is, Ericsson), and Finland (that is, Nokia)—and all of that is paid for in FX. So you have rising local energy costs, FX exposure on almost every capex and opex line, and consumer price sensitivity—all at once.

What I also “inherited”, therefore, was the need to sharpen focus and direction: keep quality of service stable under cost shocks primarily through ensuring improved operational efficiencies, strengthening compliance and transparency, and investing in local skills so more of the value chain, software, integration, site power, and fibre build, can be done in Nigeria. But we also have to be realistic; in the near to medium term, Nigeria cannot start mass-manufacturing cutting-edge radio hardware, which requires a broader industrial base and standards ecosystem. But we can lay the foundations now, talent, R&D partnerships, local assembly/integration, and better operations, so that over time we move up the value chain. In short, I inherited a capable Commission and a sector that has delivered immense progress; our job now is to protect consumers, steady the network through macroeconomic volatility, and build the groundwork for long-term resilience and self-reliance.

What is your vision and plan for this institution?

First, credit to His Excellency President Bola Ahmed Tinubu (GCFR), whose clear belief in the digital economy is reflected in the team he has assembled—our minister and many agency heads come from the private sector and are empowered to deliver. My vision is for the NCC to lead Nigeria into the next phase of communications. In the last two decades, under the NCA 2003, the Commission successfully executed the National Telecommunications Policy of 2000, creating a competitive market that connected millions of Nigerians. The next phase goes beyond connectivity: the internet is now the platform for communications. The majority of us now communicate via chat, audio and video using apps that run on the internet, what we refer to as “Over The Top – OTT Apps”, and at the same time, the internet has become a platform for banking, commerce, education, entertainment—virtually everything. So it is no longer humans communicating with humans or machines; we now have machines needing to communicate with machines. In fact, your PoS machine is a good example of such.

We plan to create an enabling environment that will build a robust internet infrastructure that can carry today’s services and tomorrow’s—AI, IoT, augmented reality, and more. That means attracting investment in data centres, internet exchange points, and fibre-to-the-premises, alongside 4G/5G densification and smarter spectrum use. We will pair this with a transparent, pro-competitive, innovation-friendly regulatory environment, so private capital can scale fast.

Equally, we must protect people and the network. We will strengthen measures against electronic fraud, cyberbullying, and impersonation, advance child online protection, and harden critical infrastructure against global cybersecurity threats. In short, the NCC will champion a market that is investment-led, infrastructure-rich, innovation-ready, and safe for all users, so Nigeria’s digital economy can grow inclusively and sustainably.

Stay ahead with the latest updates!

Join The Podium Media on WhatsApp for real-time news alerts, breaking stories, and exclusive content delivered straight to your phone. Don’t miss a headline — subscribe now!

Chat with Us on WhatsApp