The developed nations of today were built on fair competition, where every citizen had a chance to thrive, not by government hand-picking a few to benefit from state-crafted policies.

As Feyi Fawehinmi, an author, noted in his review of Femi Otedola’s memoir “Making It Big”, in Nigeria, “you need not invent anything to become a billionaire. That is a waste of precious time.” This stands in stark contrast to wealth creation in other climes. In the United States, billionaires rose on the back of inventions, protected by patents.

“Many made fortunes based on their patents. Take Thomas Edison, the inventor of the phonograph and the light bulb and the founder of General Electric, still one of the world’s largest companies,” wrote Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson.

Nigeria, however, tells a different story. In the 1980s, when the government banned the importation of lighting products, Chief Beyioku Adebowale, a late industrialist, launched a venture to manufacture fluorescent lamps. Sir Michael Otedola invested N2 million in the enterprise. But the government soon undermined its own policy, granting import licences to Indian competitors. Sir Michael lost everything he invested in the invention of Adebowale.

The lesson is glaring: Nigeria offers almost no incentives for innovation. Instead, it prioritises licences, waivers and protection for the politically connected, enriching a few at the expense of the many.

Read also: Building cities of hope, not more states

The monopoly model

Monopoly enriches a select few while throwing the rest into poverty. The American government understood this long ago, which is why it established antitrust law, designed to protect both consumers and businesses from the stranglehold of monopolies and cartels. Giants such as John D. Rockefeller and J.P. Morgan lost their monopolies to the sword of antitrust legislation.

Nigeria, by contrast, entrenched monopoly through state backing. This gave a handful of businessmen unrivalled access to bank credit, while shutting out potential innovators.

Femi Otedola’s career is instructive. Government policy once gave him control of 93 percent of the diesel market, making him the darling of Nigerian banks. “When the going was good, Access Bank did everything to court me, practically begging to do business with me,” he recalls.

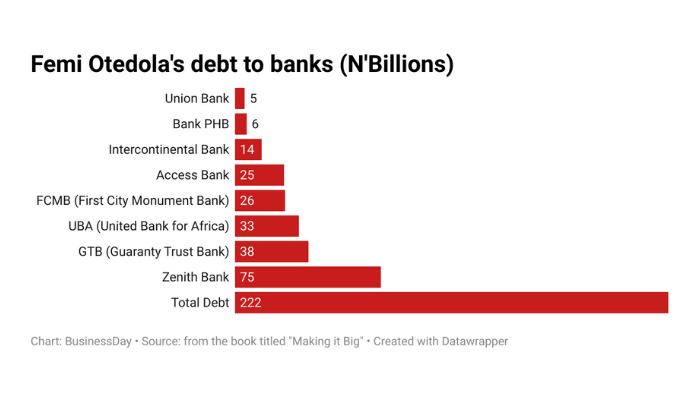

But when the 2008 financial crisis struck, oil prices collapsed and the naira depreciated; his $500 million diesel consignment was reduced in value to just $37. He became Nigeria’s largest debtor, owing around N222 billion, an amount so vast it nearly wrecked the nation’s financial sector.

The dangerous cost of crony lending

The figures reveal the fragility of Nigeria’s banking system. In 2010, Access Bank reported gross earnings of N91 billion, profit after tax of N11 billion, and total assets of N800 billion. Yet its exposure to Otedola alone was N25 billion, 14 percent of its net assets.

GTBank was no different. With assets of N1.2 trillion, it still had N38 billion tied up in Otedola, 18 percent of its net assets. As finance expert Abdulrauf Bello observed, “those were crazy exposures.”

Contrast this with the United States. During the nineteenth century, America experienced an extraordinary expansion of financial intermediation. By 1818, 338 banks held assets worth $160 million; by 1914, nearly 28,000 banks managed $27.3 billion. This intense competition meant inventors had easy access to affordable capital, fuelling industrialisation.

Nigeria, by contrast, channelled credit to a few state-backed monopolists rather than to innovators. Instead of financing the next Edison or Ford, Nigerian banks bet their balance sheets on a single oil trader’s gamble.

Read also: The price of privilege in a poor nation

Africa’s wider pattern of elite capture

Nigeria’s story is not unique. Across Africa, state-backed capitalism has produced billionaires, but not innovators.

As Tafi Mhaka observed in Al Jazeera, just four of Africa’s richest billionaires hold $57.4 billion, more wealth than half of the continent’s 750 million people combined. The top 5 percent of Africans now control nearly $4 trillion, while the remaining 95 percent subsist on scraps.

Nigeria and South Africa offer the clearest examples of this oligarchic dominance. In Nigeria, Aliko Dangote rose not through invention but through political proximity, securing cement monopolies and tax breaks that effectively stifled competition.

As Bello rightly observed, “I have great respect for Dangote, and I mean no disrespect. His success came in an oligopolistic market that eliminated consumer surplus. If his dominance had stemmed from genuine efficiency or strong value creation, as we see with companies like Google, Microsoft, or AWS, it would be a different story. To be frank, this kind of win is considered ‘low quality.’ His latest ventures may be different, but it is important to separate issues and attribute correctly.”

In South Africa, Black Economic Empowerment policies, designed to democratise wealth, instead entrenched a narrow class of politically connected elites, while unemployment and poverty soared.

The true cost of state-backed capitalism

Economists call this system crony capitalism, where political connections outweigh innovation, monopolies stifle growth, and wealth accumulation by a handful locks millions into poverty.

A Columbia University study cited by Mhaka found that fortunes amassed by politically connected oligarchs harm economic growth, while those of unconnected entrepreneurs have little negative effect.

This is the true cost of Africa’s state-backed monopolies: instead of fuelling broad prosperity through innovation and inclusive finance, as the United States once did, they entrench inequality, fragility and elite capture.

Until Nigeria, and Africa at large, creates a level playing field for innovators, its billionaires will remain monopolists, not inventors.

Stay ahead with the latest updates!

Join The Podium Media on WhatsApp for real-time news alerts, breaking stories, and exclusive content delivered straight to your phone. Don’t miss a headline — subscribe now!

Chat with Us on WhatsApp